Last updated: September 2, 2021

Article

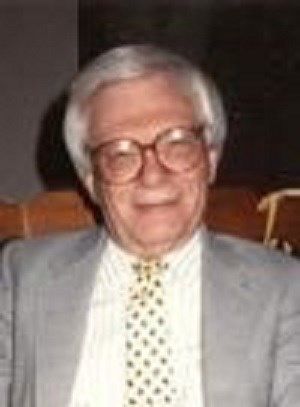

Milton F. Perry Oral History Interview

NPS

ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW WITH MILTON F. PERRY

JULY 18, 1991LIBERTY, MISSOURI

INTERVIEWED BY JIM WILLIAMS

ORAL HISTORY #1991-8

This transcript corresponds to audiotapes DAV-AR #4334-4337

HARRY S TRUMAN NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR

EDITORIAL NOTICE

This is a transcript of a tape-recorded interview conducted for Harry S Truman National Historic Site. After a draft of this transcript was made, the park provided a copy to the interviewee and requested that he or she return the transcript with any corrections or modifications that he or she wished to be included in the final transcript. The interviewer, or in some cases another qualified staff member, also reviewed the draft and compared it to the tape recordings. The corrections and other changes suggested by the interviewee and interviewer have been incorporated into this final transcript. The transcript follows as closely as possible the recorded interview, including the usual starts, stops, and other rough spots in typical conversation. The reader should remember that this is essentially a transcript of the spoken, rather than the written, word. Stylistic matters, such as punctuation and capitalization, follow the Chicago Manual of Style, 14th edition. The transcript includes bracketed notices at the end of one tape and the beginning of the next so that, if desired, the reader can find a section of tape more easily by using this transcript.Jim Williams reviewed the draft of this transcript. His corrections were incorporated into this final transcript by Perky Beisel in summer 2000. A grant from Eastern National Park and Monument Association funded the transcription and final editing of this interview.

RESTRICTION

Researchers may read, quote from, cite, and photocopy this transcript without permission for purposes of research only. Publication is prohibited, however, without permission from the Superintendent, Harry S Truman National Historic Site.ABSTRACT

Milton Perry [1926 to August 20, 1991] served as the first curator of the Truman Library until his retirement in 1976. Perry had the unique benefit of working with his historical source and, as a result, worked closely with Harry S Truman to develop the exhibits in the library. As Perry relates his many stories about working with Truman, he allows the reader to understand Truman’s dedication to the library and the public who came to visit and better understand the office of the presidency.Persons mentioned: Herman Kahn, Wayne C. Grover, Harry S Truman, Margaret Truman Daniel, Vietta Garr, Ralph Truman, J. Vivian Truman, Edgar Hinde, Sr., Millard Fillmore, Zachary Taylor, Philip C. Brooks, Rose Conway, Stuart Symington, Ginger Rogers, Bill Randall, Hubert H. Humphrey, Desi Arnaz, George McClellan, Abraham Lincoln, Douglas MacArthur, Winston Churchill, John F. Kennedy, Bess W. Truman, Thomas Dewey, Lyndon B. Johnson, Joe Kennedy, Stu Jackson, Richard M. Nixon, Dwight D. Eisenhower, Lloyd Stark, Spencer Salisbury, Joseph McCarthy, George Catlett Marshall, Napoleon Bonaparte, Edgar Arthur, Jonathan M. “Skinny” Wainwright IV, George S. Patton, Jr., George Armstrong Custer, Libby Custer, Sam Rayburn, Ben Lear, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Steve Early, Eleanor Roosevelt, Joyce C. Hall, Jim Pendergast, Dexter Perry, Howard Adams, Nile Miller, Lloyd Stark, Erle Stanley Gardner, Barbara Perry, Madge Gates Wallace, Lorne Greene, Dan Blocker, Jack Benny, Thomas Hart Benton, Mike Westwood, Bill Storey, Greta Kempton, George Wallace, and Rufus Burrus.

ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW WITH MILTON F. PERRY

HSTR INTERVIEW #1991-8JIM WILLIAMS: This is an oral history interview with Milton Perry. We’re at the Jesse James Bank Museum in Liberty, Missouri, on July 18, 1991. The interviewer is Jim Williams from the National Park Service, and Connie Odum-Soper is running the recording equipment.

Well, first of all, I’d like to find out a little bit more about you before you became associated with the Truman Library. So, could you tell me where you were born and—

MILTON F. PERRY: Yeah, I was born in North Carolina, and I grew up though in Norfolk, Virginia, and after World War II, I went to college on the GI Bill. And I had several choices, so what I was doing while I was making my choice, at that time William and Mary had a branch of their school in Norfolk set up strictly for veterans. It was called the Saint Helena Extension of the College of William and Mary, and it was in a former Coast Guard base, as a matter of fact. And so I enrolled there and I did some of my earlier schooling there, and then at the other branch, which was the permanent branch, was called the Norfolk Division of the College of William and Mary—today it’s Old Dominion University—and I did go between those two.

And after my freshman year, we all went up to the main campus of William and Mary, and that was when I had to make the decision did I want to stay with William and Mary or did I want to go somewhere else. Because my first major thought had been

journalism. I wanted to get into print journalism. But I did a lot of investigation and decided that I really didn’t want to do that after all, but I didn’t know what I wanted to do. So I took a battery of psychological tests at Williamsburg that the VA was giving all the GIs, and it turned out that they felt I could be a good teacher in English or history or literature, and so I started majoring in those subjects.

And since it was at Williamsburg, I was able to become associated with some of the historical activities that were going on there, and then in graduate school I got full-time jobs in the craft shops division, in which I was assistant manager of all the craft shop operations, which included things like, oh, the wig maker and the candle maker and the carpenter shop and the printing shop and things like that. And then after I got out of school, I became director of the archaeological laboratory and was at the archaeological program for about a year or so. I enjoyed that so much that an opportunity came up in the state of North Carolina to restore a nice Civil War fort down at Beaufort. Fort Macon it was called. I took it and liked that, and decided I would stay that as my career. So then I applied for it and got a job as curator of history of the West Point Museum up at the U.S. Military Academy. And I loved West Point, and I would be there yet if it hadn’t been for Harry Truman.

WILLIAMS: So when did you go to West Point?

PERRY: In 1953.

WILLIAMS: And when did the call from Independence come?

2

PERRY: Let’s see, that would have been in late 1958, I think it was. The first I knew about it was the day before Armistice Day, I think it was, the director of the Franklin Roosevelt Library, Herman Kahn, called me and asked me if I would come over to the library on Armistice Day because the Archivist of the United States was flying out from Washington and wanted to talk to me. And I . . . “Sure,” I said, “that would be fine.” I’d been over there before, and I’d known some of the people on the staff. But then I asked him, “What is it that he has in mind?” And he said, “Oh, I thought you knew. We’re recruiting for a curator for the new Harry S. Truman Library that’s being developed in Independence,” which I hadn’t known a thing about.

So I went up there, and Dr. Wayne C. Grover was the Archivist of the United States in those days, and we spent all day. We visited the place, and I talked to all the people that were there. Of course, I had known some of them. Dr. Whitehead was the curator at that time, and I knew him. And then after it was over, he said, “Well, we’d love to have you go to Independence and take this over because I think you could do it, and I’d like to get younger people in these new institutions.” And so I couldn’t answer at that time, and I went home, and I had to discuss it with my wife, because I had three children and one of them was in school, and I loved West Point, and we liked living up there and so forth. So I hemmed and I hawed and I hemmed and I hawed, and I checked with the personnel office in West Point to find out what the probabilities of advancement would be, and comparing what they would offer me in Independence with what I had there and trying to project it for five years, and all these things, and I really wasn’t sure.

3

Then one day the phone rang, and it was Mr. Truman himself, and he simply said that “I don’t want to be accused of trying to push you in any direction you don’t want to go, but I’ve heard that you’re being considered and I’ve heard good things about you, and I just want to say I know about the museum in West Point and I like it very much, but I just want to say that if you do accept it that I promise you that you’ll be able to run it in a thoroughly professional way, and I’ll be here to give you any assistance you want if you ask it.” So that kind of tilted the whole thing in that direction, so I accepted the job.

