Last updated: December 10, 2024

Article

Mooz (Moose)

Photo courtesy of Carl TerHaar

An exhibit about moose is upstairs in the Grand Portage National Monument Heritage Center beginning June 2024.

Icon of the North

The name for this iconic symbol of the North shore of Minnesota comes from the Anishinaabe word for the animal mooz (moose), which translates roughly to “twig-eater.” Among the Anishinaabe, who have revered and depended on this majestic animal for generations, it is a symbol of endurance and survival.

The largest member of the deer family in North America, Minnesota moose stand six feet tall at the shoulders and weigh 800-1300 pounds! That is about four to five times more than the more common whitetail deer. They run as fast as 35 miles per hour and swim up to 10 miles in one stretch. In fact, they are great swimmers, closing their nostrils for deep dives. Their impressive antlers reach up to five feet across and weigh as much as 60 pounds. Moose shed their antlers yearly in winter and immediately start growing them back.

The average moose eats 40-60 pounds of vegetation a day. Among moose favorites are maple, mountain ash, aspen, birch, cherry, and willow. Twigs, bark, leaves, and vegetation growing in lakes and ponds are all on their menu.

Moose, homebodies through most of their adulthood, stay within a 15 square mile range. They commonly live 15-25 years.

NPS Photo / N. Blake

Grand Portage's Waning Moose Population

Moose in Grand Portage long played a vital role for the Grand Portage people. Today, a prime focus of the Reservation Trust Lands Department is a commitment to the health and preservation of these awe-inspiring animals. In recent years, some in the community question the tribal use of moose as a resource.

In 2013, the state of Minnesota closed moose hunting season to non-tribal hunters to protect their declinimg population. In 2006, nearly 9,000 moose called Minnesota home, and by 2013 they numbered under 3,000. As of October of 2023, the number of moose estimated in Minnesota is 3,300 – thankfully a stable number for a decade.

Currently a smaller moose hunt is available for three Anishinaabe bands – Grand Portage, Fond du Lac, and Bois Fort. This is a limited harvest of only bulls to keep tradition alive. Today’s Minnesota moose population is stable but low.

The Effect of Climate Change

One explanation for the population decline is that over the last 25 years, shorter, warmer winters caused an increase in the winter ticks that were historically rare in the Grand Portage region. 2000 adult ticks can drink a half liter of blood, and some Minnesota moose have been known to carry 100,000 ticks!

Warmer winters also meant less snow in recent years, which allow more deer to move to this area, and more wolves to follow the deer. Wolves prey on moose calves as well as deer. Also, as more land is developed, many deer are pushed into traditional moose range. In addition to competition for forage, deer spread brain worm to moose. Deer carry brain worm without ill effects and shed it in their fecal pellets, picked up by snails and slugs. Moose and other hooved animals inadvertently ingest the gastropods while consuming vegetation.

Historic Impact of the Fur Trade

With many people to feed, moose provided an essential food source for the fur trade – a single moose supplies 400-700 pounds of meat. Their population at Grand Portage during this time averaged 1,000 or more. Moose harvesting during the early 1700s when French explorers first arrived, through the immense bustle of trade in the 1780s and 90s, decimated their numbers. European traders and Indigenous hunters and trappers amassed animals for profit and food. Journals note the lack of game meat as early as the 1760s. By the time the trade waned in the 1820s, the damage was done.

Formerly there were Moose & Deer- at this time not one is to be seen being literally extinct. Few are now seen- the scarcity of these Animals is greatly felt by the Indians. In Winter their sole dependance of subsistence is on rabbits and partridges.

-John Haldane, Fort William, Lake Superior, 1824

NPS Photo

Moose Hair Embroidery

Before beads became available through the fur trade, decoration came from local items. Porcupine quillwork is one example. In other areas of the north country moose and caribou hair embroidery decorated clothing and other items. This style of embroidery appears wherever moose and caribou are found — from the far north Athabaskans to the Northeastern woodlands.

The moose hair used for embroidery comes from the rump or neck of the moose, between the shoulders, where white hairs six to eight inches long are found. These are the longest on the moose. Fall and winter moose fur have the highest quality of hair for this use.

Three techniques using moose/caribou hair:

Standard Embroidery:

The hair is used as a thread through a base product, often leather or bark. The hair is individually stitched into a design.

False Embroidery:

Moose hair is dyed and wrapped over the weft thread so the pattern only shows on one side of the strap. It is called “false” since it is NOT applied to a woven item, but rather part of the weaving process.

Applied Embroidery or Couched Embroidery:

Several hairs are laid upon fabric or bark and stitched in place.

