Part of a series of articles titled People of the California Trail.

Article

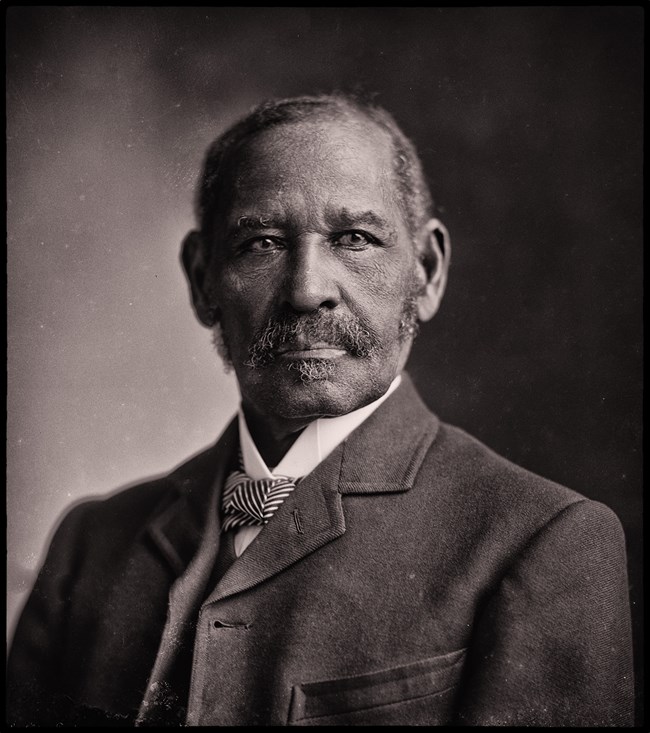

Mifflin W. Gibbs, the California Trail

Image/C.M. Bell Studio Collection (Library of Congress)

Mifflin W. Gibbs – California Trail

By Angela Reiniche[1]

“Fortune, in precarious mood, may sometimes smile on the inert, but she seldom fails to surrender to pluck, tenacity and perseverance.”

- Mifflin W. Gibbs

Gibbs, like so many thousands, left the East for San Francisco in 1850, convinced that his own “judicious temperament, untiring energy, lexicon of endeavor, in which there is no such word as ‘fail,’ [was] the only open sesame” to the opportunities that awaited him in the “new” country.[2] He may have been a “gold rusher,” but Gibbs had no interest in becoming a miner. And, as a free Black man, he had no need to buy his freedom with mining-camp labor. Instead, Gibbs intended to secure his financial future as a merchant.

Born in Philadelphia in 1823, Gibbs apprenticed as a carpenter; by the early 1840s, he was also active in the abolitionist movement. He was a devoted follower of Frederick Douglass, earning a reputation as an orator and writer; he also aided those escaping to freedom via the Underground Railroad. He eventually made his way to California by sea, becoming a pillar of San Francisco’s African American community, finding success as a merchant, founding a newspaper, and continuing to organize for the rights of Black Californians and enslaved people. Gibbs wrote that, while free Black Californians could find economic opportunity, “from every other point of view…they were ostracized, assaulted without redress, disfranchised and denied their oath in a court of justice.”[3]

Gibbs’ steamship voyage to California was generally much less perilous than overland routes like the California Trail. Although briefly detained by illness in the “surprisingly cosmopolitan” Panama, Gibbs disembarked at the port of San Francisco in September 1850. Gibbs’ first stop was “an unprepossessing hotel kept by a colored man on Kearny Street” where “seated at tables, well supplied with piles of gold and silver, were numerous disciples of that ancient trickster Pharoah.”[4] Nearly penniless, Gibbs learned that he was to pay for his board in advance. (Gibbs had only fifty cents in his pocket after buying a ten-cent cigar at the hotel bar.) He immediately went looking for work, plying his skills as a carpenter. Yet even when a contractor did hire him, Gibbs did not last long on the job because “white people would go on strike the day [he] started” and the boss would tell him to leave.[5]