WILLIAMS: And when did you move out?

PERRY: It was in January of 1959, I think it was.

WILLIAMS: Did Mr. Truman keep his promise?

PERRY: Oh, my, yes. He was delightful. You know, I think I have been in a position that museum curators would love but not many of them have: my original source was just sitting there in an office right down the hall, and I had complete entree and carte blanche to go in and talk to him at any time about any of the subjects. And it was nice to find things like the sign on his desk, “The Buck Stops Here,” and to go down and say, “Mr. President, what’s the background of this?” And I did that many, many times.

And sometimes he could remember, and sometimes he couldn’t. For example, all he remembered about that sign was the person who gave it to him. And so then we had to kind of research it out and find the background after that. But his clues were very good. And a lot of times he’d remember. He was very proud of things. The shah of Iran and the king of Saudi Arabia gave him some beautiful gold-encrusted swords with diamonds and things in it, and he used to love to tell jokes. He said they

4

were at a reception one time and . . . let’s see, one of the senators was from Oklahoma, who built all the lakes in Oklahoma—I forgot his name now—was coming through the line, and Mr. Truman said he told Margaret if he’d trip him and make him slide across the parquet floor he would give her one of those swords with all those diamonds in it. But she refused to do it. He was always full of little stories like that, which made it so much fun.

WILLIAMS: How much input did he have in the design and operation of the museum?

PERRY: He did not come through and say, “You ought to do this.” He didn’t preconceive. He said, “I am here to help, and I will give advice when asked and suggestions,” but he never came through and said, “Design this museum this way or that way.”

The only time he came close to that was when the 35th Division Historical Association, with which he had served in World War I, and Ralph Truman, General Ralph Truman, who was his first cousin and had been commanding general of that beginning in World War II, and they were very close. They were really like brothers. They were much closer than he and Vivian was, for example. He was very fond of Ralph, and Ralph of him. Anyway, they prevailed upon him to allow them to raise money and finish off an unfinished section of the library in the basement of the museum and dedicate that as the 35th Division Room. That is as close as he ever came though to doing that, because he lent himself fully to that. And then he lent himself so that we were able to collect a fine collection of World War I militaria that’s there today, as well as lots of archival material, lots of diaries and letters and things that these men had had in World War I, especially Battery D material. So we were able to benefit a great deal from

5

that, and we even managed to get one of the few remaining 75-millimeter cannon of World War I from the Army for that.

And that was a funny story, because he called me one afternoon and said, “They just called me and said a 75-millimeter cannon is down in the west bottoms of Kansas City at a freight warehouse,” and he said, “Would you like to go down and look at it?” So I said, “Yes!” So we ran and I got the car and we drove down there, and it was in one of these big trucks, semis, and we were looking at it. And the man who was shipping it was very proud of himself bringing it here, but somebody had managed to unlock the mechanism and the gun was sort of . . . the carriage was slid back. And he says, “But you know, we don’t know how to get this thing moved back, and we have to do it before we move it out.” And they fiddled, and they messed around with it, and they messed around with it. Finally, Mr. Truman said, “Let me look at that for a minute.” He walked over and studied it and reached over and just touched one thing and it went, sst! and slid right back up where it was. And he grinned and he said, “See, I haven’t forgotten my old artillery manual after all, have I?”

But then when we brought it over to the library, the problem was how do you get it in the basement? So we had hired a . . . They had a local National Guard unit that came there, and they had all these young men there, and they didn’t know how to take that thing apart because they had never seen that cannon. That was an antique, as far as they were concerned. And so Edgar Hinde was there, and Edgar used to be postmaster in Independence, and he was . . . I think he was commander of the . . . I believe the 128th Artillery. Anyway, he was an old friend of Truman’s. In fact, he had appointed him postmaster. And so he was there, 6

and they were trying to figure out how to get that artillery piece apart so we could get it to the basement. So finally Ed said, “Well, I think I’ve got an old manual at home. I’ll run and get it.” So we all sat around and drank coffee while Ed went home and got the manual and came back, and it was all in French. [laughter] And so here we were where we began. But luckily one of the young men in the artillery battery was pretty fluent in French, so he was able to translate it for us and then we were able to follow directions, and we took it apart piece by piece and lowered it down and assembled it. [chuckling] But when Ed came back with that French manual, everybody just looked at him and shook their heads. [chuckling]

WILLIAMS: How much of a museum was there when you arrived?

PERRY: It was just part of the first floor, what we call . . . When you go in, there’s the lobby, and then to the left there is a strange room that you can only use for so much because it’s sort of a lobby for an auditorium. They made a mistake when they designed the building. The auditorium does not have its own entrance. And one thing, they should have put its own entrance to the auditorium. So everybody had to go through the lobby, and then you have to go through this large room to get to the auditorium. Well, you can’t put any exhibits in there because it’s a pass-through area. But to the right, you go through a little area, and there’s a balcony and you look over, and then we hung a huge Persian rug up there.

Then beyond that was the main gallery, and it was called the Presidential Room, and it was his favorite exhibit. It was an exhibit that the . . . on one side was an exhibit that the National Archives had put together before and had used, and in it was a document written or signed by every President of the United States. And there were some interesting things. 7

There was a copy of the Emancipation Proclamation there, there were Cleveland’s Civil Service Proclamation, and a lot of things like that were in there, some very important ones and some very insignificant. Like Millard Fillmore apparently would sign anything of significance, you see. And Zachary Taylor was president for thirty days, so he didn’t have a chance to sign very much. But anyway, there was something written and signed by every one.

And then on the other side was his favorite theme, and that is the six jobs of the president. He loved to talk about that. That was one of the things he loved very much, and he loved to talk to people about the six duties of the president: he was commander in chief, and chief of state, and head of the foreign policy, and so on. And each of those exhibits used that as a theme, but there were things selected for the Truman collection to illustrate that theme. And I think that was a very, very important exhibit, and I’m very sorry that the library now has taken it out and they don’t use it anymore, because he was very fond of that.

And the other thing that he was very adamant about—and I’m afraid if he were here today he’d be very unhappy—he proclaimed over and over again, “This is not to be a memorial to me. It is to be a museum about the office of the presidency. And if you want to talk about how I conducted the office of the presidency, fine, but I do not want this to be a memorial to me.” He even wrote things about “no memorial to me.” He was very strong about that. And I’m afraid if he went over there now he would not be very happy, because it is a memorial to him. I think they could hit a level ground in that, because I think they could do . . . People are interested in the background of who Harry Truman was, the person, but 8

I still think it would be important to preserve how he conducted the presidency and the "six jobs" theme that he liked so much, because people could relate to that very quickly. And today they go through, and it’s just the story of one man. But his great dream of trying to interpret the presidency for the public, especially the youngsters, is not being carried out like I think he wished it would have been.

WILLIAMS: When was your first face-to-face meeting with Mr. Truman?

PERRY: Right after I got there. Our director then was Dr. Philip C. Brooks, and I hadn’t been there more than an hour and he says, “Well, come on in and let’s meet the president.” So we went in, and I remember him sitting there behind his desk, and I thought, “Gosh, he looks just like he does on the newsreels on television.” He had that same grin and that same personality and all. And he got up and we shook hands, and he sat down and he said, “Boy, am I glad you’re here. We’ve got a lot of work for you.” He said, “This museum has just begun, and,” he said, “to me, this is one of the most important things we can do is to reach the public.” He said, “I know that through the archives we reach people, but we reach the man on the street through the museum,” and he said, “That will be your job. And I’m here to say what I told you before. I’m here to help you any way I can. All you have to do is call upon me, and if I can’t find it out, I’ll see if I can’t find it out for you.”

