Last updated: April 7, 2025

Article

Modernism at Risk

National Park Service

World Monuments Fund

David Bright: Good morning! I really appreciate everyone getting up and having breakfast and coming out so seemingly early for us New Yorkers actually. I was reminded at breakfast this morning that architecture in fact is really considered to be the most collaborative of the arts and in university settings I think today that’s certainly the case and hopefully you’ll feel by way of the remarks I’m going to make about our program that we have with the World Monuments Fund that some of that collaborative spirit is part of what we do. I’d also like to thank my colleagues from Knoll and from CI Select and everyone at World Monuments for coming this morning and some of our clients who are here as well.

This morning we’re going to talk about really what we’re doing with World Monuments Funds and I’m just going to talk a little of the objectives of my talk which is just to give you some background on World Monuments, describe the program we’re all involved with and talk about several case studies of preservation. This has been a great journey for all of us and I think, no one in this audience knows better that the places that mankind has built, really have defined our history and structures like this one in [inaudible 00:01:26], all tell a story of our past and they frame the accomplishments and the culture [inaudible 00:01:31] and the artistic aspirations of out world.

Places like this in Kyoto are testament to everything that we’ve done in terms of creativity and adapting the world’s diverse and multi faceted environment and really creating environments for our own use. What we have seen, all of us in this room, probably is that some places like this one in New Pakistan, are places that are so important to all of us that they take on a higher spiritual meaning in terms of the landscape that we all live in and others like this one take on almost a more iconic state in terms of the architectural landscape that they sit in.

All structures that we look at in our daily lives, as well as vernacular structures, religious structures, whether they’re part and parcel of a community, or part and parcel of a city, we really take on higher meanings for the people that interact with them and that really brings us to the topic that you all are much more versed in than I am, which is preservation. The preservation today, the field that you’re all involved in, I know demands more than the completion of high quality projects.

It’s incumbent on all of us in the room and all of who’s spent time in the preservation community to identify problems the heart of conservation challenges and address long term sustainability. One of the things that we’ve been so involved with with World Monument has been providing the stewardship and hopefully a little bit of the economic support at the local level for preservation.

I think everyone here is pretty familiar with World Monument so I’m going to go through this pretty quickly, but as you all know, World Monument is dedicated to saving the world’s most treasured environments and since 1965 has operated in more than 90 countries. The partnerships that World Monument has throughout the globe include projects in Asia, in North America, in Europe, as well as in South America.

