Part of a series of articles titled The Midden – Great Basin National Park: Vol. 25, No. 1, Summer 2025.

Article

Mapping Vegetative Change

This article was originally published in The Midden – Great Basin National Park: Vol. 25, No. 1, Summer 2025.

NPS/M. Horner

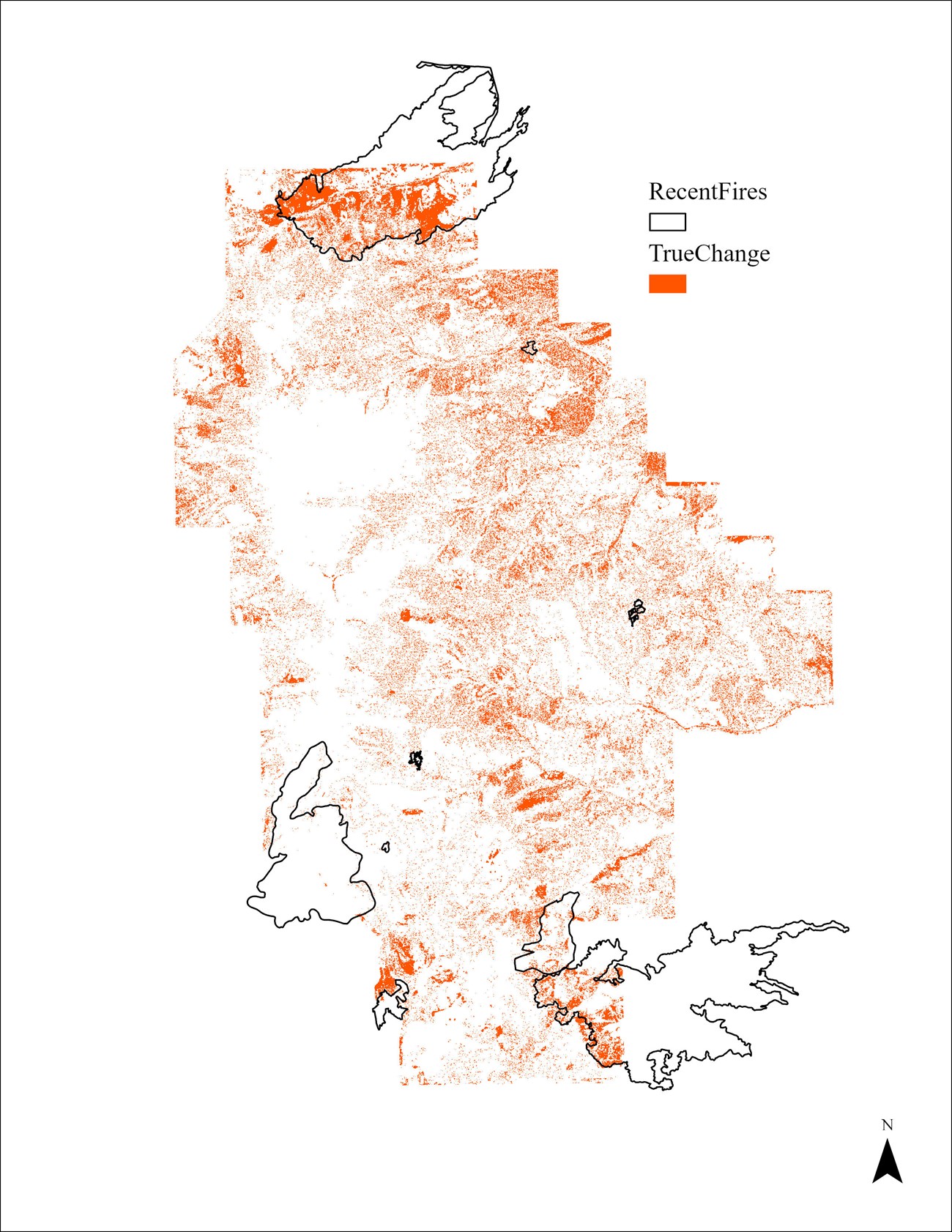

Look up at the South Snake Range from Snake Valley and changes in the vegetation growing on the mountain side may not be obvious, especially if your view of Doso Doyabi or Wheeler Peak is new or brief (Figure 1). But changes are happening. Some are subtle like the change in needle color of conifers stressed or killed by insects. Some are more dramatic like the immediate change that comes after a wildfire. Other changes are harder to see because of their scale or location. We can visualize all these changes with the help of satellite imagery, remote sensing, and mapping vegetation at a broad scale.