And then he got to reminiscing about how he was so excited about this new dimension of what former presidents can do. And I remember one word he used, “All the other fellows . . .” meaning the former presidents. That struck me because I never heard of anybody putting the other presidents together as “fellows.” He said, “None of the other fellows had

9

an opportunity to do this.” He said, “I got the idea from Franklin Roosevelt, but he died before he could come and do it like this. But when I was up there at his funeral and I saw that library, I knew that’s what I wanted to do with my things.” And I thought to myself, It’s interesting calling them the “other fellows,” but after all, he’s one of them and it’s kind of like a club, and you talk like a group of people that you are a part of.

So he lived up to his promise, as I said before, but I do vividly remember that first time. In fact, he autographed a photograph and gave it to me, which I was very proud of, and I took it home and showed it to my family. I was very excited.

WILLIAMS: What was Dr. Brooks like as a director?

PERRY: Dr. Brooks was a very nice person. [chuckling] He used to complain because one of the earlier newspaper articles about the library described him and said he had a “filing cabinet mind,” and that just . . . that insulted Phil. [chuckling] I mean, he complained about that for years, “a bureaucrat with a filing cabinet mind,” because he said, “I guess that’s what they think of all of us archivists.” And he appreciated the museum, but he didn’t understand the museum’s function. And that’s the problem with archivists. They like the written word, they like the paper, the document, but they don’t understand that that is a very minor segment of the people who access to that stuff, and that [to] the bulk of the people, the museum is the library, not the archives. And I used to think it was a mistake to put these institutions under the National Archives. I used to think maybe the National Park Service would be better equipped to do it because they are more public-oriented, and the archives wasn’t. They have

10

become more so since then, but I think it’s because they’ve been forced to do it.

But, for example, I was going in one day and some of the archivists were going through and they were going through a lot of public opinion mail, which are these millions of letters that the people have written to the president, and they were detaching the envelopes and throwing them in trash baskets away. I picked up some of them, and they’re hilarious. I mean, people just made a big joke out of the way they addressed the president. And I said, “My God, what are you doing?” They said, “We’re throwing this away to reduce the volume on the shelves.” I said, “Well, save those wastepaper baskets and put them in my office and let me go through them.” And so I saved thousands of these things, and one of the most popular exhibits I ever did was “How do you address the president?” It just had several hundred of these things—I’m sorry, scores of these things up—and some of them said, you know, one of them was, “To President Truman, wherever he is now.” And others I remember was . . . one of them just drew his picture on the envelope. And another one just said, “HST.” That’s all it was, you know. And I thought that was great fun, you see. But, you see, archivists, they don’t understand that. They do not understand that the public loves these things. And this is why, I think, in these institutions they need directors who are very cognizant with the museum function and that. And Brooks tried but he never fully understood that area. And he was always very, very conservative. He was a little reluctant to make new things.

Mr. Truman made one of the things I thought was the most interesting. One day he called me in his office and he said, “You know, 11

Perry, I see these yellow school buses just come up here by the score. What do you do with those kids?” I said, “Well, we put them in the auditorium, we talk to them, and then we have these docents that I’ve trained and they take them on tours.” And he said, “Well, do they ever ask to see me?” I said, “Well, sure they do, and some of them do, as you know, and they come back here.” He said, “Well, I was just thinking.” He said, “When I was in Washington and I had these press conferences, reporters would come in. I learned quickly that the best way to get through to them on what they want is to let them ask me questions and not for me to read all these statements and things to them.” He said, “Do you think that if we put those kids in the auditorium, I would go out there and let them ask me questions, do you think they’d like that?” And I said, “Mr. President, they’d love it, and they’d remember it for the rest of their lives.”

So, anyway, we worked it out. He said, “You put them in the auditorium, you come and get me and I’ll go back.” I said, “Well, suppose you’re busy?” He said, “I’ll quit and come.” “Suppose you’re on the phone?” “I’ll tell them to call me back.” “Suppose you’re talking with somebody?” “I’ll bring them with me.” I said, “Well, just interrupt you?” And he said, “Yes.”

So what I would do, as you’ve seen that office, just to the left of the desk there’s a little anteroom where Miss Conway the secretary’s office was. And I’d just go and stand there at the door and I’d catch his eye, and he’d say, “Perry, you got a group of youngsters for me?” “Yes, sir.” I remember one day Senator Symington was there. He said, “Stu, come on, I’ve got something more important to do than sit here and talk to you. Come along,” and he dragged him out. And Ginger Rogers and Bill

12

Randall and Hubert Humphrey, anybody who happened to be there he dragged them with him. That was a bonus, of course.

Well, the kids, naturally, were thrilled to death, and some of them were so thrilled they couldn’t talk. My favorite answer to all those hundreds of questions was a little boy who stood up and said that whenever he has to stand up and give book reports and things in front of the class he gets so scared he can’t talk, and that he said he wondered if that ever happened to the president. The other kids started laughing at him, and Mr. Truman quieted them down and thought a minute, and he said, “Now, young man,” he said, “let me tell you something.” He said, “I don’t care where you will go in life and how important you’ll get—you may be President of the United States—but whatever you do, whenever you have to get up and talk to a group of people, if you’re not concerned with what you have to say and how it will be received, it’s going to mean you don’t have anything worth saying.” And I thought, “What a wonderful thing to inspire a kid.” That was a beautiful . . . a beautiful thing.

Then, as we were walking back to his office, and Ed Hinde was with us, and he said, “You know, I started to tell him about my first political speech.” I think he said it was in Sugar Creek. He said, “I was so scared after I gave it I threw up.” And Ed says, “Yeah, Harry, that was the worst damn speech I ever heard in my life by anybody.” [laughter]

But I prevailed upon him to let us tape-record those sessions, and so there’s hours and hours of really good question-and-answer sessions with some good history in there. Because what he would do with those kids, if you or I were to ask questions, he would give a really quick answer and say, “Well, it’s in the files,” or something or other. But with the children, 13

he would be very careful. He would give the background and then he would build to it, and sometimes ten or fifteen minutes. There was a lot of history in those question-and-answer series that you and I wouldn’t get that somebody is probably going to tap one day and find some interesting material from it. But he loved the kids, and he loved to stroll through the museum, and especially to see the kids.

I remember sometimes we’d just walk through, and I remember we’d be standing looking at a case, and people would come in, and they’d casually look at him. And then suddenly they’d take a double-take, and then first thing you know, they’re running to him and wanting him to sign his autograph. He didn’t mind. He liked to have his picture taken. Didn’t mind. He said, “The time to worry about that is when it’s not happening.” And he really put down some people. I remember one time Desi Arnaz came to the library, and he was waiting for Mr. Truman. And they went out together into the front, and people came in and started asking Arnaz for his autograph. He says, “I never sign autographs.” And Mr. Truman looked at him and he said, “Young lady, come here.” He took it over, and he signed it and gave it to her, and he said, “You know, the time you ought to start worrying about it is when they stop asking to sign your autograph,” and kind of walked off, you know. I thought, “Boy, what a put-down that is.” But he liked the people, and he loved people. He loved visiting with the people, because he was a man of the people.

WILLIAMS: He was in his office nearly every day.

PERRY: Oh, yeah. And you see, I got to know him better than any of the other staff members did, even better than Dr. Brooks, because we discovered that he also came in on Saturdays when he was the only one in the office. So they

14

put me on a Tuesday-through-Saturday shift so that I would be there with him and people would come into the auditorium or go back and see him. And most of the times it was just he and myself and the people at the front and the guards. And he said, “I come in Saturdays because I can get all this work done without interruptions.” No phone calls, no visitors.

But one of the things he did, he’d call me in a lot and he’d say, “Now let’s go through the mail,” because he loved to go through the mail and get what he called “the crank letters” and read them. Then he’d just laugh. And these people would write and say, “You’re a no-good SOB”—you know, they’d blast him off—and he’d laugh, and he’d say, “I can’t do this in the week because Rose and all those people throw them away before I can get them. So I come in here and I read them on Saturday before they get to them.” [chuckling] And I said, “Don’t they scare you?” He said, “No, these people are just blowing off steam.” And he said, “You know, they’ll write and they’ll forget it and go on to something else.”

