Last updated: October 30, 2020

Article

Mary Clemmer Ames and “Ten Years in Washington”

Frontspiece of the book Ten Years in Washington

March being “Women’s History Month,” it seems appropriate to say a little something about a woman whose name is more than likely unknown to most present-day Americans. She wasn’t a leader in the abolitionist movement or a suffragist. She gained no fame as an advocate of temperance. She was, though, a lifelong resident of the District of Columbia, and chronicled the Washington scene from the 1860s into the early 1880s.

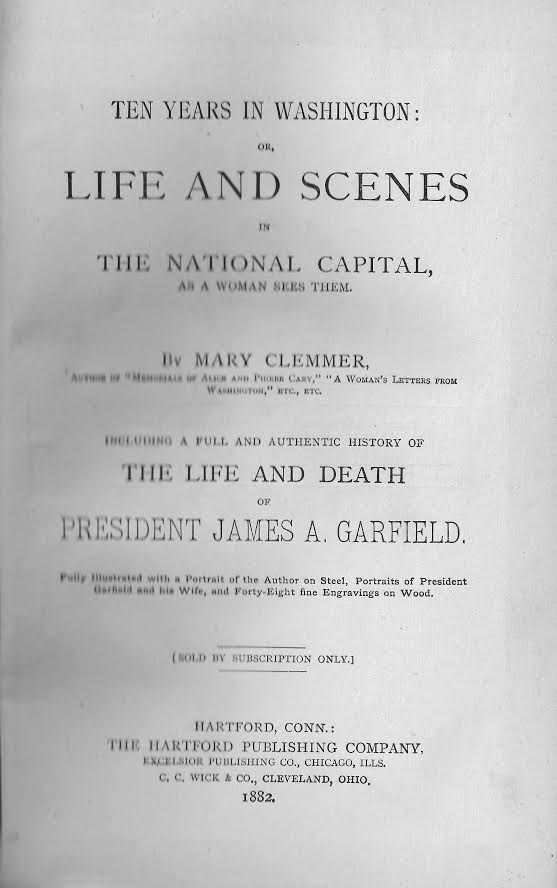

Her name was Mary Clemmer Ames (1839-1884) and her book Ten Years in Washington, first published in 1874, is an engaging account of the notable buildings and agencies centered in the nation’s capital, and the people whose activities breathed life into them. Her descriptions of the many individuals, male and female, prominent and not, who set the social standards of the political class, or who did the everyday work of the federal bureaucracy, are intelligent, sympathetic, at times witty, and fully human portrayals.

Wikipedia

This post will pay most attention to the commentary of Mrs. Clemmer that particularly illustrated the role of women of “Gilded Age” Washington. However, as James A. Garfield is inevitably the subject in some way of what you read on this page, what Mary Clemmer had to say about him will not be neglected.

Ten Years in Washington covers a wide variety of topics. There is a historical treatment of the designation of ten square miles of land given by the states of Maryland and Virginia for the establishment of the District. Mrs. Clemmer goes into great descriptive detail about the Capitol building, “the President’s House,” the Library of Congress and the Smithsonian. The inner workings of the U.S. Treasury, the Post Office and the Patent Office and other agencies are a prime focus of her writing. The State Department, the Army, the Navy, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the Interior Department all came into view.

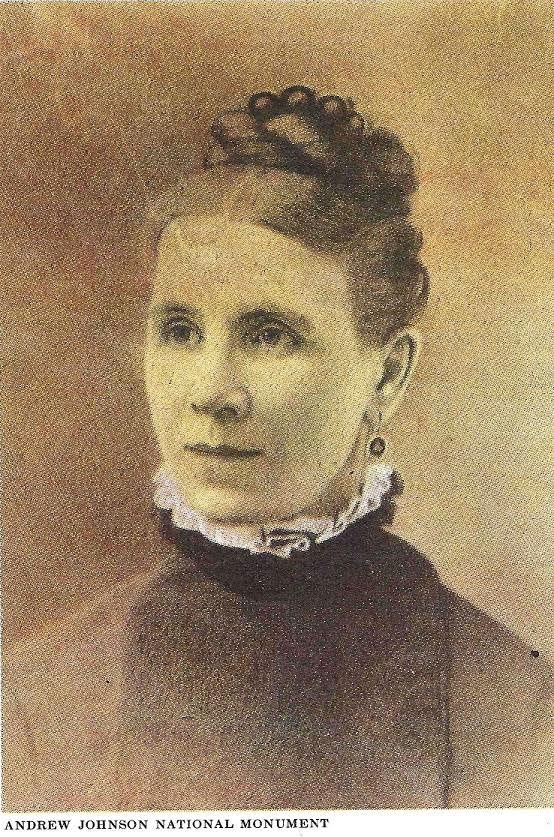

Mrs. Ames had something to say about every mistress of the White House, whether she was the President’s wife or daughter (there is a highly complimentary portrayal of Martha Patterson, daughter of Andrew Johnson). Her portrayal of Sarah Polk includes the following:

