Last updated: May 11, 2022

Article

Monitoring a Singing Wilderness at Voyageurs

NPS photo/E. Burke

It’s true, and the things we listen for are intangible and as real as the birds who fill the days with song. It is those birds that we listen for each June as we conduct annual songbird surveys at 60 different points across the park.“I have discovered that I am not alone in my listening; that almost everyone is listening for something, that the search for places where the singing may be heard goes on everywhere.”

The National Park Service has monitored songbird populations at Voyageurs since 1995. More than 100 species of songbirds have been documented here, many of them, such as the Canada Jay and the White-throated Sparrow, representative of the conifer forests that extend from here to the Arctic. We recently analyzed the data collected during surveys from 2014 through 2018 to see how songbird populations are doing.

NPS and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service photos except Nashville Warbler © William H. Majoros/Wikimedia Commons

2014–2018

An average of 55 species heard at the survey points each year (range =51 to 59). The six most commonly heard species were Nashville Warbler, Ovenbird, Red-eyed Vireo, Red-breasted Nuthatch, White-throated Sparrow, and Blue Jay. Those same six species also had the highest population densities, each with >79 birds per square mile (mi2). The only statistically significant population trend was the Black-and-white Warbler, which declined at a rate of 3 birds/mi2/year over the five-year period.

NPS photos except Eastern Towhee (NCTC/B. Thompson) and Dickcissel (USFWS/S. Maslowski)

What Will the Future Sound Like?

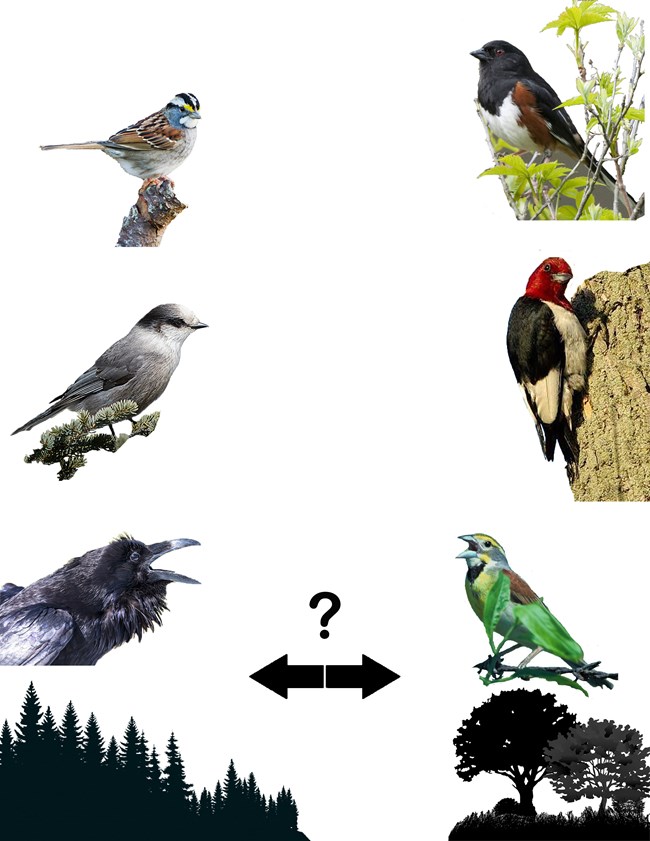

One study comparing bird population changes under two different climate scenarios predicted high turnover of species populations at Voyageurs by mid-century (2041–2070) if the nation continues on its current path of rising emissions1. The Red-breasted Nuthatch and the White-throated Sparrow, two of the most common species in the park today, are predicted to be extirpated from the park by mid-century, with the nuthatch maybe only appearing during the winter months. Extirpation is not extinction, but it does mean a bird species will no longer be found in a place where it has traditionally been. It will have to move elsewhere to find the proper climate or habitat for nesting and raising young.Meanwhile, the populations of birds more commonly found in open country and residential areas such as the Blue Jay, American Goldfinch, Baltimore Oriole, and Common Grackle are predicted to improve under either extreme climate scenario, while others like Brown-headed Cowbird, Dickcissel, Eastern Bluebird, and Eastern Meadowlark are predicted to move into or become more common in the area.

It’s important to note that a changing climate is only one part of this possible future. The habitat these birds depend on will have to shift as well. The Wood Thrush prefers a different kind of forest than the Swainson’s and Hermit Thrushes heard here now. And the Brown Thrasher prefers a drier, shrubbier landscape than is typically found in the park.

Birds will continue to fill the morning with song, but some of the future performers may be new.