Part of a series of articles titled Eisenhower in World War II.

Article

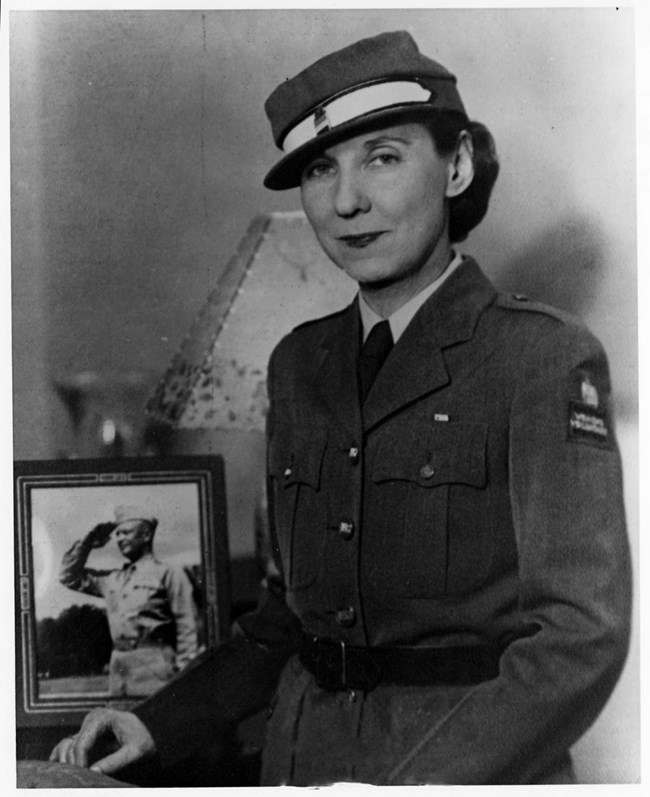

"Spine of Steel": Mamie Eisenhower in World War II

Eisenhower Presidential Library

During World War II, Dwight “Ike” Eisenhower would achieve some of the greatest accomplishments of his military career, though he didn’t do it alone. He relied on the support of his wife of twenty-five years, Mamie. While Ike took up military positions overseas, Mamie remained in the United States. She volunteered, answered correspondence, managed publicity storms, and took care of her friends and family while grappling with mental and physical challenges. As her husband’s role and responsibilities grew, so too did Mamie’s. Though she was the wife of the Supreme Commander, she also had some typical wartime spouse experiences.

First, Mamie had to contend with a problem common to Army wives: housing. After packing up and moving abruptly to D.C. from Fort Sam Houston, Mamie and Ike only spent a short period in D.C., then moved to Quarters #7 in Fort Myer, Virginia in April 1942. After about two months in Quarters #7, Mamie was given one week to move again. Thankfully, Harry Butcher (later Ike’s naval aide) offered for Mamie to share an apartment with his wife Ruth and their daughter at the Wardman Tower in D.C. With housing finally sorted out, Mamie moved on to service.

Though Mamie wasn’t in the military, she did her part to support the war effort. She frequently volunteered with the Red Cross and served as a waitress at the canteen for Soldiers, Sailors and Marines. She also volunteered with the Army Relief Society, United Service Organization, and American Women’s Volunteer Service. While volunteering, Mamie tried to conceal her identity as the wife of the Supreme Allied Commander.

Beyond volunteering, one of Mamie’s major goals was to maintain the couple’s privacy throughout the war and defend Ike from people hoping to exploit his position as Supreme Commander. Many people wrote letters to Ike requesting that he move their brother, son, husband, or other loved one away from the front lines. Ike also received his fair share of people seeking favors, such as a wartime promotion. Mamie fielded many of these requests and personally responded to every one of the thousands of letters she received. She also navigated media publicity as her husband rose through the ranks. During the war, Mamie said that reporters took up two to three hours of every day. Ike wrote in a letter to Mamie on March 2, 1943 that “all through this publicity storm you’ve been tops – sensible, considerate, and modest.” Mamie kept reporters away from the couple’s personal business, and she never accepted gifts from those hoping to benefit from her or her husband’s position. From jewelry to hats to roses, reporters tried to bribe Mamie into giving them a scoop. She never accepted these gifts, nor did she allow herself to be coerced into an interview.

