Last updated: September 22, 2022

Article

"One of the liveliest and most exciting times we had ever experienced": The Battle of Middleburg and the Fight at Goose Creek Bridge

Library of Congress

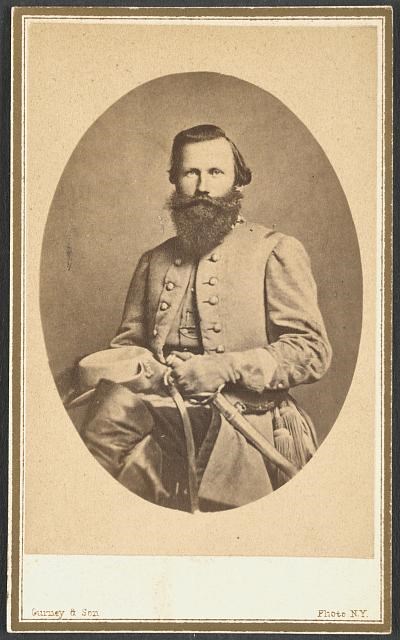

The fighting on June 19, 1863, at Middleburg, Virginia, and the movements of Major General J.E.B. Stuart’s Confederate cavalry during the following day, led Army of the Potomac cavalry commander, Major General Alfred Pleasonton, to believe that Stuart’s cavalry was supported by infantry. Because of this, Pleasonton requested infantry to support his mounted command. The request was approved, and orders were filtered down the chain of command. The assignment fell to Brigadier General James Barnes’s division of the Federal Fifth Corps, which was marched toward Middleburg. The scene was now set for yet another day of fighting in the Loudoun Valley all due to the Army of the Potomac’s push to gather intelligence on the movements and intentions of the Army of Northern Virginia.

The week of largely cavalry engagements in the Loudoun Valley during the middle of June 1863 are often overlooked due to the many other events that transpired during that fateful summer. This can also be said of the Gettysburg campaign itself, as a few moments from the campaign have become a fixture in the popular historical lexicon at the expense of others. It was only after years of hard work by historians and preservationists that the story at Brandy Station on June 9, 1863 entered into accounts of the campaign. And further overshadowing events of the campaign was the battle that resulted. Over July 1-3, 1863 numerous actions across two large fronts of battle took place. Yet, due to many influences over the intervening 157 years some were forgotten while others became entrenched in popular memory.

For many, the story of Gettysburg is a meeting engagement on July 1, Little Round Top on July 2, and Pickett’s Charge on July 3, 1863. Even within the microcosm of Little Round Top, these same principles hold true. Certain units and actions have been pushed to the forefront of historical memory while others have been forgotten. At Little Round Top, Colonel Strong Vincent’s brigade of Federal soldiers, including the 20th Maine Volunteer Infantry, have for decades received the lion’s share of ink in the telling and retelling of that moment of battle on July 2. But the heroic stand of Colonel Joshua Chamberlain of the 20th Maine and the other units of Vincent’s brigade, was not their first combat experience during the Gettysburg campaign. Their first action during the campaign was just outside of Middleburg, at Goose Creek on June 21, 1863.

Library of Congress

“On the morning of the 21st, before daylight, we were aroused from our slumbers and ordered to move towards Middleburg in support of the cavalry, which was expected to attack the rebel cavalry force on that day,” wrote A.M. Judson, regimental historian of the 83rd Pennsylvania.[1] Another soldier in Vincent’s brigade, a sergeant in the 16th Michigan, also remembered an early start to the day. “At 1 o’clock a.m. the bugle sounds to arms and up we get on the double quick. We cook our coffee, pack our knapsacks and leave them in charge of a guard….”[2] With the infantry brigade on the march towards the Union cavalry position at and just beyond Middleburg, a plan of attack that utilized them in the coming push westward was in the works.Upon ordering infantry support to Pleasonton’s assistance on June 21, Hooker created a plan of attack that utilized both the infantry and cavalry. Vincent’s brigade would be sent westward from Middleburg south of the Ashby’s Gap Turnpike, while Col. John Gregg’s cavalry brigade moved down the pike itself. Additional cavalry units under the command of Brigadier General John Buford were to be sent north as a flanking column. The remainder of Buford’s command not in the flanking column would remain behind as a reserve for the attacking force.