World Monuments Fund

World Monuments Fund Watch List

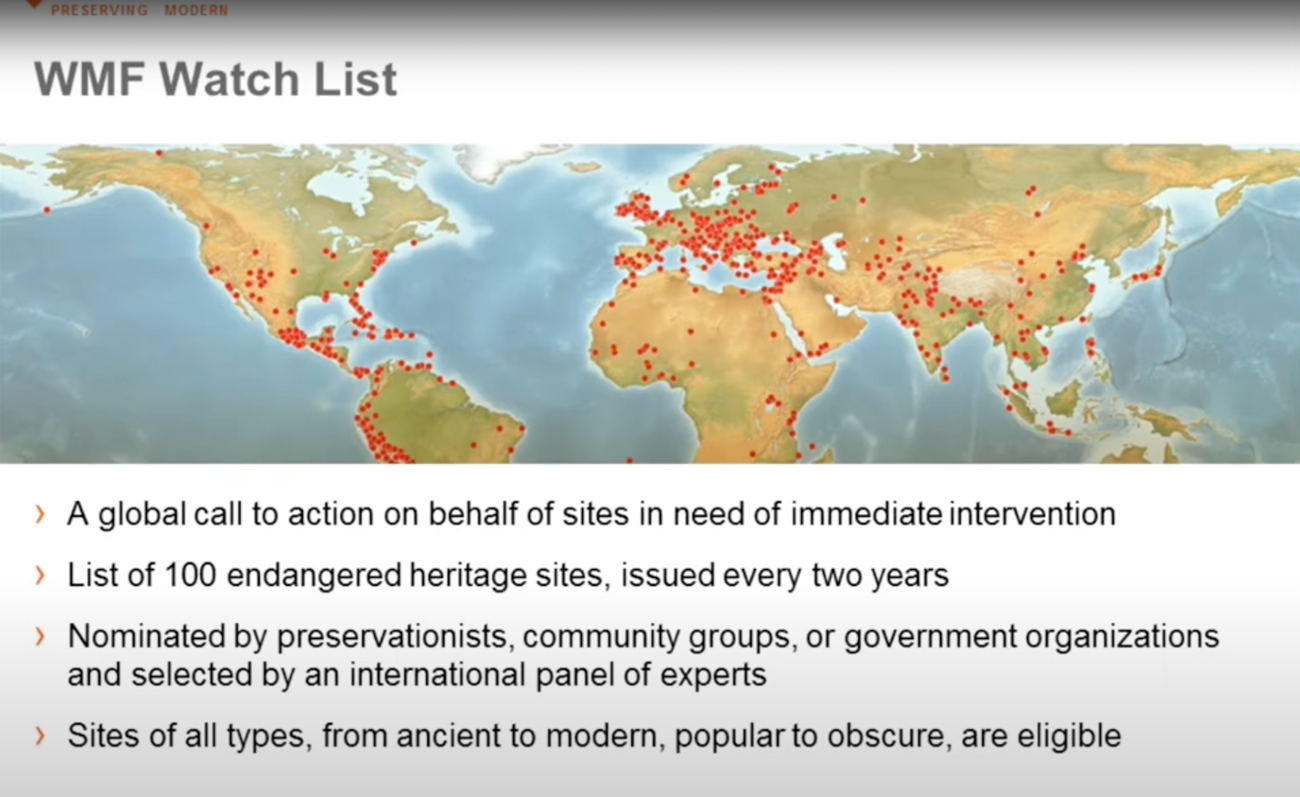

Many of you are probably familiar with the watch list which has been the signature advocacy program since 1996 and the list of a hundred different endangered heritage sites that are published every 2 years, really has served as a catalyst for students, for community groups and for professionals to become engaged in the preservation movement. The watch list has been one of the things that we’ve been most involved with at Knoll in terms of [plinging 00:04:10] to the foreground modern buildings that can be included with historic churches, with historic public building and with other sites globally.

Modernism as you probably know by way of this conference, has been one of the niche areas that hasn’t been much of a topic for World Monument’s types installations. World Monuments Fund, as you know, has been involved with signature projects like this one, when I do this talk in student groups, this is usually the quiz part of the program and you can grade yourselves as to whether or not you know the sites.

This one, any takers from the audience? Eris Island, thank you. This one from the classicist in the room? Pompeii, of course, Machu Picchu, and lastly the Great Wall of China. The real thing that we’ve been doing with World Monument is trying to integrate the Modernist vocabulary into several of their core programs. Those programs range from advocacy, raising awareness of the importance of heritage and preservation on the threats in this field, to education and training, training professionals in the preservation arena. Cultural legacy, which of course speaks to saving the cultural masterpieces and important cultural sites that have been subject to damage or destruction.

Lastly, capacity building which is really something, in terms of helping communities to recognize the value of sites that they have in their own geographies and putting together plans for those sites to be preserved. Disaster recovery which is something in the last several decades that we’ve been all too familiar with as the effects of global warming and other natural disasters have [impinished 00:06:08] on important sites.

WMF has several special initiatives, climate change, Iraq Cultural Heritage, a great program in European Fine Interiors, a program in Jewish Heritage, a program in sustainable tourism, and interestingly as of about 10 years ago, Modernism, which is why Knoll became involved with World Monuments Fund in setting up a program to preserve modern sites around the world. Everyone in this room, I think is very, very familiar with the need to preserve sites like the Huguenot House in the Czech Republic. The trials and tribulations of working with private individuals, with governments and with municipalities and private donors to create an environment that is friendly for preservation.