And he loved it, but it also gave us a chance to visit. Because a lot of times he would call me up and say, “The coffee’s ready,” and I’d go down there, and he would have a couple of cups of coffee. Or sometimes he’d come down the hall with two cups, and he’d come in my office, and we’d sit and we’d chat. And we talked about all kinds of things.

We both were Civil War buffs, and he was a very good Civil War scholar and historian, and he walked those battlefields in the East. I think he’d been in all of them because he could tell you facts and details and positions. And Chickamauga and Bull Run and Yorktown—and you just name the battlefield—Antietam, Gettysburg—he knew them, and he knew the positions of them. Because he had a retentive mind. I don’t think that 15

man ever forgot anything he ever read. I swear, I don’t know how he did it. But I did a little Civil War book called Infernal Machines, about the secret weapons the Confederacy had used, mines and torpedoes and land mines and things like that. I gave him a copy, and he really enjoyed that. He talked to me about it. And then since I’d grown up in Norfolk and the Chesapeake Bay and all, we talked a lot about the war there, and the Monitor and the Merrimac, and McClellan and Lincoln’s problems with his generals. He said, “I’d have fired that son-of-a-bitch.” He said, “Lincoln had too much patience.” He said, “I’d have done the same thing with him I did with MacArthur.” He said, “He was a prima donna,” and he said, “Lincoln’s big mistake was that he didn’t handle him like I did Douglas MacArthur.” He said, “Because MacArthur was trying to be a proconsul in Tokyo,” and I said, “We’re not the Roman Empire, and we don’t have proconsuls.” And you have to obey the orders of the commander in chief.” He said, “That’s all there is to it.” So he had a lot of good observations on things like that, which I thought was very interesting.

And then he loved local history, too. We tramped the battleground at Westport and Byrum’s Ford. In those days, Byrum’s Ford didn’t have the Pepsi-Cola plant and stuff up there, you know. And Bloody Hill, he knew about that, and Byrum’s Ford Crossing. And he always claimed there were cannon buried under there, because there were some cannon lost during that fording and they got swept away and buried in the mud of the Little Blue River there. But I’ve never found anybody who had a spectrometer to look down there and see if they’re in there. But that’s a legend that he repeated, and I’ve heard other people mention it, too.

16

And then he used to talk about the Civil War, raiding the Young farm. I remember one time he talked about his grandmother, and the Yankee cavalry came up and took all their food out of the smokehouse, and so she said, “Well, what are we supposed to eat?” And he says, “That bastard must have been from Boston, because he repeated, ‘Well, lady, as far as I’m concerned, you can eat grass’”—[ pronounces it grawss] the word “grawss” just handed right on down the family.

Then he remembered about his dad used to take the corn to Watts Mill to be ground, and he talked about how the bags would be piled way up high on this wagon, and he’d be sitting on the top, and he would sway back and forth. He’d have to hold on to keep from being thrown off. Full of little stories like that that he loved to relate.

But he was a great reader and a practical joker. He used to tease me, and he learned that I hate static electricity, and his office has carpet, thick shag, and you know you touch something and you snap. So he’d notice that. So he would bring in . . . Like I remember one time when new books would come in, he’d put them on the shelf, and he’d call me over and say, “Now, Perry, I want you to see this book.” I remember especially one time Winston Churchill had sent him a book. He said, “Look what Winston has sent me.” And I’d go over and look at it, and he would shuffle his feet, and then he would touch me right here and it would snap, and then I’d do that and he would just laugh. You know, he just loved to do it.

Then finally one day he got real serious. He said, “I hope that you don’t get angry about me teasing.” And I said, “No, sir, why should I?” He said, “Well, I just want you to know I only tease people I really like.” And I said, “Well, that’s fine with me.” Because I’m a big teaser, too. I

17

think that’s a country trait, you know. I love to tease, too. But yeah, he would touch me like that.

And then we used to have this controversy about when he’d go out to talk to the kids. We couldn’t figure out who would open the door for whom. And when he would open it for me, and I said, “Mr. President, this is not right.” Got to change tapes?

[End #4334; Begin #4335]

WILLIAMS: You were telling a story about . . .

PERRY: Well, where did we break off? I’ve forgotten. What were we talking about, Connie? [pause –- no response] Who was paying attention? [chuckling] I don’t remember what we were talking about right now.

WILLIAMS: Oh, opening the door into the auditorium.

PERRY: Oh, that’s what it was, yeah. Yeah, that’s right. Because when we started, you know, if he got there, he would open the door, and then, you know, so I would kind of rush to get in there. I said, “Mr. President, this is not right.” He said, ‘”What do you mean?” I said, “I should be opening the door for you.” He said, “Why?” I said, “Well, because of who you are.” He said, “Look, whoever gets to the door first opens it.” I said, “But you’re the former president.” “That don’t make any difference.” I said, “Well, you’re a lot older than I am.” He said, “No, that won’t make any difference at all. Don’t try that on me.” So we never did settle that. Whoever got to the door first opened the door for the other one to come in. And I was kind of embarrassed because sometimes we got on the stage in the auditorium and he would open the door and shove me out first, you know? [chuckling] We never resolved that.

18

But he was a delight to work for. And you know, I never . . . I only saw that man get upset one time. The “Give ‘em hell, Harry” was all an act. He was not that way personally. But one time we were out, going to talk to the youngsters, and we had to cut through his office, through the research room, and you go out that way. And there was a lady who had been an Air Force officer who was a new librarian, and she was very abrupt. She was not a personable person. Anyway, there had been a little caged-off area between the research room and his office where Miss Conway would put things given to him in there, and it was just kind of a wire cage just at one end of the room. And so this lady thought that they could add that to the research room. But instead of going through Dr. Brooks and all that, she walked over and snapped off to Miss Conway, in not a very nice way. And Miss Conway was fiercely defensive of the president, so she told the president. Anyway, as we went through, some way we had walked through, and then I turned around, and he had veered off and he was up at that desk. He said, “You’re the one who wants to take all my space away from me. Well, you’re just not going to have it, that’s all there is to it. I’m not going to give it to you. I don’t like the way you approached it, and you’re not going to have it.” And he just walked off and left her. He mumbled, “She’s trying to take all my space from me. She’s trying to take my space from me. I’m not going to let her have it.” You know, he was really upset about that. Later on, she went through Dr. Brooks, and he was glad to make the space available, but he just didn’t like her attitude. But that was the only time I ever saw him really angry or upset.

19

In fact, he would go out for the press conferences, and we would be walking along, talking and laughing and joking, and he gets out there and he was at that podium, it’s “Give ‘em hell, Harry.” He’s banging on the podium, he’s pointing to them and all that. And one day I said, “Mr. President, you know, you politicians are just good actors, aren’t you?” He said, “Well, that’s true.” I said, “You ought to get the Academy Award for the performance you put on out there.” He said, “To be a good politician you have to do that.” And I think he’s probably right. I think, you know, they do overemphasize themselves to make a public image. But “Give ‘em hell, Harry” was not Harry Truman the person. It was Harry Truman on a stand someplace. And he appeared to be very angry, but he wasn’t. Because I’d seen him when he was “just giving those reporters hell,” as he said, coming back, smiling and laughing and joking.

One of the things I remember was one morning he called me at home, one Saturday morning in 1960. I think it was in . . . it had to be July. He says, “Can you come on over earlier?” Because Phil Brooks was gone. He said, “Can you come over earlier?” He said, “I’ve got Gene”—Gene was his male secretary—“I want to have a press conference in the auditorium in a little while.” And I said, “But do you have time? You’re supposed to go out to Los Angeles for the convention.” He said, “Well, I’m going to talk about the convention.” And I thought, “Uh-oh.”

So we set it all up and we come out, and that’s when he got up and he stunned everybody by lecturing Jack Kennedy. He said, “Senator, are you mature enough to be president? Are you sure you want to be president? Are you sure the country is ready for you?” Etcetera. And then he said, “I don’t think so.” And he says, “My man is Stuart Symington. 20

But since this convention is fixed anyway, I’m not even going to bother to go.” And that’s when he dropped the bombshell: “I’m not going to the convention.” And he had his bags. The bags were right there. In fact, Gene said, “I was as stunned as anybody else. He hadn’t even told me that.” I don’t know whether he told Bess that even or not, truthfully. And everybody was just stunned that he boycotted the convention, and he didn’t go.

