Last updated: July 17, 2024

Article

The Orchards at Manzanar: Continuity, Care, and Community

Manzanar is a location that is partly defined through its boundaries, transformations, and distances. There are also threads of continuity woven throughout the landscape. One such thread is the orchards at Manzanar National Historic Site. Despite cycles of use and abandonment, the orchards at Manzanar National Historic Site have remained a constant connection to the site's landscape and history.

NPS, 2022

The Orchards

Manzanar National Historic Site is located in the Owens Valley of eastern California, an arid region bounded on the west by the Sierra Nevada Mountains and the east by the White-Inyo Mountains. The area’s horticultural history begins with the Owens Valley Paiute, who constructed irrigation ditch systems and diversion dams to bring water to plants. Early homesteaders planted fruit trees and continued to irrigate former Paiute fields by diverting water from the streams that flowed from the Sierra Nevada.

Owens Valley Improvement Company: Production for Profit

When the Owens Valley Improvement Company (OVIC) secured water rights to establish an agricultural community in 1910, it named the new development after the Spanish term for apple orchard: Manzanar. The community grew several apple varieties and other fruits, and the area was quickly recognized and marketed for its favorable fruit production conditions. As the orchards grew, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP) began to acquire land in the valley, in the interest of protecting the watershed for the Los Angeles Aqueduct and securing water rights in the area. As a result, many residents of the town of Manzanar relocated by 1934, and the LADWP removed many trees and homes. However, about one thousand fruit trees remained.

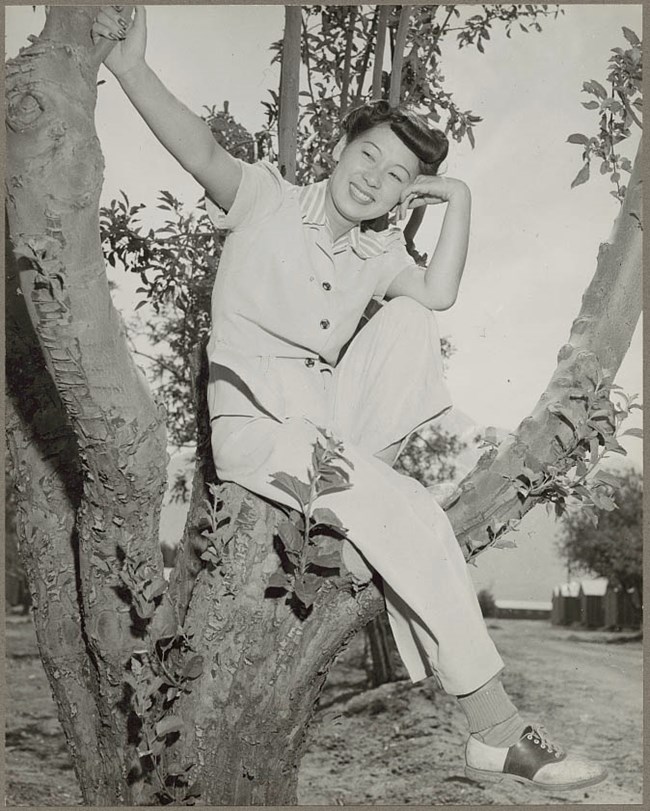

Shiro and Mary Nomura Collection, Eastern California Museum

Manzanar War Relocation Center: Production for Perseverance

The orchards and fruit trees at Manzanar were largely abandoned until 1942, when the War Relocation Authority (WRA) established the Manzanar War Relocation Center in response to Executive Order 9066, which allowed the military to forcibly relocate Japanese and Japanese American people on the Pacific Coast of the United States to incarceration centers.

WRA criteria for identifying locations for the centers focused on three factors: accessibility to railroad lines, isolation from military installations, and agricultural potential. The abandoned orchards at Manzanar were recognized as potential agricultural assets for making the incarceration center self-sufficient. The WRA laid out the center upon the former town of Manzanar, layered on land ownership parcels, roads, and existing orchards. Fruit trees that coincided with barracks blocks were retained as street trees or part of small gardens. Others growing in orchards were retained within the camp. When incarcerees first arrived in 1942, about 600 apple and 400 pear trees remained, supported by existing irrigation ditches.

Thanks to the care of several skilled Japanese American horticulturalists and orchard crews, comprised of incarcerated individuals, the fruit trees were reinvigorated and began to produce an abundance of fruit. The crews harvested apples, pears, and other fruits to supply food for people held at the center.

When World War II ended in 1945, the federal government abandoned the Manzanar War Relocation Center and the land remained undeveloped for five decades. Remarkably, some fruit trees persisted.

National Park Service: Production for Preservation

In 1997, the property was acquired by the National Park Service. The remaining fruit trees were recorded in a Cultural Landscape Inventory (CLI) in 2004 and a Cultural Landscape Report (CLR) in 2006. Only the hardiest fruit trees had survived without care in the harsh, high desert environment. The predominant survivors were pear trees, a tap-rooted tree.

Following immediate stabilization, longer term planning and maintenance efforts have resulted in grafting and replanting projects.

Today, 144 trees remain that are associated with the various historic periods of the landscape: early agricultural development in the valley, the Manzanar Town era, and the War Relocation Camp period. Some of these surviving trees are about 105 years old. They have lived as witnesses through the various periods of use and neglect and endured decades in hot sun and harsh winter, cared for by different hands with their fruit shared among many.

Francis Stewart, photographer. US War Relocation Authority, D-552. Library of Congress.

The People

Today, David Goto is primarily responsible for care of the orchards. A Gardener at Manzanar National Historic Site, Goto’s extensive knowledge of the orchard history and care spans the particulars of horticulture, environmental conditions, and local connections that are essential for its success.