Projects like this one in the United States that you are all probably familiar with and if you haven’t visited [inaudible 00:07:04], I encourage you to do so because this site is really one that is … A very important in terms of the way climate has affected the physical space of the site and basically has been subject great public apathy in terms of getting the site fixed. Another site closer to home for me, which some of you may have visited I hope as children as I did, is the New York World’s Fair site.

Where there’s been really a great debate as to what the merit is of saving these wonderful structures designed by Philip Johnson and there really hasn’t been a correct adaptive reuse that has been identified to preserve the structures which continue to deteriorate. On the positive side, if you’ve ever had the opportunity to see this [inaudible 00:07:58] building in Barcelona.

This is a great example of communities coming together to actually revitalize the brutalist building under the World Monument’s umbrella and address the physical condition of the building, especially the fenestration of the building as it affected artwork and other delicate works of art that are housed in there all by Mirow and often as you can see here special exhibits by others.

That brings me to Modernism at risk which really what I’d like to spend the bulk of the time discussing with you, which is the program that we’ve founded with World Monument in July 2006 with the goal to preserve modern landmarks. It’s really in response to the growing threats to modern architecture that we launched the program with the WMF. It’s a new program, still very much in it’s nascence.

We work in 3 particular areas. We work in architectural advocacy, looking at building that face demolition and thinking how they can be preserved. We work in the conservation arena, looking at initiatives for selected conservation projects that really can impact the communities where the buildings are housed. Most interestingly and probably closest to my heart is the public awareness initiatives that we do with students and university communities to promote the Modernist aesthetic, not only in terms of it’s historical context, but also in terms of the role of Modernism in the communities where these buildings exist.

I encourage you all to take a look at the Modernism at Risk website if you have not done so and you can see some of the great projects that WMF is working on in general and also some of the projects that we’ve worked in. The one thing that I wanted to orient you to and those of you who are educators in the room, is the exhibition that we have circulating on the program. The Exhibition Modernism at Risk solutions for saving modern landmarks, was designed to bring a greater awareness to the entire subject of preserving modern buildings and extending the lives of these buildings.

The show opened originally at the Florida College of Design a Construction and Planning and I said it’s circulating throughout universities in the United States and actually has been viewed abroad as well. What I love about the exhibition is that it consists of 21 photographs by the noted photographer Andrew Moore and those of you who are interested in a less studied view of architectural photography, I encourage you to explore Andrew’s work on your own time.

Andrew made his mark by photographing decaying sites in Cuba about 20 years ago when access to many of these sites was much more limited than it is today and will be in the years ahead thanks to the initiatives of our president. His monograph on Cuban architecture including many Modernist sites is really fantastic. There are case studies presented as part of the exhibition and what we have focused on in the exhibition and I’m going to into some of the cases in detail in a moment, is really mainstream modern.

We’ve been most interested at World Monuments and Knoll in focusing on buildings that have public access. I mean there’s been a great deal of attention some of us were talking earlier about initiatives in Palm Springs to restore residential building in the Modern movement, but our initiative has focused on buildings, public access, civic buildings, educational buildings, even looking at religious buildings that have been re-purposed for public use.

What I’d like to do and this is probably of interest to most of you in the audience, is take a look at some of these projects and talk about them in terms of their historical context and some of the preservation initiatives that we’ve undertaken. The first one is very near and dear to anyone who’s interested in the history of architecture and the history of Modernism in general.

It’s the Grosse Point Public Library and as you can see the architect is Marcel Breuer. Anyone from Michigan here who has visited the Grosse Point Public Library? It’s an amazing building and Breuer as you all know, is recognized as a pivotal leader in the Modern Movement in the 20’s and 30’s of course, as master of the Baha’i School. I included this photograph in this talk because I think it captures so much about what Breuer is about, what Breuer’s journey to the United States was so much about, and what he stood for, not only in the context of architecture, but also as you can see in furniture design.