Mrs. Polk, intellectually, was one of the most marked

women who ever presided in the White House. A lady of

the old school… her attainments were more than ordinary…

Never a politician, in a day when politics… were forbidden

grounds to women, she no less was thoroughly conversant

with all public affairs…

She was her husband’s private secretary, and, probably,

was the only lady of the White House who ever filled that

office. She took charge of his papers, he trusting entirely to

her memory and method for their safe keeping… [and when

needed] it was Sarah’s ever ready hand that laid it before his

eyes.

Wikipedia

Mrs. Grant’s morning receptions are very popular, and

deservedly so. This is not because the lady is in any sense

a good conversationalist, or has a fine tact in receiving, but

rather, I think, because she is thoroughly good-natured, and

for the time, at least, makes other people feel the same. At

any rate, there was never so little formality or so much

genuine sociability in the day-receptions at the White House

as at the present time.

Andrew Johnson National Monument, National Park Service.

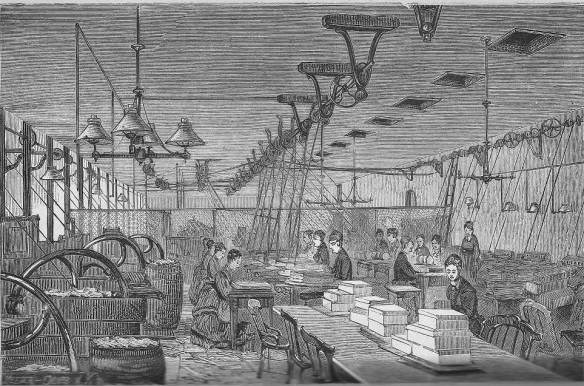

Ten Years in Washington is full of interesting facts and anecdotes. Many of these illustrate the contributions and the plight of female federal workers. Here, in her chapters on the Treasury Department, Mrs. Ames lauds the ability of the women who performed their work so well:

“After the great Chicago fire in 1871, cases of money to the value of one hundred and sixty-four thousand, nine-hundred and ninety-seven dollars and ninety-eight cents, were sent to the United States Treasury for identification… All these charred treasures were placed in the hands of a committee of six ladies… What patience, practice, skill, were indispensable to the fulfillment of this task, it is not difficult to conjecture… After unpacking the money… the ladies separated each small piece with thin knives made for the purpose, then laying the blackened fragments on sheets of blotting paper, they decided by close scrutiny, the value, genuineness, and nature of the note. Magnifying glasses were provided, but seldom used…’”

Mrs. Ames identified the members of this committee of six as Mrs. M. J. Patterson, Miss Pearl, Mrs. Davis, Miss Shriner, Miss Wright, and Miss Powers. “The most noted case [Mrs. Patterson] ever worked on was that of the paymaster’s trunk,” that sank with the Robert Carter, in the Mississippi River.

“After lying three years in the bottom of the river, the steamer was raised, and the money, soaked, rotten and obliterated, given to Mrs. Patterson for identification. She saved one hundred and eighty-five thousand out of two hundred thousand dollars, and the express company, which was responsible for the original amount, presented her with five hundred dollars, as a recognition of her services.”

And yet, the familiar refrain best summed up in the old adage, “The more things change, the more they remain the same,” was as pertinent in the distant 1870s as it it today.

Of the forty-five ladies in the Internal Revenue Bureau,

there is but one, and she is fifty years of age, who has not

more than herself to support on the pittance which she is

paid. Nevertheless, whenever a spasmodic cry of

‘retrenchment’ is raised, three women are always dismissed

from office, to one man, although the men greatly out-

number the women, to say nothing of their being so much

more expensive.

Today’s crusaders for “equal rights for equal pay” have soul mates going back 140 years and more. There are connections between we, the living, and past generations of Americans. History is not bunk. The past is not entirely past. It is not dead.

For many years Mary Clemmer authored a column called, “A Woman’s Letter from Washington.” This journalistic exploit for the New York Independent encouraged her passion for description, and her interest in the common man and woman. Her delight in limning the social elite sprang from that same reportorial flare.