And then about two weeks later they had what I call “a love feast.” Jack Kennedy came in with Stu Jackson and Hubert Humphrey and Lyndon Johnson and the whole passel of them. And they all came in, and they were all at a long table in the auditorium, and they had this . . . they all make up. And so somebody asked Mr. Truman in front of Jack Kennedy, and he said, “Well, didn’t you say the convention was fixed?” He said, “Yeah.” He said, “Well, was it?” He said, “Yep.” He said, “Why are you here?” He said, “Because the senator is a nominee of my party and I’m a loyal Democrat.” [chuckling] And then he campaigned for Jack Kennedy, as you well know. He went down to Texas and told those Baptists down there if they didn’t elect him, they deserved what they got. And he believed that.

But he detested old man Joe Kennedy. Oh, he hated that man! He told me, he said, “I never want to have anything to do with that son-of-a-bitch anymore. I never want to see him. I don’t want to talk to him or anything.” He said, “His son’s a different matter but,” he said, “that man, he would tell me he would back me and turn right around and go behind my back.” And he said, “I have nothing to do with him.” And he said one time there was something about when the train was . . . when the whistle-

21

stop train was going to Boston, he wouldn’t let him on his train. I guess Joe Kennedy had a lot of enemies. I’m sure Harry Truman wasn’t the only one. But he could not stand that man.

And Richard Nixon he detested most of all. He was one of the three people on his hate list. Let’s see, it was Richard Nixon. There was, I think . . . was it Stark? Governor Stark of Missouri? And I forgot who the third was? Do you remember the third one?

WILLIAMS: Ike?

PERRY: No, no, not Ike. No, they made up. It was somebody from here. Gosh, I can’t remember.

ODUM-SOPER: Salisbury.

PERRY: Spencer Salisbury, that’s who it was. Spence. I knew Spence. Spencer Salisbury. In fact, Spence Salisbury, you know, had a bar downtown and he had Harry Truman’s picture painted in the urinal. That’s what he thought of Harry Truman. [chuckling] Did you ever hear that, Connie?

ODUM-SOPER: No.

PERRY: Yeah. Yeah, that’s what he thought of Harry Truman. And see, they had been great friends in World War I. They were both in the artillery. Spence was a good-looking guy in those days, tall, dark-haired, a little mustache, dashing. He looked more like an English artillery officer, I would say. But anyway, they were in this bank together over in Englewood, and this bank got in a lot of trouble, and Spencer had to go serve time on account of it, and Harry Truman got out of it. And Spencer claimed that Harry Truman was as guilty as he was and that he kind of dumped some stuff over to his side, so he became a very bitter enemy of Truman’s.

22

And Stark had been a governor of Missouri, and they’d got into it because Truman claimed that Stark had said he was going to support him one time and he turned around and supported an opponent, and he thought that was . . .

“And Dick Nixon called me a traitor in Houston. Nobody ever calls me a traitor.” Well, that was strong because, you know, every politician thinks they’re the most loyal American around and, you know, you don’t call them a traitor. And Nixon always said, “I called him a traitor to the democratic principles,” or something like that.

And then he didn’t have him on his list, but he thought Joe McCarthy was just as bad as the rest of them. In fact, you know, when they were getting ready to dedicate the library and they had the cornerstone, the newspaper headline had a story about Joe McCarthy dying that day. Truman had put that newspaper in the cornerstone, and somebody took it out and told him that wasn’t the thing he should put in the cornerstone of the library [chuckling] because he was so pleased that McCarthy had died.

But, see, that was the heart of the fracas between Ike and Truman. It was when Ike was doing his campaign in Wisconsin and McCarthy got on the train. And then while he was on that train he made the speech denouncing George Marshall, called him a traitor, a Communist sympathizer, and Eisenhower didn’t take up for Marshall. Truman thought that was rank ingratitude. As he said, “George Marshall made Ike what he was today.” He said, “He jumped him over a whole bunch of generals, he personally selected him, and he owed that loyalty to him.”

23

And yet that was strange because, you see, Truman and Eisenhower go back a long ways. He and Edgar [Arthur] shared a room and worked in the Commerce Bank when they were young men. In fact, Truman said, “He was so dumb when he came in off the farm that he’d never seen an electric light, and so when he got up to turn on the electric light, he struck a match to light the electric light.” I swear that’s what he said, at that boardinghouse they lived on Troost Avenue. And he knew Ike back in the ‘30s when he was a reserve officer and Ike was . . . and they would go to . . . Let’s see, what’s that military base in Junction City? Which one is it?

ODUM-SOPER: Fort Riley.

PERRY: Fort Riley. They’d go there for summer training. Wainwright was there, “Skinny” Wainwright, George Patton was there, Eisenhower was there, and they’d all play poker, and they’d all drink. He said Wainwright could drink everybody under the table, Patton could out-cuss everybody, Eisenhower could out-think everybody. And he wanted—in fact, tried to encourage—Ike to run for president after him. But the Republicans, he went Republican. And he used to show, when Eisenhower was president, Eisenhower had made a statement saying that when he turned down the Democrat request that no general should ever run as president. He used to hold that up and say, “This is the best reason in the world why he shouldn’t be president. He said it himself.”

And I had known Eisenhower before I came to the library. When I was at West Point, Eisenhower was president. And he had played football for the Army, and so he used to sneak on a helicopter and fly up and watch the brave old Army team practice on Thursday nights. And when he did, he would usually bring two or three people with him. and he’d tag them 24

over to the museum. Because at the end of World War II the government of France had presented him one of Napoleon’s swords in gratitude, and he had put it in that museum. And he would drag these people over to see the sword, and so I would be detailed as curator of history to receive him. So I got to know him several times.

One time he happened to come in when we were just getting ready to open a display, because I had found wrapped up in a paper parcel in the bottom of an old file cabinet in the old post library a map which was the map that George Custer had with him the day he was killed, and which had been gotten back a couple years later by one of the officers. And Libby had said it was the only thing her husband had with him that day she ever got back. So we were doing an exhibit and opening it at the time Eisenhower came in. He was fascinated, and we both made the front page of the New York Times together, which of course thrilled me. I mean, I never thought I’d get on the front page of the New York Times for anything, and there I am with Eisenhower. [chuckling] But he really enjoyed it, and he loved the museum and he liked history.

Well, anyhow, after he left being president, he hadn’t been out very long, and we got a call from the People to People organization in Kansas City saying former President Eisenhower was coming to help dedicate it. Mr. Truman was on the board of it, and they wanted to know if Mr. Truman would come down and see him. Mr. Eisenhower would like to see him. Well, I was in the office when Ralph Truman and Mr. Truman were talking about it, and Ralph said, “Well, Harry, are you going to do it?” And Harry says, “If the son-of-a-bitch wants to see me, you tell him to come out here.” And by cracky, he did. He came. He made the extra mile,

25

and he came out to see Mr. Truman. Well, everybody was wondering what would happen when he came in. Well, they came in . . . Eisenhower was a little reserved, but Mr. Truman was very warm, very pleased. They went in the office, and they had a little private conversation. They came out, and it was like the old days. They were really very pleasant.

Then they started going through the museum, and they got about halfway through, and then finally the president turned around to the general and he said, “General, I’ve got a lot of work piled on my desk. Besides, we’re going to get together tonight. I’m going to turn you over to Perry. He’s my curator here, and he’ll take you through.” And so President Eisenhower smiled and so forth. Then, as Mr. Truman was leaving, he had this grin as he walked by me, and he said, “Perry, after he leaves, be sure to count the silver,” and just walked right on, you know, with that real grin and those mischievous eyes, you see.

And then the general came over and said, “I’m glad to see you here. I’m glad to see you’re working here.” He said, “You know, they’re going to build a museum for me up there.” Is that the end of a tape? He said, “You know they’re going to build a library and museum for me over there in Abilene, and I hope that you’ll be involved in that.” And then we had a very nice tour of it.