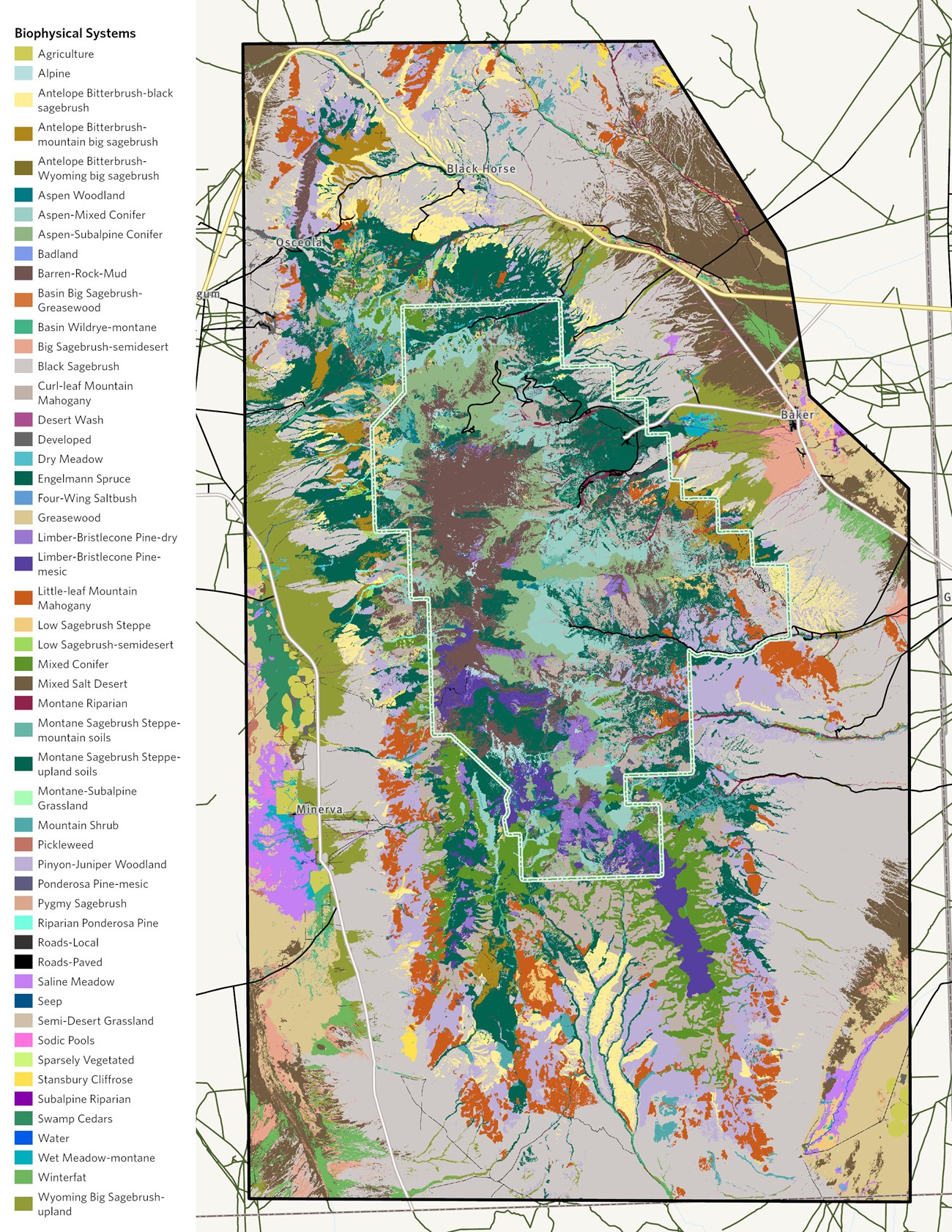

To map vegetation and measure change, the park partnered with The Nature Conservancy (TNC). This partnership started almost 20 years ago when TNC produced the first vegetation map for Great Basin National Park. We partnered with them again in 2022 to expand the study area to lands outside the park and look at changes in park vegetation since the first mapping effort (Figure 2).

The Nature Conservancy

NPS/M. Horner

NPS/M. Horner

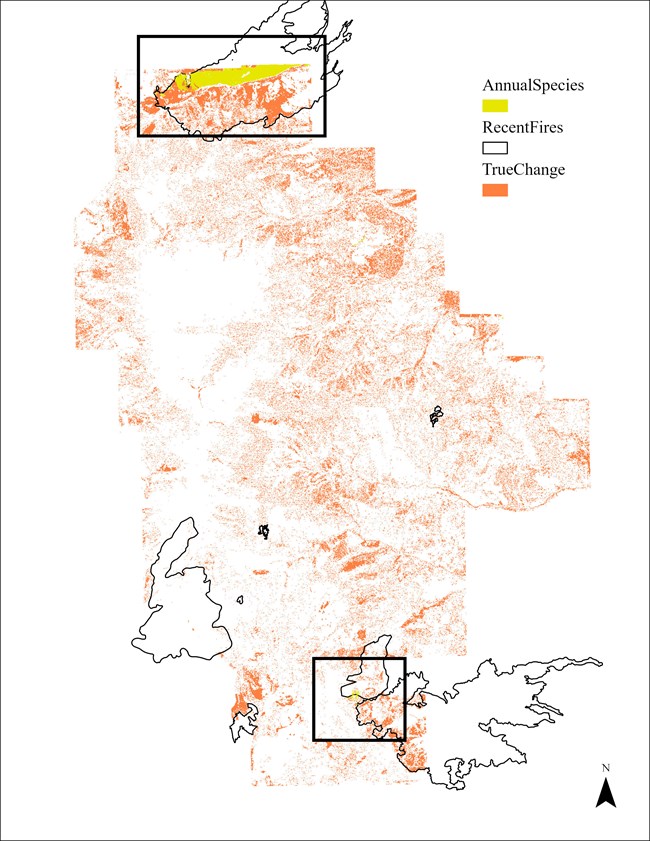

For the Strawberry Fire, some of the most noticeable change was an increase in annual species – cheatgrass in this case (Figure 4). Mapping highlighted other issues harder to see from the ground like the loss of aspen, a fire adapted species (Figure 5). The park has lost aspen clones in some areas because of fire exclusion – giving even more urgency to reintroduce fire to the landscape to prevent further loss of ecologically and aesthetically important vegetation.

NPS/M. Horner

Comparing the same landscape at two different time periods reveals management challenges. But it also highlights opportunities for restoration, fuels reduction and prescribed fire projects, and helps the park prioritize where to work. As with all modeling and remote sensing exercises, it can only get us so far. Making informed decisions requires getting out into the field to properly plan and implement successful management and restoration.

This project was funded by the Bureau of Land Management SNPLMA (Southern Nevada Public Land Management Act) Program.

Last updated: May 21, 2025