Last updated: September 27, 2022

Article

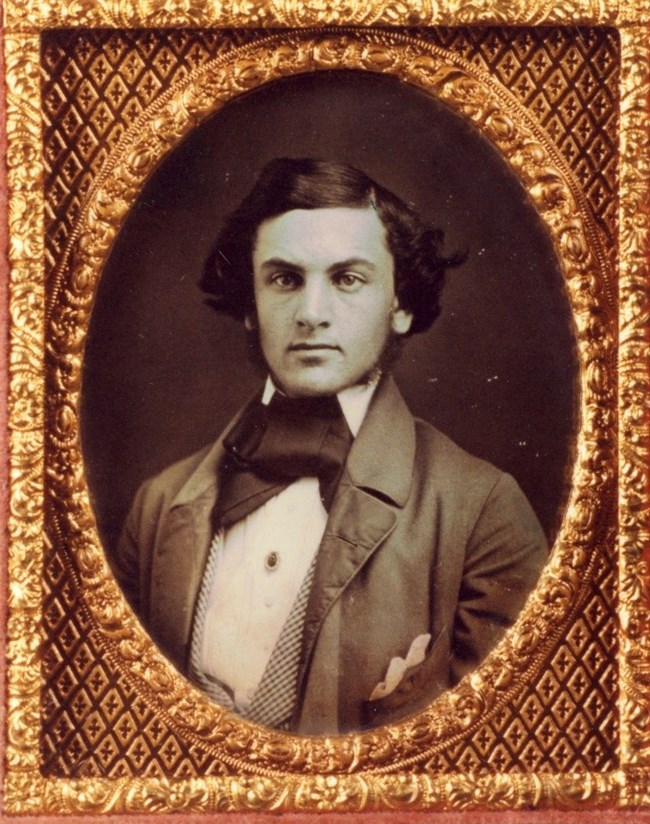

The Memory of Strong Vincent

Courtesy of the Hagen History Center in Erie, Pennsylvania.

When one hears the name “Strong Vincent,” association is often (and correctly so) made with the desperate fight of a brigade destined to claim the life of one promising 26-year old on the slopes of Little Round Top on July 2nd, 1863.

Prior to the outbreak of hostilities, however, the Vincent’s, lately of Waterford, Pennsylvania, were a long-established family, with traceable Puritan roots ranging back to the family’s first landing in Massachusetts on Sunday, May 30, 1630. Moving west with the country, the Vincent’s had eventually established themselves in western Pennsylvania, in great degree through the efforts of the future Colonel’s maternal grandfather, Captain Martin Strong. An industrious pioneer, he had worked as territorial surveyor, and became a prosperous landowner.

Strong Vincent’s own father, Bethuel Boyd Vincent, son of a judge, likewise had many civic and political connections in Erie, and appreciated the value of a good education. Thus, when his son Strong Vincent (note the nod up the family tree,) was born in 1837, he would grow up well-read, in an educated environment. This stood him in good stead as he matured, pursuing a higher education at Hartford’s Trinity College from 1854 in the family’s “ancestral homeland” of Connecticut. It was there he met his future wife, one Elizabeth H. Carter. An insult to Elizabeth led Vincent to attack a man and saw his transfer to Harvard in 1856 where he graduated in 1859. He returned to Erie to read law.

Internet Archive

Note that episode in his life – “an insult to Elizabeth led Vincent to attack a man.” (!) In an instant, it reflected a certain code; a particular morality; a bit of his personal belief system.

War’s outbreak resolved another issue – In April of 1861, Vincent and Elizabeth were married! Yet the young man lay aside new bride, and a promising law practice, for the uncertainties of war. There, his leadership skills were on full display, first as Colonel John McLane’s second in command the 83rd PA, then as full Colonel following McLane’s death at Gaine’s Mill. His subsequent rise to brigade command verified the previous decisions. So it is right to enquire – where is such skill found?