And, oh, not long after that, Sam Rayburn died. So Mr. Truman and Eisenhower both were there, and got along very, very well. And then, at Jack Kennedy’s funeral, I mean, they stayed in the same house and went out together, and they got back very, very well. I mean, they just cemented things up really very nice. It was nice to see because they had been old 26

friends, they had really admired one another, and I thought it was very warming to see them get back together after all that problem.

But I don’t think he ever really forgave Eisenhower, because, you know, he had George Marshall on a pedestal, Truman did. He thought he was a very remarkable man. He used to love to tell that story when World War II began and Marshall was chief of staff and Mr. Truman wanted to be called up . . . [telephone rings] I’d better catch that. [tape turned off] . . . to get back together, because they really were, I think, good men, and I think they both did have admiration for one another.

WILLIAMS: You said something about Washington.

PERRY: Pardon?

WILLIAMS: You said something about Washington, and that had irritated Truman.

PERRY: I’ve forgot now. I don’t remember what I was talking about that irritated . . . You mean Eisenhower in Washington?

WILLIAMS: As president in Washington.

PERRY: Oh, no, I know what it was now. When World War II began and Marshall was chief of staff—that’s what it was. Mr. Truman loved to tell the story about how he tried to be called up in active duty in the artillery, in the reserves, and they wouldn’t let him do it. And he went in and saw General Marshall and said, “Why can’t I do it?” And he says, “The general pulled his glasses down and looked at me and said, ‘Senator, you’re too damned old.’” And he says, "But general, you’re older than I am.” “Senator, that doesn’t make a damn bit of difference. I’m chief of staff and you’re not.” He used to love to tell that story. [laughter] So he never got called up in active duty.

27

And then his cousin Ralph got in a mess with the 35th Division. He was trained in the 35th Division. They were on maneuvers in Louisiana and Arkansas, and he got mixed up in the famous “Yoo-hoo Incident,” which happened in 1940 when people were training and people were very, very possessive about their boys just being called back into military service. Anyway, a bunch of these guys were on some trucks going down the road. They went by a golf course, and there were some girls playing in shorts, and so they started whistling and shouting at the girls. An old man in shorts was playing golf, too, and they kind of teased him. It turned out this was General Ben Lear, who was the commander of the whole Army and stuff. He got very upset about it and made a real big thing about it. Some of those guys, they threatened them with court martial, if I remember. Anyway, General Truman was relieved and was sent to recruiting duty and stayed in recruiting duty for the rest of the war. He was not in active duty. But it made Harry Truman furious, and he refused to vote for Ben Lear to get his fourth star, and I guess it destroyed the man’s career. He never got any higher than that. But it was a very nasty incident. You had an old Army general who didn’t understand civilian soldiers is what it was, but he never forgot that at all.

But he could read people very well. People would come in to see him, and a lot of times he would call me because he would talk with them and have his picture taken, then turn to me and say, “Perry will take you on a tour of the museum.” And I did that with countless people—well-known people, unknowns, and all that.

I remember one time, which I thought took a lot of courage, what they called the maidens of Hiroshima, who were girls disfigured by the 28

atomic bomb, had been over here for some medical treatment, and so they had stopped in the library to see him. So they were in the auditorium, and I went to see him, and I said, “Do you think you ought to see them?” He said, “Sure, I’m going to see them.” I said, “Well, they may not be friendly.” He said, “I can’t help it. It’s tragic, but I’m going to see them.” So he went out there, and the mayor of Hiroshima was there. And you know how the Japanese are, they were polite and bowing and things, and they all came up and he met them, and some of them were terribly disfigured. So then the mayor made a statement and so forth, and then one of the people said, “How could you do this to us?” And he almost had tears in his eyes, and he said, “You know, I have to look at it this way: If your country had never bombed Pearl Harbor, this would not have been necessary.” And as Japanese do, they were not . . . they didn’t confront him or anything. They smiled, and they bowed. And he walked out, and he shook his head and was in tears. He said, “You know, war is so terrible. They’re victims of war, no matter who they are. It’s awful. But,” he said, “I had to do it, and I’d do it again if I had to. Because I think it stopped the war, and I think it saved the lives of millions of people.”

And he firmly believed that the decision to drop the atom bombs ended World War II. Because he said that the projection had been that the invasion would cost at least a half a million American lives, plus unknown of Japanese, and if the Japanese had fought for their home islands like they did for Okinawa, the casualties would have been huge. And he said, “Here it’s like having the biggest gun that ends the war. The side that has it will do it to end the war.” He said, “And if they had it, they would have used

29

it.” So he was firmly convinced that that was the right decision. He never wavered from that for one minute.

WILLIAMS: Were you there when President Johnson visited?

PERRY: Yes, several times. Johnson, see, they were old friends. In fact, you know, Lyndon was sitting around striking a blow for the union when Roosevelt died. They were all in Sam Rayburn’s . . . There was a cubicle behind Sam Rayburn’s office in the house, and after business a bunch of them would get together, and Sam Rayburn would pull out the bourbon, and they’d all “strike a blow for liberty,” is what they called it, if I remember right. And Truman was there, and Sam Rayburn was there, and Johnson was there, and a whole bunch of them. So Johnson was one of the inside people.

And he was there when Sam Rayburn said, “Oh, by the way, Harry, the White House has been trying to reach you,” and he said,

“Call . . .” I think it was Steve Early. So he called, and he said, “Get to the White House right away, and don’t use the front entrance.” So he said he went around through back doors in the Capitol to his chauffeur. I guess he got a chauffeur or something who took him over there. And they ushered him in, and he said Mrs. Roosevelt was there, and she said, “Harry, I’ve got terrible news for you. The president’s just died.” And he said, “I’ll never forget what she said, because I said, ‘Well, Mrs. Roosevelt, what can I do for you?’ And she says, ‘You’re the one that’s in trouble now. What can we do for you?’” And he said, “I never forgot that.” That really made an impression on him.

But Lyndon was one of those groups. And when he came over as vice president, he would come in there, and it was everybody in sight,

30

every guard, every maintenance man, every secretary, “Howdy! I’m Lyndon Johnson”—pressing the flesh, he called it, all the way around. And even when he was president he had to do it, and he drove the Secret Service guys crazy because he was always jumping off and going in the crowd. He just loved people, hands on him, shaking hands. He just loved people. And I knew the Secret Service men. Well, he just drove them crazy.

But he and Truman liked each other a great deal. Truman liked Jack Kennedy but not the way he liked Lyndon Johnson. Lyndon Johnson was a man of the soil, and so was Harry Truman. Jack Kennedy was an Irishman, Boston Irish, that political field. They didn’t have that much in common. But he and Lyndon understood each other very much, and so Johnson came over to the library a number of times. And, of course, he saw him whenever he had a chance in Washington. They liked one another very much.

Now, Kennedy was smart, though, in that even though he and Mr. Truman were not that close, Kennedy made it a point to constantly keep in touch whenever major decisions were made, by phone, and asked his suggestions and advice, even though he might not have used it. But it pleased Mr. Truman because he would say, “Well, the president called me today asking about so and so and so and so.” And I remember when the Bay of Pigs came up. I think it was on a Saturday, and he and I were in the library when the call came. And he talked and looked very grim, and he said, “Well, if you’ve ever prayed, you better start praying today.” He said, “I can’t tell you what it’s about, but you better start praying. Because,” he said, “if what could happen could happen, it could be a terrible thing for all

31

of us.” Well, that was when they declared the blockade and stopped any of the Soviet ships, you see. But he was very pleased that the president would call him. And I’ve known people on Kennedy’s staff who said, yes, he did it to Eisenhower, too. Well, it was smart. But Mr. Truman liked that.

But Johnson really was genuinely wanting to know what Mr. Truman thought, and they would actually discuss things because they could do it. They had this relationship from way back. So I think his input with Johnson was a lot more than with Kennedy.

WILLIAMS: And you mentioned Nixon earlier. Could you elaborate on Mr. Truman’s feelings for him?