Ten Years in Washington

It then comes as no surprise that in the March 27, 1879 issue of that column she presented a word portrait of Congressman James Garfield that mixed reservation with admiration:

“In mental capacity, in fine, wide, intellectual culture, no Republican for the last decade has equaled, much less surpassed him… Were it possible to honor his moral purity as one must his intellectual acumen, he would be as grand in personal and political strength, that no whim of man, no passion of the hour, no mutation of party could depress, much less overthrow.”

A month later, Garfield learned of the column’s complex account of his character through a letter from a Boston, Massachusetts correspondent, Jeremiah Chaplin. According to Garfield’s diary entry for April 27, 1879, Chaplin quoted the column, which “criticizes me in a vague, unjust, and indefinite way.” Calling on Mrs. Ames a few days later, he left [Chaplin’s] letter “for her to read at leisure and to let me know what she meant by her language. She asked me to call on Wednesday evening to see her about it. I am curious to know what she will say.”

Two days later, Garfield called on Mrs. Clemmer at seven o’clock in the evening. “I had a strong conversation with her on the subject,” he wrote afterward. Did she remind him of the marital infidelities of which he had been accused some years earlier? Did he refute these as unjust? Did he invoke the current state of his relationship with his wife as his defense? Alas, the content of that conversation is not known.

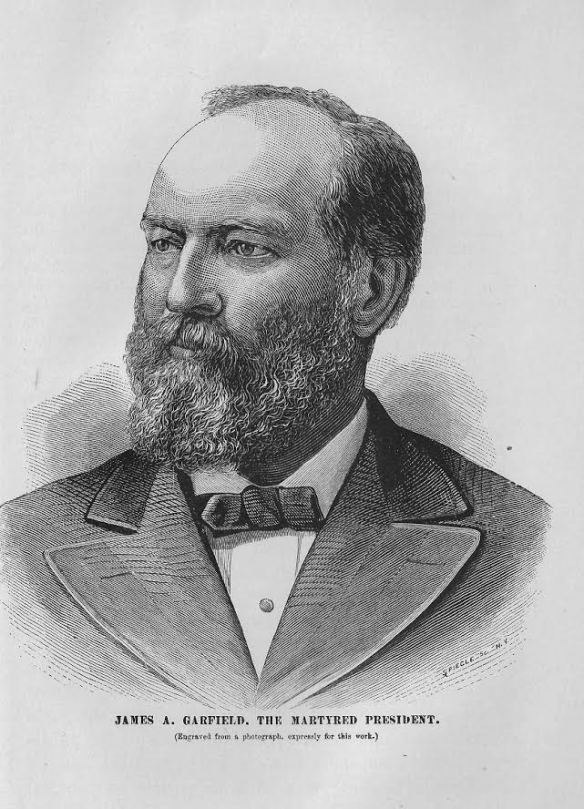

What is known is that in 1882, the year after President Garfield’s assassination, a new edition of Ten Years in Washington appeared. It now featured, “A Full and Authentic History of the Life and Death of President James A. Garfield.”

Ten Years in Washington, Hartford Publishing Co., 1882

Was the inclusion of the Garfield biography intended as a well-deserved homage to the late president whose character the author had once questioned, or, (more cynically) was it designed to boost new sales of the original book?

The biography includes passages on First Lady Lucretia Garfield, who, returning from her own convalescence at Long Branch, New Jersey

bravely took her place by her husband’s side, and

comforted and cheered him during his long and weary

fight for life. How grandly she rose to the occasion,

how tenderly she endured the weary weeks, always

wearing a cheerful face, while her heart was breaking

with its cruel load, the whole world knows. Her heroic

devotion to her husband grandly typified the loyal and

self-sacrificing spirit of wifehood, which finds no more

conspicuous illustration than in our American homes…

Library of Congress

Cognizant of all that had occurred between 1879 and 1882, driven perhaps by the changed perspective that death brings, Mrs. Ames concluded in 1882 that, “President Garfield was large-framed, large-brained, and large-hearted.”

He was six feet tall in height and was a splendid picture

of a man. His personal character and habits were clean and

pure, and his home life at Mentor or Washington as

simply delightful. … In a word, James A. Garfield was a

man physically, intellectually, and morally who was an

honor to his country and … no more imperishable name

will ever adorn our country’s annals.

It was not long after this writing that Mary Clemmer herself died at the age of 45, only a year after her 1883 marriage to Edmund Hudson, editor of the Army and Navy Register. Her earlier marriage to Daniel Ames ended in divorce in 1874, the same year in which Ten Years in Washington was first published.

Death came early to Mary Clemmer Ames Hudson, but she has left behind a wonderful chronicle of Gilded Age Washington.

Written by Alan Gephardt, Park Ranger, James A. Garfield National Historic Site, March 2017 for the Garfield Observer.