This photograph is by John Naar who is another photographer who do a lot of portraiture of artists and designers in the late 50’s and early 60’s. Believe it or not, he’s still alive. John is 95, 96 years old now and still working as a photographer and most recently he did a talk on, what you can see on our Knoll website, about his collaborations with Massimo Vignelli, the noted graphic designer who is so important in defining Modernist aesthetics in the United States and I would encourage you to take a look at his talk.

He’s a great person and you can see from this photograph, he’s a great photographer in terms of capturing the emotion that Breuer brings on to the forth round of the photograph with his espresso cup. The layer of the objects from … in the middle ground, his beautiful shades lounge, his classic chair and the architectural elements that he’s so well known for in the United States. This was photographed at his new Cayaman, Connecticut residence.

Here’s a vintage photograph of Breuer’s Baha’i Institution, which he was forced to leave and immigrate to the United States. The really cool thing about the Grosse Point Public Library is that it was celebrated so widely locally in the Michigan community. This was Breuer’s first public building in the United States, when he came to our country. You can see how the library and the building in these news clips really talk and put the library in the context of the Detroit lifestyle.

Which of course you can never a photograph in Detroit without an automobile for a news paper. I’m sure that was a coveted placement for … Does anyone know what car that is? I’ve never really thought about it, but the coveted placement for the manufacturer to be seen in the context of that building as a background. As I said it, Grosse Point was his first public commission, it was design soon after he established his own firm. It really defined a moment of time when editors like Henry Luce at Time Magazine, tried to create an atmosphere of the American architectural scene as becoming a dominant course in world artistic affairs.

Here’s the façade captured by Andrew at just about this time of year actually and you can see that it’s a very, very simple, simple building from the streets gate. I think the most interesting part of the facade to many people is the topography and the wonderful way in which Breuer made Grosse Point Public Library almost into an architectural statement on the façade of the building. Here’s another view, some what more animated, of the façade. All photographs, of course, by Andrew, showing the relationship of the fenestration of the building to a little set back streets cape park and allowing people from the street to enter the library from the street and become involved in the day to day affairs of the library.

I’m going to read to you a brief quote from a 1954 public lecture by Hawkins [inaudible 00:17:32]. Hawkins’ family commissioned the library and intended the library to become a community center, which was a very, very forward thinking view of what a library what should be in context of American life in the post war era. [Either 00:17:52] 2 libraries were probably were dedicated to scholars and really not as open to the community. I need you from his opening speech, “The ideas implanting of many people went into the realization of this building, but it’s final form as we see it today, is the creation of the architect Marcel Breuer. He visualized the building, not as merely a repository of books, but as a social, cultural, and civic crystallization point.”

Things that I think we see so often today in terms of the way of people are thinking about new buildings, whether they’re health care, commercial, educational or governmental, so I particularly like what he had to say. Unfortunately, over the 5 decades the library was really was never loved by the community and on this view of the façade, you can probably see why. I mean, it doesn’t really have the welcoming view that it did on the street side. That said, there were very few minor alterations made to the building and very few upgrades and over time, the building did deteriorate in many ways.

It was encroached on by a parking lot, as only Detroit could do. It became, sort of an island within this streets cape area in Detroit. The great thing about the library is the interior and as you can see, on the construction of the building, really celebrated from the street. The Kandinsky tapestry that you see in the background is still there today, [inaudible 00:19:48] was moved in terms of the Art program, you’ll see a couple of other pieces of art in a moment.

It’s really been a testament to just a few people to try to preserve the library and preserve Breuer’s legacy as it existed early on. Here’s you can actually the streetscape with the [inaudible 00:20:10] in the foreground which is very dramatic. The furniture is not original to the building. Interestingly enough the furniture was originally done by our firm, but it was dispersed many decades ago. You can see that the building has this uncomfortable relationship with these colonial revival buildings on the other side of the street.