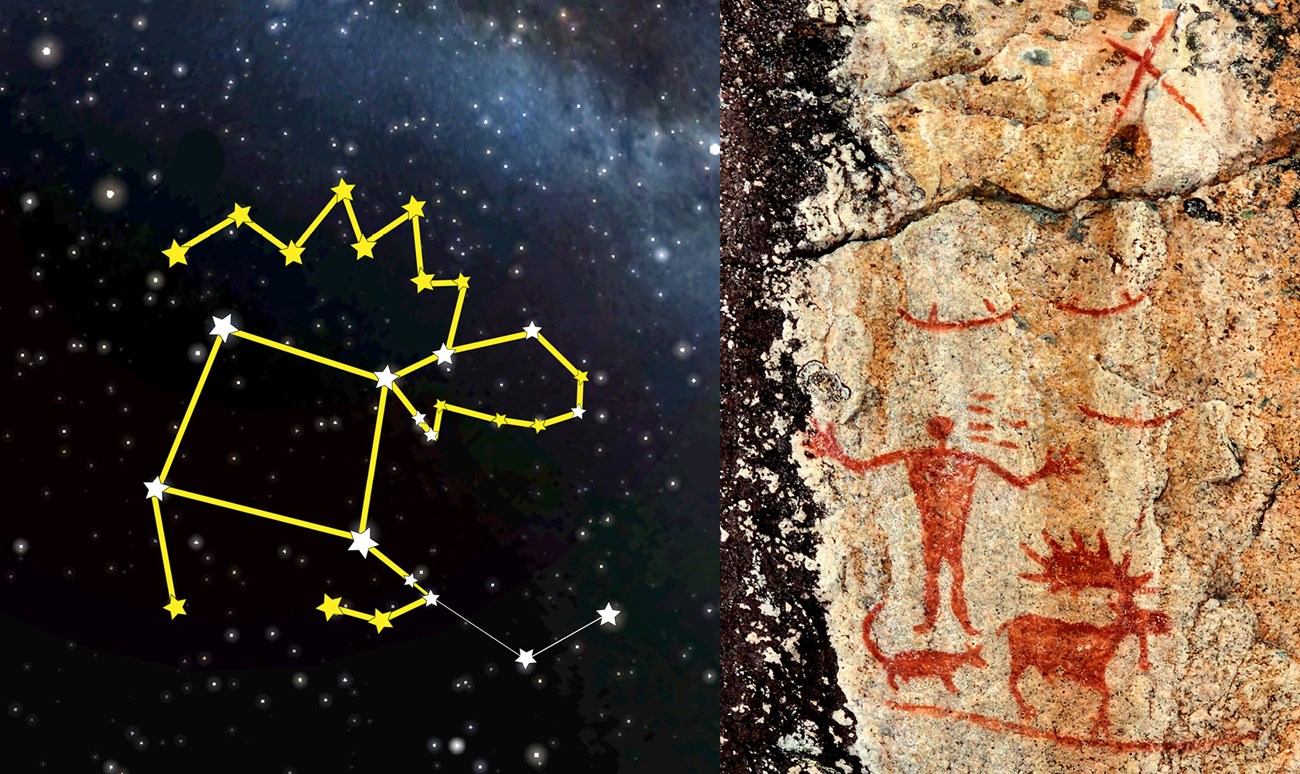

Hegman Lake pictograph depicting biboonikeonini (the Wintermaker), mishibizhii (Great Panther or Curly Tail), and mooz (moose).

NPS Graphic / G.M. Spoto, Photo courtesy of C. Neaton

Moose Constellation

Fall brings cooler weather and the time to hunt moose. This is also the time of year when the sky is clear, and the moose constellation makes its appearance. To the Anishinaabeg it is mooz, to others this is known as the constellation Pegasus.

Minnesota Anishinaabe artist Carl Gawboy is the first to propose that the constellation of the moose can also be seen at the pictographs on North Hegman Lake in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area. In addition to the moose constellation, Gawboy believes the man with the outstretched arms in the pictograph is the Anishinaabe biboonikeonini (Wintermaker - commonly known as Orion), and that the images are positioned perfectly towards viewing the constellations. To view the mooz constellation, simply face south and look up, the bright four stars above you form the main body of the moose. Fainter stars will detail the legs and head.

One lasting tradition in the moose hunt is to hang the moose’s beard or bell in a tree. This acknowledges the moose in the stars. The long connection of Anishinaabeg and mooz (moose) can be seen in pictographs in the border lakes between northern Minnesota Canada. It is here, rare ozaamanan mazinaajimowinan, (red ochre pictographs) remain. Other noted symbols include jiimaanan (canoes), ajijaakwag cranes, ma'iinganag (wolves), and bizhiw (lynx) on the rock face.

Survival

There is an old saying that says when there are no more moose, there will be no more Anishinaabeg. The North American word for this large member of the deer family, moose, comes from the Anishinaabe word mooz. Even though seeing one is top of every tourist list, the importance of this animal for humans dates back hundreds of years or more. Will environmental changes remove them from this landscape the way caribou moved north after the logging industry changed their habitat too much for them to survive here?