PERRY: [chuckling] Yeah. Well, I told you that he hated him because he said he called him a traitor. And when Nixon was elected, that really got Mr. Truman. He was not very pleased with that at all. But the funny thing was, no sooner had Nixon gotten in the White House, we started getting all these overtures from the White House. The curator of the White House is a very close friend of mine. He started calling him when he got in and said, “The president has found an old piano in the living quarters of the White House. He asked me did Mr. Truman play it, and I said yes. He ordered me to send it out to the library.” And he says, “I said I couldn’t tell him that he can’t give it, that it belongs to the White House. He doesn’t have the power to give it away. But anyway, he’s determined to see that it goes to the library. I think he wants to come with it.”

Well, first thing you know, we get inquiries from the White House staff about “the president has a speech in Kansas City and would like to come by and present a piano to President Truman. Would President Truman accept it?” Well, we talked to him, and by that time he was

32

slowing down a whole lot and didn’t come to work that often. But anyway, we talked with him about it, and he said, “Well . . .” He admired the office of the presidency, and even though he hated the man in the office, he admired the office. So he said yes, he would do that. So they shipped this battered-up, beat-up piano in there. It’s got water stains on it, [chuckling] and beer stains probably, everything else, and they shipped this thing in. And then here comes the President and Mrs. Nixon. So they have it in the anteroom of his office, and Mr. Nixon comes in and makes this nice speech presenting the piano, and Mr. Truman makes a nice speech in return.

And Mr. Nixon, with this big grin says, “I have something to show you. You’re not the only piano player to ever live in the White House.” Then he sat down and he played a song, and it was the “Missouri Waltz,” which Harry Truman hated. Because he said, “Do you know why I hate that song?” I said, “Why?” He said, “If you had heard it fifty-six times in one day, every time you’d go on a whistle stop and stop and they’d play it, you’d get tired of it, too.” The one he loved to play was called the “Black Hawk Waltz,” which was a song he said Abraham Lincoln liked. But he played that. I never heard him play the “Missouri Waltz.”

Anyway, Mr. Nixon sat down and played the “Missouri Waltz,” and he was terrible. I mean, you could see that he’d learned it just for this. But after it was over, Mr. Truman very graciously thanked him and all of that. And then Mr. Nixon was smiling and the cameras were on and stuff. And then Mr. Truman turned around, and by that time his hearing was not very good and his hearing aid wasn’t turned on very well, because he said, “Bess, what did he play?” And you could hear it all over the place, you know? But Mr. Nixon acted like he didn’t hear it.

33

But anyway he did make the gesture, but that didn’t change Mr. Truman’s mind on Mr. Nixon, because he just detested that man. And I was always glad that he died before Watergate. I mean, even though he hated Nixon, he would have hated to see the office of the presidency maligned. That would have just broken his heart to see that anyone could do that with that office, because he revered the office of the presidency. It was something like holy to him, and he would have just hated to see that done to it.

WILLIAMS: Do you think Nixon knew Truman’s feelings?

PERRY: Oh, yes. Oh, Mr. Truman made no bones about it. But see, I think Mr. Nixon . . . I mean, he respected the office too, and I think he felt that, now that I’m a president and he’s a president, we should put these personal things beside us. Which they did, which I thought was nice that they were able to do that. Even though Mr. Truman didn’t like him individually, he respected him for being president, and I think probably would have approved . . . I never talked to him about it because by that time he wasn’t coming to the library very much. I don’t know if he approved of some of the things Mr. Nixon did, but I think foreign policy things, especially like opening China and things like that, I think he would have probably approved of that because he liked dynamic foreign policy. And Nixon was good in foreign policy. That was his strong point. And I think the president would have appreciated that.

[End #4335; Begin #4336]

WILLIAMS: Well, we were talking a little bit before and just now about Mr. Truman as a historian. Could you elaborate a little bit more on that?

34

PERRY: Well, of course, he never got to college. He wanted to desperately. First of all, his family couldn’t pay [for] him, so he tried to get an appointment at West Point and couldn’t do it because of his eyes. He claims he had what he called flat eyeballs, and he swore up and down that his prescription on his glasses when he was seventy years old was the same as when he was seven. And he also loved to tell the story about when they would play baseball and he would say . . . I’ve heard him say many times, “I could not see well enough to be a batter or a fielder, so they always made me the umpire.” And he’d just laugh about that. He just loved that story. [telephone rings] Whoops! I’d better grab that if I can. [tape turned off] No, he wanted to go to college. He loved history, and he understood history, because I think he became president with more knowledge of former presidents than any president we ever had. Because he read biographies, he could tell you things about former presidents that he’d learned in reading, how they approached the office, how they approached decisions, what their history was. He was so good about that. Well, I’ll tell you, when the man that helped him do his memoirs over at KU—I’ve forgotten the doctor’s name now, but anyway he helped put it together—he said, “You know, I only found one error in thousands and thousands of pages of writing and dictation, and that was the date of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.” Can you believe that? But he swore up and down that that was really the [only] error that Mr. Truman made when he was talking about some of the history of the country.

And he grasped history. He grasped the importance of it. He used to love to talk with youngsters and said, “You know, if the history of the country is what you have to read, then there’s really nothing new except the 35

history you haven’t read.” And he believed that. And he said that when he would make decisions he would think of former presidents, other presidents when they had their moment of decision, and he would compare it to them and how they arrived at decisions. And he took great comfort in that.

One of the things he never did do, and I wish he had, he said, “I want to write a history of the United States for high school youngsters,” he said, “because they do not get the history of the country as they should.” And that was one of the things he kept saying “I’m going to do,” and he never did. Now, whether in any of his papers there’s unfinished chapters or things where he started, I don’t know. Do you know whether there is such a thing?

WILLIAMS: I think part of that book that Margaret put out years ago was some of that.

PERRY: She may have used some of it. Might have been true.

WILLIAMS: Where the Buck Stops, or whatever.

PERRY: Right. Might have been true. But he used to talk about that over and over, and he said, “That’s one of the things I want to do.”

WILLIAMS: Was he involved in the Jackson County Historical Society?

PERRY: Very much. When we revived it, Rufus Burrus had been a former president some years before, and then Howard Adams became the new president. And so they talked to him, and they decided they’d like to save that old jail and marshal’s house on the square. Well, that delighted him because he said to me one time, he said, “You know, when I was county judge, that was the best job in the county because you got a neat house to go with your job, and the rest of us didn’t get such a thing. So I had plenty of people who wanted that job.” And so when we set it up, what we did 36

was we had a battery of telephones installed in there, and they were going to call for solicitations. Well, the first call was Harry Truman calling Joyce Hall. I think he got $5,000, I believe, from that. Of course it was set up, but it was good for publicity. And then we had . . . when we finally got it done, we had the dedication. He was very proud about it because he felt that that building was part of the history of the city, of the frontier history, the history of old Independence, and he loved that. And so he was delighted that that happened. And Nile Miller, who at that time was the director of the Kansas State Historic Society, he came over and made a speech, and he delighted Mr. Truman by saying that, well, he was finally glad to see what the buildings looked like that they put the Kansans in who came over during the border wars. And when we built the museum in Lone Jack, I researched and built that, and he talked about how on . . . I think is it August the 19th? That was a day that they had a custom in those days that during the primary all the candidates in the county would go to Lone Jack for the picnic, and they would all get up and give speeches. And they don’t do that anymore, but when we were talking about building a museum there, he reminisced about how they’d all go out there and hear the speeches by the candidates. And of course he knew about the Battle of Lone Jack. Well, after I designed and installed the building and all, he got an invitation to come out there for the dedication, and he says . . . He called me in his office, and he said, “You built that, and I’m going to go out there and I’m going to dedicate it for you.” And I said, “Boy, I sure appreciate that.” And he did. He went out there and gave a real nice little talk about it, and he said, “Because I think you’ve done a fine thing for the county, and I want to show you my support.” So he hopped in his car and

37

went out there, which was really very nice. But he was very supportive of the society, allowed them to keep their records and things in the museum, the basement of the library, for several years, as a matter of fact. All the archives were down there.