It was a long march before Vincent’s men arrived in support. Major Holman S. Melcher, 20th Maine Infantry, recorded that the brigade was put in “light marching order,” before “passing through Kittoctan [Catoctin] mountains at Aldie. March to Middleburg 6 miles and one mile beyond.”[3] Between 7:00 and 8:00 am, Vincent’s brigade arrived on the field. They were ordered into line with the rest of the Federal cavalry already in position. It was not long after their arrival that Stuart’s artillery opened on the growing Federal line. Lewis T. Nunnelee, a gunner in Stuart’s horse artillery, wrote in his diary of the opening of the battle that morning. “At 7 a.m. cannonading was heard in front which was being carried on by Hart’s Battery and the enemy….As soon as they made their appearance on the opposite heights we opened fire on them,” wrote the 42-year- old pre-war dry goods worker.[4] Stuart’s artillery continued to shell the line. Although the Federal units were not taking heavy casualties, the fire was unnerving to say the least. A correspondent from The New York Herald overheard Vincent’s orders to his men regarding the battery to “Stop that damn battery from howling.”

Vincent’s brigade had their orders. They were to move their line of battle forward, or westward, south of Ashby’s Gap Turnpike to turn the Confederate position. Their advance took them across the Bittersweet Farm and straight towards the position of Brig. Gen. Wade Hampton’s Confederate cavalry. A.M. Judson of the 83rd Pennsylvania recalled the movement of the brigade.

"Between seven and eight o’clock General Pleasanton sent orders to Col. Vincent to advance at least one regiment of infantry and dislodge the enemy’s carbineers from one of the stone walls in front. The Sixteenth Michigan...was accordingly directed to press forward and carry out the order. At the same time Col. Vincent sent forward the Forty-Fourth...and the Twentieth Maine...with directions to press the enemy hard and pick off the gunners from his battery".[5]

Although three regiments of Vincent’s brigade pressed forward against the Confederate position, one was not. The 83rd Pennsylvania was sent on a far flanking movement against the Confederate right, anchored by the 1st North Carolina Cavalry. “The Eighty-Third...was directed to move rapidly through the woods, to our left, keeping [our] force concealed, and the instant [we] had passed the stone walls to merge and take the enemy in flank and rear,” wrote Judson.[6] Pleasonton’s request for infantry had paid off. Hampton’s brigade pulled out after the flanking movement by the 83rd and Robertson’s brigade, north of the turnpike on Battle Knoll, also pulled back. Judson wrote triumphantly in the regimental history of the 83rd, “The movement was entirely successful. Finding their position turned, the enemy fled in confusion, and the Sixteenth advanced on the double quick, on the right, and compelled them to abandon one piece of artillery, a fine Blakely gun.”[7] Judson was correct about the capture of the gun by the 16th Michigan, later claimed to have been accomplished by Federal cavalry in the field. Some accounts placed Lt T. Frank Powers and Sgt. John Kuehn, Company A, 16th Michigan as the first Federal soldiers to reach the captured gun.

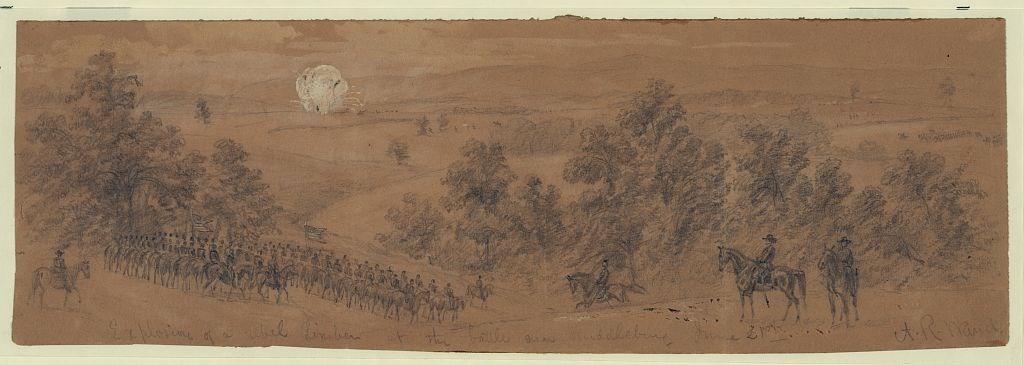

infantry under Colonel Strong Vincent and Union Cavalry under Judson

Kilpatrick at Goose Creek Bridge on June 21, 1863.

Library of Congress

With Stuart’s cavalry pulling back, one issue of his defensive position quickly became apparent. To get to his fallback positions further westward, the Confederate cavalry had to cross two bridges over two waterways. The first was a small bridge over Cromwell’s Run and the second, further west, a stone bridge over Goose Creek. Both of these bridges were along the Ashby’s Gap Turnpike. To ensure that he had enough time to get his men across these spans, Stuart ordered Wade Hampton’s 1st South Carolina Cavalry, Colonel John Black commanding, to push forward, slow down the Federal push, and act as a rear guard for Stuart’s withdrawal. It was a daunting task that Black and his men performed ably. While Black and his men labored in their hot work, Stuart created a new defensive position west of the stone bridge over Goose Creek. It was a strong line, set up along a significant height overlooking the bridge and creek. When the Federal assaulting force finally arrived at Stuart's new position, their attack stalled as they saw the strength of the opposing line.