There’s a nod to the street, I think that the residents of this community at the time were much more comfortable with the colonial revival architecture on the other side of the street. These are a few of the schemes that several of the architects who compete, who provided input to the library developed in order to add on to the structure and preserve the structure and it’s current form. The community really wanted to tear down the building and everything that we did with World Monument in terms of building community support was geared towards saving the building, providing alternatives to the building and creating some additions to the building that you can see here, which have yet to be realized.

Not that this is a very, very successful case study in terms of the ability of several different types of community groups, a national or a worldwide organization like World Monuments and private individuals to preserve the legacy of the Breuer building, which, as I said, is important in the pantheon of American architecture being Breuer’s first building in the United States.

River View High School is probably very familiar to many of you and it’s not a happiest story as you can see on the slide, this school was demolished in 2009. It is a signature building of Paul Rudolf, who is best known for this whole Sarasota Modern School of Architecture and interestingly Rudolph pioneered so many of the, not only architectural idioms, but the structural idioms that we’re so familiar today in that part of the country.

You can see here from the façade how Rudolf really was most sensitive to the relationship of the building to the landscape court and how he used in so many ways passive means of cooling and lighting the building.

Which in these photograph are very well illustrated despite the decay that you see in terms of the canvas screens and some of the steel beam work as well, but that was the signature element of this building in terms of it’s contribution to the history of design and unfortunately the community did not agree with those who wanted to preserve the building.

The community was dead said on building a new high school and demolishing the building to what is today create a football field. The whole tension in the community as to what the right purpose is of academics/sports setting was hotly debated and the little discussion was given to the innovations like the concrete sunshades that I showed in the prior slide to the trance in windows to the open roof monitors to the whole idea of passively cooling an interior features that today, I think those of us in the room probably value as part of the sustainability movement, but in the context of educating high school students in today’s world, we’re not really seem to be as relevant.

Here you can see the school as it’s being built from the site and here are just a couple of the interiors which certain members of the community sought to preserve as part of a 2 year campaign to create either an alternate use for the building or to actually re-purpose the building for contemporary education. What I love about Andrew’s photographs once again, is how they capture in a very close and upfront way the spirit of the space and the actual function of the space.

This is actually a part of the building which was preserved, okay? It’s not really the signature area of the building, it’s now being used as a community arts center. What’s great about this is you get a sense of Rudolph’s design, you get a sense of his use of the stairwell, as architectural elements on the exterior and you can see in the background too, some of the breeze way elements are still preserved as well, but it’s not the signature piece of the building.

Interestingly for those who you are following modern preservation in the northeast, there’s a Rudolf building which is hotly debated right now in Orange County which is about 2 hours north of New York City that Frank is smiling because he’s been involved in efforts to preserve for that building and I guess we’re all waiting the outcome to see what happens there.

That building is probably more keen to Rudolph’s work at Yale at the Architecture School in terms of it’s brutalist style and the community had various debates as to what the fate of the municipal building should be. I would encourage you all to take a look at what’s going there. A couple more photographs of the interiors as they looked during the debate which you can imagine you’re a parent of an adolescent, which side of the argument you probably would have fallen on.

This is another great story in terms of the work we’ve been doing with World Monuments. The Kent Memorial Library is in Suffield, Connecticut and as you can see from the slide, it was designed by Warren Platner. This is the only building that Warren Platner completed on a free standing basis. Of course those of you in the room who are familiar with Knoll know that Warren Platner also designed an iconic furniture, sweet for us which is recently had a considerable revival in terms of it’s popularity.

This building was completed in 1972 and it compliments and contrasts very much the neighboring buildings on a very picturesque New England town green. You can see here how the building sits back from the road, it’s actually opposite the historic library that the community built in the 19th century which was traded to a private school called Suffield Academy and made part of the Suffial campus. Now it’s sort of [inaudible 00:28:02] modern, the scale, the [inaudible 00:28:05] roofs, echo many of the colonial era idioms of that place and recall pretty much what it’s meant to be in the context of a New England village.