When the War Relocation Center was established, the new residents of Manzanar included a handful of experienced Japanese American orchardists. Upon their arrival, an orchard crew was created under the supervision of Wartime Civilian Control Administration (WCCC) staff member Frank Cummings and incarceree orchard supervisor Ted Akahoski. The WCCC was established by the Army in 1942 to carry out the military evacuation program. Akahoshi was a 1913 graduate of Stanford University and manager of the Produce Merchants Association in Los Angeles. As a supervisor of the orchard program, Akahoski's position was one of highest-level jobs available to Japanese American incarcerees. Takeo Shima was the crew foreman, assisted by Hideo Marumoto and Gummi Watanabe with a crew of approximately 40 people. Shima was a nurseryman who had years of experience at a large commercial orchard in Bakersfield. Initially, the crew focused on pruning to rejuvenate the fruit trees. As the health of the trees improved, the crew maintained the orchards and managed the harvest and distribution of the crop.

The orchard crew also contended with pests, which sometimes included children. In one example, an eight-year-old boy was unable to resist the allure of a pear and picked it from the tree, still unripe. As punishment, the crew made the boy drink cod liver oil. That boy grew up to be an experienced gardener, and he shared this memory with park staff. Goto sent him scion wood cuttings from Bartlett and Comice pear trees at Manzanar, along with a small bottle of cod liver oil. The gift was received with good humor.

The landscape is a stark reminder of the injustice of Japanese Americans taken from homes and lives to be incarcerated at Manzanar between 1942 and 1945. It is also an opportunity to connect to the people who share an enduring relationship to the fruit trees of Manzanar. People incarcerated at the War Relocation Center carry memories of the orchards that they pass on to their descendants. Residents in the Owens Valley also recall picking the fruit during the period of neglect before the NPS took ownership. Goto mentioned a particular excitement spreads at bloom time and harvest time, when the abundance of the trees is most evident. The fruit is harvested and distributed to the community each year, spreading goodwill and sustaining relationships.

NPS

Today, the maintenance staff is small and committed, sharing skills that will help ensure continuing care. Goto noted that as the park transitions from orchard rehabilitation to maintenance, more people may have a chance to participate in caring for the orchards. While shaping young trees requires more specialized skills to ensure the health and longevity of the trees, maintenance tasks like deadwood removal can expand opportunities for community involvement and training.

Regional Cultural Resource Award

Recognizing David Goto's WorkPreservation Maintenance

Techniques and Challenges

Some efforts to preserve the orchard trees reflect historic practices and concerns, while others have evolved as the trees mature.

Managing water in the arid valley had been a priority for all who have lived here. Prior to European American settlement of the area, Owens Valley Paiute resided in year-round villages and constructed irrigation ditch systems. Later, the Owens Valley Improvement Company developed irrigation to support orchards and town residents. Incarcerated laborers at Manzanar War Relocation Center maintained an extensive irritation system of both reconditioned and new, hand dug irrigation ditches to support orchards and agriculture.

Irrigation is essential for establishing young trees and protecting the health and longevity of old trees. Drought stress can also make trees more susceptible to other pest infections. Today, the irrigation system is supplied by a historic well, a solar-powered pump, and driplines. Maintenance of the system takes into account the impacts of animals and incorporates water conservation practices like cover crops and mulching.

Decades of abandonment favored the reestablishment of natural processes, including the return of wildlife like Tule elk, deer, bear, and ground squirrels. Animals can damage trees by rubbing, clawing, breaking branches, browsing, and burrowing. Today, the park uses fencing to reduce the impacts of wildlife on the fruit trees. The trees are particularly enticing to wildlife during the fruit ripening period.

Fire blight is a native bacterium that attacks pears and other fruit trees through their blossoms. Goto protects the trees with organic lime sulfur and copper sprays during blossoming, and by pruning out any infected tissue for weeks afterwards. Dead or diseased wood in fruit trees provide entry points for pests and many diseases that can cause damage to other parts of the plant, such as shoots, limbs, and roots. Goto removes deadwood in the tree canopies to promote tree health and longevity.

Propagation creates a new or replacement tree for planting in an orchard, using cuttings from existing historic trees as genetic source material. Grafting is used in the propagation process to join two trees together. The scion carries the genetic material of the fruit variety to form the trunk and canopy, and the graft union connects the scion to the rootstock to form the root system.

At Manzanar, historic germplasm is conserved by collecting scions for grafting from historic trees in the park or locally. Goto is preparing to replant the North Wilder Orchard in 2023 with a selection of apple varieties grown by the early 20th century town of Manzanar. With irrigation and fencing already in place, five apple varieties will be planted: Jonathan, Winesap, Newtown Pippen, Arkansas Black, and Yellow Bellflower. In this case, old trees from the local town of Independence in the Owens Valley provided genetic material to match historic varieties known to have been grown at Manzanar.

Several National Park Service publications assess and document existing conditions of the cultural landscape, guiding immediate field stabilization and maintenance efforts as well as long-term preservation strategies. A Landscape Stabilization Plan was produced in 2005. The Cultural Landscape Cultural Landscape Report (CLR) was published in 2006, followed by the Orchard Management Plan (OMP) in 2010. These documents describe the history, features, and care of the orchards over time, serving as a valuable tool for Goto and others as they make decisions about the orchards and the landscape.

One factor that is both essential and challenging to success in an orchard program is time. Goto noted that the outcomes of orchard management practices can take many years to realize, so patience and persistence are necessary.

The orchards at Manzanar tell a story of continuity, persisting across periods of use and neglect. Through many decades and for different reasons, people have cared for these trees, and the orchard history and tree care are woven through the landscape history. These remarkable trees continue to provide food and cultural sustenance, both to residents of the Owens Valley and to the formerly incarcerated people, along with their descendants.

NPS, 2022