A.M. Judson recalled Stuart’s new position in the regimental history of the 83rd Pennsylvania. “The enemy were posted behind two stone walls; one at the foot of the hill, a few rods beyond the bridge, and the other at the top and almost concealed by the tall growth of wheat through which it ran.”[8] Alfred Pleasonton and Judson Kilpatrick paused to come up with a new plan of attack, taking into consideration the challenges of Stuart’s new line. While they did so, Federal and Confederate artillery traded shots once more. Minutes ticked by. After nearly an hour of cannonading, and no signs of a forward push by Kilpatrick and Vincent’s forces, Stuart sent orders for his other units to fall back toward Ashby’s Gap. These far-flung units would meet towards the village of Upperville. Stuart was not the only one looking at Upperville, however. During the most recent lull in the battle, Pleasonton had finally settled on a plan to move forward. If Kilpatrick could push his men across the bridge, and Buford’s troopers could swing southward from their positions to the north, the Federal cavalry could unite at Upperville before pushing into Ashby’s Gap. These orders are quickly sent out.

The first attempt by Kilpatrick to take the bridge by cavalry alone was sent reeling backward with no success. The next attempt combined a frontal assault across the bridge, consisting of the 2nd New York Cavalry and the 16th Michigan Volunteer Infantry, with the remainder of Kilpatrick’s and Vincent’s men to attack across the creek wherever they could get across. One writer noted the excitement of the moment the orders were received, and Vincent’s brigade went into the fight. “Now happened one of the liveliest and most exciting times we had ever experienced: we were carried along, as it were, by the very tempest, whirlwind and, I might say, joy of battle into the midst of the enemy’s ranks.”[9] The action was quick. “As a bound the skirmishers of the Sixteenth, followed by those of the Eighty-Third, dashed over the bridge with a general yell, and shouting ‘Shoot them!’ ‘Take them prisoners!” rushed up the hill, drove them from behind the walls and again put them to flight, taking a number of prisoners, both officers and men,” wrote Judson.[10] Once again, Stuart’s line, under pressure from front and flank, was ordered to pull out from his position.

NPS Photo

The continual falling back told on the men in Stuart's ranks. An artillerist in Stuart’s Horse Artillery later recalled, “We were all disgusted and more or less demoralized from having to practically run about eleven miles the same day from the infernal devils. Such a thing had never occurred before and wouldn’t have this time if their forces hadn’t been combined and so many of them.”[11] Not only was there a collective feeling of low morale after a day spent constantly falling back, but there was a fear of the loss of their vaunted reputation. Lewis Nunnelee wrote simply, “Our disorderly retreat will give the enemy cause for a grand flourish of trumpets. As Genl. J.E.B. Stuart was personally in command today, he will have to look to his laurels in the future.”[12]

With Stuart’s most recent orders, the Federal attacking force was once again on the move. More fighting took place along Trappe Road and Vineyard Hill near Upperville later that day. Vincent’s brigade, however, was beyond spent. The combination of marching and fighting at the pace of the cavalry, all the while during intense summer heat, had pushed the brigade to exhaustion. “Altogether, our brigade was mainly instrumental in driving the enemy six miles from their original position; and we kept on, following them until we came in sight of Upperville, near Ashbys Gap. In doing this we had travelled (together with the morning’s march and the detours made in turning the enemy’s positions) nearly twenty miles; our men were too much fatigued to follow any further, and it was deemed advisable to halt and leave the pursuit to the cavalry,” Judson recalled. They were ordered back towards Middleburg. Their first battle of the campaign was over. Other additional Federal infantry was brought up to take their place.

Today, the action at Goose Creek Bridge is largely overlooked, both by academics and the public at large. Most campaign histories in the historiography give the all-day fight of June 21, 1863 just several pages with even lesser ink spent on the actions at Goose Creek Bridge. Further, the number of visitors to the location of this battle are also few, although the local traffic that zooms by the turn off towards the bridge and Civil War Trails marker remains constant. Yet, in stark contrast, Vincent’s brigade at Gettysburg, and especially their action at Little Round Top, have received numerous works in historiography. Whole books have been written on Chamberlain, Vincent, Rice, O’Rourke, Hazlett, and the other heroes of the successful Union defense of their position on July 2, 1863. Furthermore, Little Round Top remains one of the most visited areas on the battlefield today. But, for the men of Vincent’s brigade, weeks before their moment in history at Gettysburg, they had “one of the liveliest and most exciting times we had ever experienced” during their fight at Middleburg and Goose Creek Bridge on June 21, 1863.