WILLIAMS: How much did he reminisce about being on the farm out in Grandview?

PERRY: All the time. Oh, he just loved it. On those Saturday mornings he and I would coffee, we just . . . Because my grandmother was very similar, I guess, to his mother, and we used to compare notes about the way she cooked and how the food tasted, and him plowing and planting and going down to Grandview and catching the train, and listening to the election returns, and riding up and down those long rows looking at the south end of a mule going north—he loved to talk about that—and the rows would never end, and how hard it was . . . how hard it is to be a farmer, because you’re completely dependent on the weather, and how he never had much money and always seemed to be in debt. And then he would reminisce about how he would try . . . He tried various things to get out of it. You know, he had some oil wells one time, or leases on oil wells down in . . .

ODUM-SOPER: Eureka.

PERRY: Eureka, right. And he said later on that it hit one of the biggest fields around. If he’d just stayed on it, he’d be very wealthy. Then he tried to get some land, wasn’t it, in Idaho or someplace. I’ve forgotten where it was now. That didn’t work out. He tried all these various things that didn’t work out. And as he said, “I was a failure up until the time I was forty years old.” And he was. Just about everything he hit was a failure. It wasn’t until he went into politics, and he went through that in the back door 38

because he didn’t plan on being a politician, you know. It was Jim Pendergast, I think, talked him into it.

I know Edgar Hinde—I liked Edgar very much—and Edgar in those days had gotten him an automobile agency. Edgar said, “Boy, I was going to turn the world on. I had the car that was going to do it.” He said, “I sold Rickenbackers.” [laughter] And anyway, he said, “I’m on my back underneath a car, working on one, and Harry comes in and says, ‘Edgar, I’ve made a decision.’” He said, “I rolled out on that thing and looked up and said ‘What is that, Harry?’ He said, ‘I’m going to be a politician. I’m going into politics. What do you think of that?’ So I looked at him and said, ‘You’re crazy as hell. Why don’t you go out and work for a living?’ Then I rolled back under there and started working on my car again.” [chuckling]

But he knew local history. He knew the old citizens in town. He was proud of them. He knew the history as well as the gossip. One time I went to a meeting of the Harpie Club, which was the Harmoniconian Society, you know. They formed this organization, some of those veterans did, as an excuse to play poker and drink. They told the world they were practicing on the harmonica. And the guy, he and Dexter Perry and Edgar Hinde, and I’m trying to remember all of them up there, would get up there and they would drink. And they met up over on the . . . When I knew them, they met over on the east side of the square. There’s a corner building right next to the Bundschu store. There’s that building on the corner. It was up on the third floor when I was up there, I think, is where the Harpie Club met. I think they met all over town, but that’s where I went one time because Dexter Perry took me.

39

Now, Dexter Perry was an interesting man. I don’t know if they ever taped him or not, but he was a very close friend of the president’s. But Dexter was a man who was not ambitious. He loved life, loved living day-by-day, never married, never had much money, but he was just happy. And he would come in and see Mr. Truman. Because down-and-out veterans would go through him, and he’d go see Mr. Truman, and Mr. Truman would use his influence to help them out. And he told me one day, he said, “There goes a man who literally gave somebody the shirt off his back.” And I said, “What do you mean?” He said, “Well, when I was county judge, [Dexter] had this fellow came in and said that he was broke, didn’t have a job, didn’t have any money, had a family to support. Was there any kind of a job he could find? So Dexter called me up, told me who he was. So I called Ed Hinde, who ran the park department, except there wasn’t any parks. What they did was they cleaned ditches and cut grass along the highways. And I asked Edgar if he could use this man, and he said, ‘Well, send him over.’ So I called Dexter. So what Dexter did, Dexter had a little office with a little wash basin in it. He said the man looked terrible, so Dexter said, ‘Well, you can’t go apply like this.’ So he made him take his shirt off and made him wash and loaned him his razor, and he shaved. And he said, ‘Now, is that the only shirt you’ve got?’ And he said, ‘Yes, it is.’ So Dexter took his shirt off and gave it to the guy, and the guy went and applied for the job.” And Truman thought that was a great, wonderful gesture of a man who would literally give another man the shirt off his back. And he loved Dexter. And then when Dexter died we all went to that funeral, and he was very, very shook-up.

40

But I think the person he loved the most as an individual, besides Bess, was Ralph Truman. He thought the world of Ralph Truman. I did, too. Ralph was straight as a ramrod, could be very abrupt, had been in the Spanish-American War and World War I, and then of course I told you about his World War II business, and then had been for years working for a fire insurance company investigating fire insurance. But he was one of his primary political advisors, especially when he was a senator. And Ralph used to love to tell the story about in the 1940 election. He said, “I knew Harry was going to get his ass beat. He just didn’t have it. I knew he was going to get it beat. And so I figured out the best thing for that was we’d try to split the vote. And he talked about it, and he had all three candidates in the Meuhlebach Hotel, each on a different floor at the same time, running back and forth. He wanted to get all of them to run, but he didn’t let the other ones know that he was doing it.” He said, “I would go up and down the back stairs all night, talking with this one, then I’d go and talk to Harry, and then . . . Who was it? Lloyd Stark . . . I forgot who they were. Who ran in that, the three-way election?

ODUM-SOPER: Milligan.

PERRY: Milligan, that’s right. Milligan was one, Truman was the other, and Stark was the one, wasn’t he. And he got them all to run against each other. [chuckling] And the idea, of course, was Truman . . . And it worked, of course, which is what happened in 1948. But he said the first time he ever left Jackson County on a big trip was he and Ralph went to see Ralph’s dad. [telephone rings] I’m going to let it go right now. Went to see Ralph’s dad . . . You’re picking it up though, aren’t you. Wait a minute. I better catch it. [tape turned off] Are you ready?

41

WILLIAMS: Okay. How well did you know Bess Truman?

PERRY: I liked her very much. You know, she got a real bum press, because Mrs. Truman just wanted to be Bess Truman. She did not like the folderol in Washington. She did not like being on exhibit, and so she wanted to be a private citizen. And the press interpreted that as hostility and were not very kind to her. But actually she was very warm, she was very bubbly, she laughed a lot, a real lady. And she had an asset that every politician should have. They claim that she never forgot the name of anyone once she was introduced to them.

It’s interesting that Bess and Harry, the way they lived with her mother, it’s very interesting because her mother detested Harry. And yet he lived with her and in that house all that time, and yet Mrs. Wallace did not think of him at all, and yet she lived in the White House.

WILLIAMS: Did he ever talk about Mrs. Wallace?

PERRY: Not really. No, not really. I don’t know why he didn’t. I don’t know how he put up with it, because she didn’t treat him very nice. And the stories were that she wanted to know why he was running around saying dirty, nasty things about that nice Mr. Dewey, and she was living in the White House. But Bess herself was very friendly, and we knew her. She was very nice to the wives of the people that worked at the library. In fact, my first wife loved to read Erle Stanley Gardner mysteries, and Bess loved them, and Erle Stanley Gardner would send her all his books. As soon as Bess got through with them she’d loan them to Barbara. Then Barbara, she would pass them on to the next, and they did that. Or they’d go to the public library. And if Bess had read a book she liked, she’d call up my 42

wife and tell her so. Or my wife would call her up and recommend these books. They just shared that.

Now, she liked television, but he didn’t like it. He hardly ever watched television. One time this happened when the guy that played Ben Cartwright, Lorne Greene, came on a personal appearance tour, and he landed in a helicopter in the courtyard, and Mr. Truman went out to greet him. And Lorne Greene had thought he was a fan of the TV show, and he said, “Well, Hoss didn’t come with me.” Well, Hoss was his son on the television [show]. This big, Dan Blocker guy about seven feet tall, you know, a huge guy. He said, “He decided he couldn’t come today. He had something else to do or something.” Well, Mr. Truman didn’t watch the show. He thought he mentioned “horse.” He went over and looked at that helicopter, and he said, “Well, I don’t think you could have got one in there anyway.” [laughter]