Last updated: January 4, 2022

Article

Military Service and Family Concerns Reflected through Revolutionary War lieutenant buried at St. Paul's

National Park Service

Militia service & Family Concerns Reflected through Revolutionary War Lieutenant buried at St. Paul’s

William Pinckney, who is buried in the historic cemetery at St. Paul’s Church N.H.S., is representative of men from prominent local families who supported the American Revolution through service as officers in militia regiments, instead of the more daunting task of joining the Continental Army. Pinckney’s political odyssey during the war also reflects the complicated allegiances of residents of the St. Paul’s vicinity.

A descendant of one of the founders of the settlement, Pinckney was born in 1736 into comfortable circumstances in Eastchester, the parish of St. Paul’s Church, about 20 miles north of New York City. A military heritage comes through his uncle, William Pinckney, who earned community distinction by serving for many years as captain of the local militia company. Commission as an officer in the militia, in Eastchester and other colonial towns, was a traditional form of service and development of leadership among young men from notable families. It sanctioned and furthered their reputations, helping to achieve respect and contributing to the maintenance of order and stability. More a social and political activity than a military pursuit, monthly militia drills were festive gatherings of people on the village green in front of St. Paul’s Church. Militia companies could be trained more rigorously at times of urgency, such as the approach of the Revolutionary War.

William was 39 in 1775 when the political crisis between the colonies and England erupted into armed conflict following the initial fighting in Massachusetts. In September, as the county prepared for likely military action, the militia was reorganized on a more serious footing. Indicating support for the revolution, Pinckney was chosen as the ensign, one of five officers of the company; his older brother Thomas Pinckney was selected as first lieutenant. In the spring of 1776, on the eve of the large scale British invasion of New York, William was promoted to first lieutenant. St. Paul's gravestone of William Pinkney's uncle, Will Pinckney, Captain of the town militia, chalked for this 1930s photo.

Why didn’t he join the Continental Army? Some local, usually younger men took the extraordinary step of offering their services to the emerging national army under General George Washington. Enlisting in the Continental Army introduced a likelihood of deployment beyond the boundaries of the colony, in uncertain circumstances that were perhaps more hazardous. William was 40 by then, and he and his wife Freelove were raising 11 children. Additionally, the militia, rooted in tradition, probably seemed the more logical choice of service. It offered the familiarity of fighting with neighbors, under or at least alongside people of your choice, rather than the vagaries of a national, anonymous force. Besides, with major fighting about to commence in New York, militia service in the province would not have carried a stigma of avoidance of danger.

William participated in the mobilization of the spring of 1776 when Continental Army General Charles Lee summoned the company to assist with preparations for the protection of New York against the imminent British invasion. The Westchester County men erected defenses at Hell’s Gate, where the Harlem River joined the East River, near today’s Triborough Bridge. Most reports show the Westchester militia stationed in lower Manhattan by the summer of 1776 and assigned to Major General Israel Putnam’s command in the Battle of Brooklyn, fought in late August, the largest land battle of the Revolutionary War.

Following the New York campaign of 1776, Westchester militia units were on call or patrol in the difficult terrain of the “neutral ground” from 1777 through 1782. In that volatile period, the southern and central parts of the county were entangled in a no man’s land between the British and American armies. Local militia units were overwhelmed by British and Loyalists forces raiding into Westchester from Manhattan. Pinckney may have joined in some operations at that time.

One of the 19th century local histories mentions that William developed an allegiance to the Crown during the war, in contrast to Freelove’s continued support for the revolution. This was a plausible scenario; residents of lower New York shifted political allegiances over the course of the conflict, and preferences conflicted within families. More likely, William adopted a posture of neutrality to safeguard the family, a prudent move in 1780 when the British held strong positions in the Eastchester area. Unlike many landholding families, the Pinckneys never evacuated the town. They attempted to navigate the challenging circumstances of the neutral ground and remain on their farm during the war. Yet, those strategic decisions on loyalties failed to protect the family, symbolized by the Pinckney's militia regiment was present at the Battle of Brooklyn. death of one of his sons, Henry Pinckney, shot and killed by British troops at the home in early April 1780 -- a development almost suggesting a storyline of the cable television Revolutionary War series “Turn: Washington’s Spies”

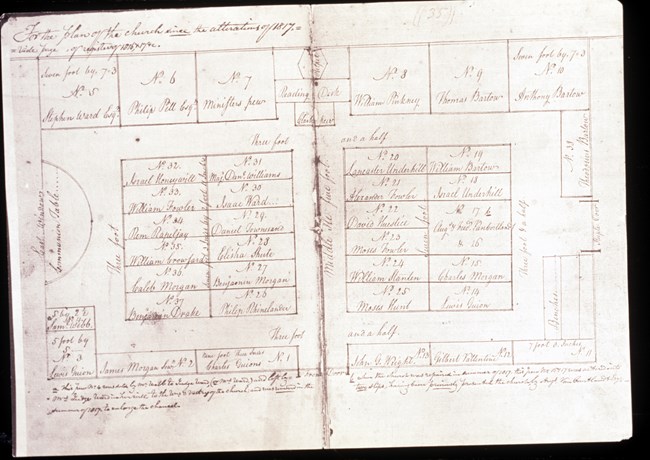

At the war’s conclusion William emerged as one of the local leaders who helped rebuild the community following the severe disruptions of the war, chiefly in his roles as commissioner and overseer of town roads from the late 1780s through the early 1800s. The 1790 census recorded ten people in the Pinckney household, including William and Freelove. In 1800, Pinckney’s estate was worth about $3,500, placing the family at the top tier of the town’s wealth. For the history of St. Paul’s, Pinckney’s prestige is preserved through the large pew he obtained in the initial distribution of boxes following the revolution. In 1787, the Pinckney family, with at least ten people, donated 23 shillings, one of the largest in the parish and sufficient to reserve a double pew to the immediate right of the pulpit. That location is reflected in the 1942 restoration of the church’s interior to the 18th century appearance, observed by today’s visitors to St. Paul’s. Pinckney also served in the mid 1790s on the vestry, the ruling council of St. Paul’s.

He died in 1802, followed by interment behind the church. Freelove outlived him by 20 years, followed by burial near her husband. Years later, in the early 20th century, descendants of William recognized his wartime militia service as the basis for admittance into heritage organizations preserving the Revolutionary War -- the Sons and Daughters of the American Revolution.