He left the carpentry trade behind and got into “blacking boots,” spent time working for John C. Frémont, and joined a firm established in the clothing business. Not long after, he and another African American, Peter Lester, founded the Pioneer Boot and Shoe Emporium. The business partners found economic success importing “fine boots and shoes” to their storefront on Clay Street. Their store had a reputation for “keeping the finest [goods] in the State, [and] was well patronized, our patrons extending to Oregon and lower California.”[6] Yet despite the modicum of legal and economic freedom African Americans had achieved in the state, Gibbs grew frustrated by the lack of legal protections afforded to Black Californians. In his autobiography, he recalls an “incident typical of the condition” in which two of the shop’s white customers, who happened to be friends, were caught trying to dupe the bootsellers. When called out for their attempted thievery, the two men hurled “vile epithets” and “using a heavy cane, again and again” assaulted Gibbs’s partner, who was “compelled tamely to submit, for had he raised his hand he would have been shot, and no redress.”[7] Gibbs was also helpless to resist, as he knew the law would prevent him from testifying against Lester’s assailants. In 1854, Gibbs joined forces with other Black San Franciscans and established a civil rights organization; he also led the publication of the Mirror of the Times, “the first periodical issued in the State for the advocacy of equal rights for all Americans.”[8] In the years that followed, Gibbs and the growing Black intelligentsia of San Francisco organized for African American rights, often raising the funds to hire attorneys to represent their community members in court.

Tenacious in the pursuit of fortune as well as justice, Gibbs left California in 1858 after the discovery of gold on the Fraser River in British Columbia, joining the migration of many African Americans from California into present-day Canada. He and Peter Lester re-established their business ventures among the miners that had flooded the surrounding area. Once again, Gibbs prospered as a merchant; he was also elected to the Victoria City Council. At some point in 1859, he traveled back to the United States to marry Maria Alexander, a student at Oberlin College in Ohio. Back in Victoria, Gibbs studied law with a barrister who eventually convinced him to return, yet again, to the U.S.—this time to attend Oberlin College, where he earned his law degree. He and Maria had five children before they separated in the late 1860s. After that he returned to Canada and developed an anthracite coal mine on the Queen Charlotte Islands, secured the contract to build British Columbia’s first railroad, and continued to advocate for the Black community.[9]

Gibbs later settled in Little Rock, Arkansas, where he practiced law. He was appointed the Pulaski County Attorney during the Reconstruction era and, in 1873, was elected city judge of Little Rock. He held prominent leadership roles in the Republican Party, and President McKinley appointed him to a four-year-term as consul to Madagascar at the age of 74. He resigned the post four years later for health reasons, returning to the U.S. and publishing his autobiography in 1902 (with an introduction written by Booker T. Washington). Although Gibbs never traveled the California Trail, he remained a pillar of the Black community at the trail’s western end—and beyond.[10]

[1] Part of a 2016–2018 collaborative project of the National Trails- National Park Service and the University of New Mexico’s Department of History, “Student Experience in National Trails Historic Research: Vignettes Project” [Colorado Plateau Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit (CPCESU), Task Agreement P16AC00957]. This project was formulated to provide trail partners and the general public with useful biographies of less-studied trail figures—particularly African Americans, Hispanics, American Indians, women, and children.

[2] Gibbs, Mifflin Wistar. Shadow and Light: An Autobiography with Reminiscences of the Last and Present Century (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1995), 37.

[3] Ibid., 45–46.

[4] Ibid., 40.

[5] Ibid., 43.

[6] Ibid., 45.

[7] Ibid., 46.

[8] Ibid., 48.

[9] Ibid., ix, xi, 59, 64, 108, 111.

[10] Ibid., 136, 155, 223. For more on Gibbs, see Katz, William Loren. The Black West: A Documentary and Pictorial History of the African American Role in the Westward Expansion of the United States. New York: Harlem Moon/Broadway Books, 2005; Katz, William Loren. Black People Who Made the Old West. 1st Africa World Press Inc. Ed. ed. Trenton, N.J.: Africa World Press, 1992; Crawford, Kilian. “Mifflin Wistar Gibbs (1823-1915),” Blackpast.org. Accessed 22 September 2017. http://www.blackpast.org/aaw/gibbs-mifflin-wistar-1823-1915; Crawford Kilian, Go Do Some Great Thing: The Black Pioneers of British Columbia (Vancouver BC: Douglas & McIntyre, 1978); and Dillard, Tom W. “The Black Moses of the West: A Biography of Mifflin Wistar Gibbs, 1823-1915.” M.A. Thesis, University of Arkansas, 1975.

Last updated: March 9, 2023