World Monuments Fund

Case Studies

The reason I love this good old mini case study on preservation of modern is that, I received a telephone call from an accountant in town who clearly was looking at the town budget. The town was interested in demolishing this building, putting up a library, pretty much the same scenario as Grosse Point and he said he found the name of our program online and that he and his kids wanted to save the building. I was like “Okay, well, that sounds like a great idea.”

They literally put together a grass root, bumper sticker campaign, selling lemonade, everything you’d expect in a small New England town right out of the Norman Rockwell playbook and actually succeeded in convincing the town council to save the building. I’m going to read to you a quote from the architect Richard Monday, who is a principal of Newman Architects in New Haven and he’s a real admirer of the building and Platner’s work in general.

“Very few libraries treat the book or the reader with such honor and care and with this much attention to act to the act of reading. Each of it’s public space was conceived, like the library in the house, as a warm and intimate space that welcomes the individual.” If you can [inaudible 00:29:43] that to most of the work that Platner did, those of you who are familiar with the Ford Foundation or even his restaurant at Windows on the World, he was taking a different tack and exploring a very different side of his view of design.

He is mainly, as I said, an interior designer, working in New York City. Did a few projects in New Haven as well, but it’s a very different approach, as I said, then the Ford Foundation offices which he designed or many of the other public spaces and here you can see iconic sweet of furniture for Knoll. It’s a very complete set of table and chairs done in the wire idiom, the next step if you will to some of the work that we did with Harry Bertoia, an interpretation of that.

I mean this contemplate of [normants 00:30:59] to me are so reminiscent of Kyoto Temple … To me there’s always been a very much a Japanese quality to the spaces that Platner created with these garden courts. Here you can see how Andrew chose to memorialize in a way a moment in time in library life when archives were created in boxes and people typed folder tabs with electric blue IBM type writers.

I should say that, although this talk is really about the buildings, but you know Andrew … This room was exact … He did not prop this room, he did not prop any of the interiors that I showed you. He just shot them the way they were. The building has a remarkable charisma on a sunny day. I’m very pleased that the [inaudible 00:32:04] family initiated this with us and World Monument.

I noted that we focus on public spaces principally, I thought that it would b interesting to this group to learn a little about what we did with the Goodyear House. This initiative really predates most of our work with World Monuments, and Frank can correct me on any of my historical plunders in terms of this particular project. The Goodyear House was built by Conger Goodyear, he’s the first curator of Architecture and Design at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. You can see here, it was really built in the style of a sprawling country house, of course, the [inaudible 00:32:59] are very, very obvious in terms of what Stone was thinking about. The house was meant to really sit in the countryside and to be seen from this dramatic, public drive set on at Knoll.

Overtime, those of you who are familiar with this part of Long Island know that it’s been densified, it’s been really subject to a great deal of suburban development and the house came on the market, it was debated as to how to best handle the property and deal with the property which had been actually been given to a local community college. Which wanted to monetize the property in terms of it’s educational purposes. This photograph which I’ve put in recently to this slide deck, shows this wonderful Noguchi table in the foreground, which actually I believe resurfaced at an auction a couple of months ago, in a Modern auction.

You can see Noguchi’s work is so well suited to the interior of this house and creates this great dramatic effect of sculpture from the indoor and sculpture from the outdoor, but it’s a one off table and of course is some what precursor to a table that I call brand X sells today at one of our competitors.

Here you can see the house as it was restored by the owner who purchased the house under our complicated set of covenants with World Monuments and the community college to actually preserve the building. You’re probably all saying “what does that [inaudible 00:35:04] have to do with the context of the house?” And the answer is I really have no idea (laughter), but he felt that it was an appropriate sculptural entry way, but it has nothing to do with the [inaudible 00:35:19] of the house.