Eisenhower Presidential Library

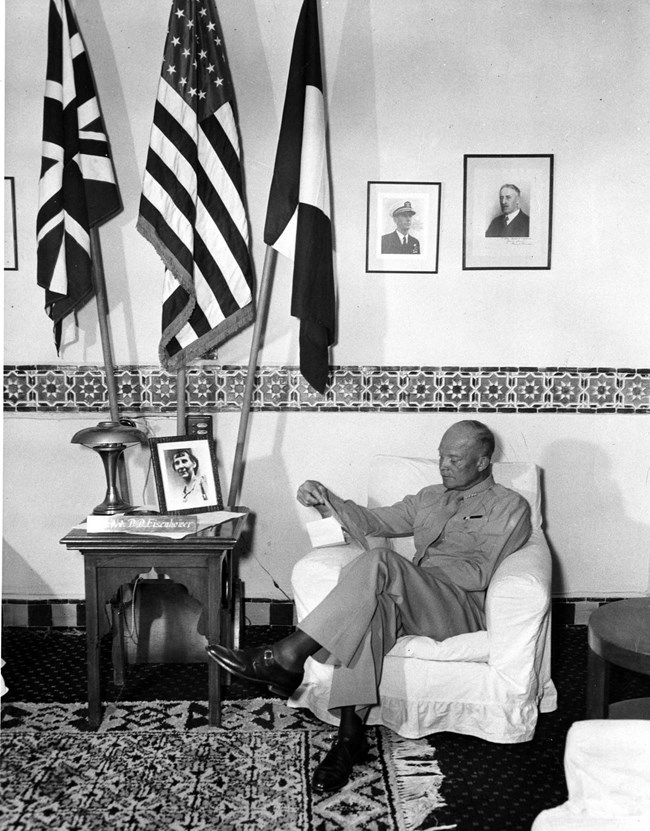

Mamie’s jaded response to attempts to exploit her position also reveals how lonely she was. Mamie and Ike missed each other desperately. Ike wrote Mamie 319 letters over the course of the war, often asking her not to forget him. The pair only saw each other twice during the war, and Ike was the only one of the WWII five-star generals to spend the war years without his wife. In December of 1943, Ike wrote to Mamie about his concept of an ideal post-war experience, saying, “I always picture a little place far away from cities (but with someone near enough for occasional bridge) and the two of us just getting brown in the sun, (and possibly thick in the middle).” Though the couple would eventually do just that at their Gettysburg farm, they wouldn’t purchase their home for another seven years.

Since Ike and the couple’s son John were both away, Mamie’s social circle shrank to her extended family and a handful of Army wives. While the wives could be a source of support, they sometimes added to Mamie’s stress. Army wives often assigned themselves to the ranks of their husbands. For instance, generals’ wives saw themselves as higher in rank than captains’ wives, and the resulting cattiness added to Mamie’s social concerns. Even when Army wives were supportive, Mamie often couldn’t spend time with them. Though she had enjoyed going out with her friends in the interwar years, Mamie refused to go out at all during the war. She stuck to the decision despite pressure from her friends, stating adamantly that she would not be seen partying and drinking while Ike sent American soldiers to war.

Eisenhower Presidential Library

Beyond loneliness, Mamie also had to navigate the nastiness of Washington, D.C. gossip. One widespread rumor claimed Mamie was secretly an alcoholic. Because of the lack of balance caused by her physical illnesses, Mamie often stumbled in public. The rumor mill took this as evidence that Mamie was drunk. Of course, accusations of alcoholism weren’t the only rumors Mamie had to contend with. In 1976, John published Ike’s wartime letters in a book called Letters to Mamie. By publishing the letters, John hoped to fend off rumors that Ike was engaged in a wartime romance with his driver, Kay Summersby. These rumors followed Ike and Mamie throughout WWII and beyond. During the war, Mamie wrote Ike occasional letters bringing up Kay, mentioning incidents like Kay following Ike to Algiers after serving as his driver in London. However, Ike refuted these rumors time and time again. He wrote to Mamie in 1943 that “if anyone is banal and foolish enough to lift an eyebrow at an old duffer such as I am in connection with Waacs [sic] --Red Cross workers – nurses and drivers – you will know that I’ve no emotional involvements and will have none.” In an interview late in her life, Mamie said that she never really worried that there was anyone else in Ike’s life during the times the couple spent apart. Though Ike and Kay were very close during the war, there is no existing historical evidence that the pair engaged in a physical affair. Many of those closest to him during the war spoke out against the claim after Past Forgetting, Summersby’s ghostwritten memoir, was published.

Mamie was under physical as well as emotional strain. Mamie had a heart condition caused by a childhood case of rheumatic fever that often confined her to her bed. She also suffered from stress, as well as several food allergies, headaches, and insomnia. Most significantly, Mamie suffered from Meniere’s syndrome, a severe inner-ear disorder that caused “lack of equilibrium.” Mamie recalled some attacks that made her so dizzy that she couldn’t walk, resorting to crawling to the kitchen in the morning. Mamie’s doctors told her they couldn’t perform surgery on her ear to correct the issue. In an interview late in her life, Mamie said that because of the syndrome, “I’m black and blue from walking around my own house.” She often bumped into furniture or fell because of her vertigo and inability to balance.

On top of everything she went through as the General’s wife, Mamie also had to contend with the everyday stresses of the war. Food rationing further curtailed Mamie’s social life and connections to others. In the early days of the war, Mamie recalled that she and her friends “never got a decent meal unless we all got together and everybody put her things in.” Like many American women, Mamie worried about her husband and what he was doing in the war. Even as the wife of the Supreme Commander, she never knew more than what she read in the newspaper about Ike’s position and activities.

Despite the problems Mamie faced in wartime, she always rose to the occasion with her trademark wit and charm. In an interview late in her life with Barbara Walters, Mamie said, “I never worry about myself at all. I knew I could stand up to anything.” By weathering two world wars and the Great Depression without her bangs falling out of place, Mamie lived up to her reputation as a woman with “a spine of steel,” as the chief usher of the White House, J.B. West, called her.

Last updated: September 1, 2023