Vincent’s background had prepared him, perhaps unwittingly, for the responsibilities he would assume. Educated in comfortable surroundings, with a mind honed for the law, he had also served an iron-moulder in his father’s foundry for two years, and a clerk there for two more. He knew of hard work.

It was typical, in the better colleges of Vincent’s day, to study lengthy poetry dealing with long-forgotten historical events, especially if there was an inspirational moral to be extracted out of it somewhere. Classic ancient battles of the Greeks and the Romans were fair subjects.

One of these episodes took place around 509 B. C., during the war between Rome and the invading Etruscans. Only by stopping the hostile army at the Tiber River would Rome be safe. In 1842 a distinguished Englishman, Thomas Babington Macaulay, an alumnus of Hartford’s namesake Trinity College in Britain, produced Horatius at the Bridge, a seventy-verse long tome which dealt with a hero of that battle.

As Horatius opened, describing the chaos, the picture it painted was clear and unambiguous; even if the language is perchance a bit dated: (v. VIII)

But by the yellow Tiber

Was tumult and affright:

From all the spacious champaign*

To Rome men took their flight.

A mile around the city,

The throng stopped up the ways;

A fearful sight it was to see

Through two long nights and days.

[*champaign – level, open country; plain].

But Vincent, now a hardened combat soldier, no longer had the luxury to actively reflect upon his school-days. Other things were foremost on his mind. He had a serious task ahead. He had a solid vision of home, and what he was fighting to defend. He assured Elizabeth, following her departure from winter quarters – “If I fall, remember you have given your husband to the most righteous cause that ever widowed a woman.”However, lessons acquired in school are not so easily disposed of. Sometimes, they burrow deep, and reappear at odd moments in slightly different formats. So it was on 1 July, 1863, when after a long fatiguing march, approaching Hanover, the brigade went into bivouac. Almost immediately came news of the battle at Gettysburg, with orders to continue the advance. Just before reaching Hanover, it is recorded that Col. Vincent sent back for the colors and the band of the 83rd PA Regiment.

Let us jump back for a moment to Horatius, that poem Vincent heard in school, for a brief moment. At a critical juncture, a decision is made to save Rome from the “fourscore thousand” who would assail it, by cutting down the bridge to preserve the city. However, that can’t be done fast enough; someone must confront the Etruscans at the gate. In Horatius, (v. XXVII,) one finds the following stirring words:

Then out spake brave Horatius,

The Captain of the Gate:

"To every man upon this earth

Death cometh soon or late.

And how can man die better

Than facing fearful odds,

For the ashes of his fathers,

And the temples of his gods.

Now, with the issue still uncertain, and a victorious foe of unknown size sure to be confronted soon, Col. Vincent reverently bared his head as the unfurled colors caught the breeze. Flush with emotion, he glanced over to Captain Clark, his adjutant, and rhetorically queried him in a thoroughly American comprehension of Macaulay’s words, “What death more glorious can any man desire than to die on the soil of old Pennsylvania, fighting for that flag?”

The following day, 2 July 1863, on the slopes of Little Round Top, Col. Strong Vincent fully demonstrated his comparability to any classical hero of antiquity. Sensing the right flank of his brigade beginning to waver, he approached the scene and leapt upon a large rock, promiscuously displaying a riding crop. “Don’t give an inch!” he firmly instructed his men. Shortly thereafter, he was mortally wounded. In something of an understatement, he was observed to comment, “This is the fourth or fifth time they have shot at me, and they have hit me at last.”

Remarked upon in his times by many for his critical role in helping to preserve the Union left, General Meade recommended him for promotion to Brigadier General that evening. Vincent, like Horatius in times before him, has had his likeness sculpted. Yet, outside the arcane circle of those who share our interest, his example is infrequently remembered. If we no longer script heroic ballads, as once was done for Horatius, can we count on raising up the next crop of Strong Vincents when we need them?