I’m just going to read to you a brief quote by Stone which I think, sort of speaks to some of his thoughts on the house. He’s talking as a student and he says “Changes in architecture were gathering momentum, [inaudible 00:35:39] first books were being published in the nearby [inaudible 00:35:42] the Baha’i House was founded. All heralding the arrival of the new machine age. Those ideas were contagious and we students spent our time redesigning the United States on Marvel Top Café tables.

I think that’s great that he actually realized this design in Long Island. You can see how the house has been meticulously restored, it really had fallen into disrepair. All of the fenestration, all of the steel, all of the cement in the court and the relationships between the garden and the house have been maintained very well. Although, if you were to visit the site today, it’s basically surrounded by what some people would call McMansions unfortunately.

Here you can see a view after the trees were pruned off the terraces, once again the courtyard where the owner at the time installed a contemporary sculpture, but he really made a good faith effort and unfortunately was forced to sell the house again to another buyer. The second buyer now is working on the house, to restore it and I think there’s hope that it’ll be open to the public eventually.

The next project that I want to talk to you about is a trade school in Germany, it was designed by Hannes Meyer. It’s the recipient of the first World Monuments prize for the Preservation of Architecture. I’m going to go through these slides pretty quickly, these are all prize winners from the past few years. You can see here the original plan of the school, you can see here how the school was restored in this very exuberant way with the garden court.

This was really a monumental undertaking in terms of the restoration mainly publicly funded and the restoration of this great breeze way that connected all the buildings took years and years and you can see once again, how Hannes Meyer was most interested in creating a sense of and connection to the landscape, but preserving what really was the key function of the school which was an academic community.

The restoration here, involved color analysis of all of the original Abajos colors which were coded by buildings, particularly for the dormitory blocks. The research was very interesting in terms of determining the different color pallet and you can see how it was realized here in the dormitory block as well. Here are the restoration architects celebrating their work. The space is in no way looked as they did when the building was originally constructed, you can see here how it was originally and then this historic restoration which almost got [inaudible 00:38:54] up to a point that it never had originally.

Here … This is the … Really one of my favorite, this is the stairwell and breeze way as it existed about 10 years ago. The magic of the design was restored, particularly these pivot windows, which were just an engineering feed in terms of the [inaudible 00:39:20] construction. This is the type of work that World Monuments really loves to take on in concert with those around the world. I’m assuming it’s the work that really turns on most of the people in this room as well because it’s a meticulous engineering and design work and you can see how these windows were originally in the same way Rudolph used his screening devices in Florida. How Hannes Meyer used a similar construction here in Germany. I see that my time is going quickly.

Speaker 2: [inaudible 00:39:57] good?

David Bright: I’m good. I want to give you a sense too of some of our other prize winners and I should say that the prize is given every other year. The jury is independent, there are no Knoll associated with the jury. The jury is chaired by Barry Bergdoll, who’s a professor of Art and Architecture at Columbia University and he puts together a panel of individuals on a rotating basis to solicit projects and to debate the merits of the projects.

This one is in another amazing government funded project in the Netherlands. You can see just as in the German project, there was a broad campus plan, it was originally designed not as a school, but as a sanitarium for people suffered from Tuberculosis. This was the building when the team took it over and re-conceived that the building could be re-purposed from a health care facility for a disease that has been virtually eradicated to a community health center.

The state of disrepair of this building will be daunting for anyone, I’m sure. Over a period of a decade plus, you can see how the building has been restored, how the fenestration, how the steel, how the cement has all been put in a contemporary context and contrast this tower with it’s beautiful glass stairwell to what you saw originally.

Might as well started from scratch, but it’s the tenacity of the architectural team and the research that they undertook that really lead the jury to award the Modernism prize during this year to this project.

The third prize winner that I want to just run you through is a bit of a sleeper. Probably my favorite project that World Monuments has identified for recognition. It’s a school that was designed in the mid 50’s by a Japanese national and it sits on a lovely site in a rural area of Japan and immediately, hopefully based on many of the images that you’ve seen in this slide deck, you can see the similarities and the parallels between some of the Baha’i house buildings and the American modern buildings that I’ve shared in terms of the way it hugs the river bank and the way that the exterior stairwells are used to connect people from the outside to the inside. It’s not a school that would be ever built today.

The community was extremely, extremely proud that this building existed and very much a western/Japanese idiom in the community and didn’t want to see the building destroyed and actually put together a plan to bring it up to code to meet the educational standards of the Japanese National System. You can see the building here restored by the river bank. What I love most about this building is the interiors in the way, sort of the craft activity of local artisans is filtered in with some of the more structural and technical initiatives of the Modernist engineers and architects.

What better place to go school, right? I mean compared to some of the buildings that we see in the United States being built today for elementary education, this is a real [inaudible 00:44:06] and deserved the jury’s recognition.

The last project that I want to share with you is the most recent prize that was awarded this past fall. It’s the very well known building, when I showed the color slides, you all recognized it. It’s the library that Aalto designed in what was then Finland, but is now Russia. The project represents a real cultural collaboration between these 2 countries in a contemporary way in a world where collaboration on a geo-political front has not been as smooth.

I feel that the jury picked this building to emphasize that architecture and design can live above some of the other issues that we face in the contemporary world and conserve as a symbol as I said earlier of being the most collaborative of all the arts. Here you can see the library restored, recognized these wonderful skylights from your Art101 books hopefully. The way in which the library was revealed on the second level to visitors from the entry court at the foot of these stairs.

This was a real meticulous, once again, multi-year project, principally funded by the Russians in a time … politically when probably they were focusing on many other areas of concern and then of course you can see how wonderful the stools actually work in the building. The [inaudible 00:45:54] ceiling is [inaudible 00:45:58] of course of Modernist vocabulary and one in which the building is probably best known.

Hopefully, I’ve given you a sense not only what we’ve done in advocacy, also what we’ve done in terms of recognition and I would welcome any discussion or questions that anyone may have about some of the work that we’re doing today. I would also be happy to participate in the questions.

Any comments, questions?

Abstract

Despite Modernism’s influential place in our architectural heritage, many significant Modernist and other recent buildings are endangered because of neglect, perceived obsolesces, or inappropriate renovation, and some are even in imminent danger of demolition. In response to these threats in 2006, the World Monuments Fund launched its Modernism at Risk initiative.

This presentation will illustrate that modern buildings can remain sustainable structures with vital futures. Along with the WMF/Knoll Modernism Prize, which is awarded biennially to recognize innovative architectural and design solutions that preserve or enhance modern landmarks, the presentation will highlight the special challenges and promising opportunities of conserving modern architecture.

In many preservation battles, one can make the case that a building is worth saving because it is beautiful and historic. Those two factors have less currency in the fight for modern buildings because many citizens simply do not like modern building, and often deem them visually unappealing.

Further, by definition, many modern buildings are too recent to be “historic” in the traditional sense and many have not legal protection because they are too “young” to qualify for landmark status or other designations. Far too long, many municipalities have routinely demolished postwar modern buildings. Deemed unsightly, or outdated, they have been bulldozed only to be re-placed by new structures that essentially serve the same purpose — without giving the original buildings a second chance, or a second thought.

Speaker Biography

David E. Bright, Senior Vice President, Communications, Knoll, Inc., is responsible for print and online communications, media and public relations and is the lead manager for the architect and design managers team. He also serves as the Knoll liaison with the Clinton Global Initiative and the World Monuments Fund.

Prior to rejoining Knoll in 2003, David spent seven years working for a range of industrial and design-focused businesses. He serves as Treasurer of The Summer Camp, Inc., a non-profit organization, and is a member of the advisory board of Manitoga/The Russell Wright Design Center. David earned an A.B. from Brown University and an M.B.A. from New York University Graduate School of Business Administration.

This presentation is part of the Mid-Century Modern Structures: Materials and Preservation Symposium, April 14-16, 2015, St. Louis, Missouri. Visit the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training to learn more about topics in preservation technology.