Last updated: August 29, 2024

Article

Making Way for an Army: Archeology at Muhlenberg’s and Weedon’s Brigades

Archeological projects over the last 50 years have sought to reconcile historic accounts with reality. By considering each hut both individually and in relation to one another, archeology at Valley Forge personalizes the starkness of the soldiers’ six-month stay and details the ingenuity with which they tailored their surroundings to their needs.

The Disorder of Orderly Living

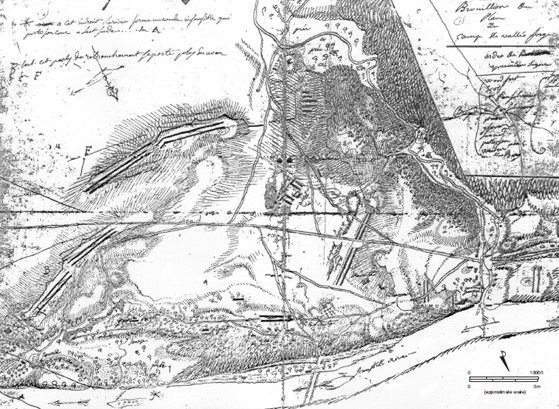

In 1972, in advance of the construction of a parking lot, the William Penn Memorial Museum initiated archeological excavations on the site allocated to Muhlenberg’s and Weedon’s Brigades in Duportail’s plan. A resistivity survey in the area west of the parking lot and excavations to test the results of this survey took place in 1973. With the help of students from lower Merion High school and the University of Pennsylvania, archeologists identified a total of 18 Revolutionary War-era huts, of which 14 were completely excavated.Within the hand-excavated ten-foot square trenches, rectangular stains of the huts were usually visible beneath layers of turf, top-soil, and underlying soil. At this level, a fireplace in a hut could be seen as an area of burnt earth protruding from the hut’s outline. On paper, General Orders aimed to standardize the dimensions and layouts of the huts, but archeology shows that in practice, hut sizes varied considerably.

The easternmost hut measures nine by ten feet plus a hearth extension. The softness of the floor toward the structure’s western wall may indicate the presence of bunks, which would have been practical if each hut hosted up to 12 men. Large and small postholes throughout would have reinforced the door, ceiling, and other furniture items. The hearth in this hut is set into a separate alcove, with some huts featuring distinctive corner fireplaces and one hut with no evidence of a fireplace at all.

Soldiers were not always engaged in military tasks. Archeologists recovered two pieces of iron barrel hoop reused as grills or broilers, which indicates kitchen and cooking activities. The team also found a small amount of extremely fragmentary animal remains in the huts. Their condition is explained as the result of at least two processes: the splitting of bones into small segments for wide-spread distribution and the extraction of marrow, and the deposition of waste inside the huts themselves. Cattle bones predominated, followed by sheep and then pigs.

Soldiers did have to exercise creativity in other ways, such as using a lead pencil possibly fashioned from a musket ball. Medical treatment also posed a concern. One small redware drug pot contained sulfur, which may have been used medicinally to alleviate the aftereffects of the smallpox vaccination or other skin disorders. Wine and case bottle sherds convey alcohol consumption. The scarcity of personal objects is typical of military sites where troops possessed arms and clothing and little else.

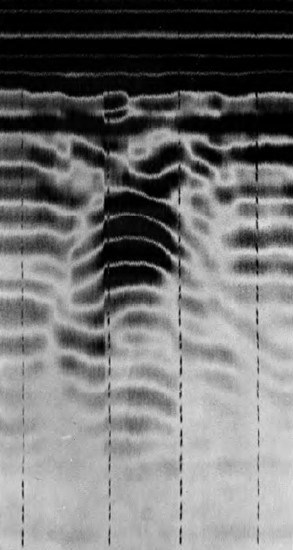

Subsequent archeological projects point to the potential resources yet to be documented. Between 1977 and 1979, the University of Pennsylvania’s Museum Applied Science Center for Archaeology (MASCA) used a magnetometer to pinpoint two offal pits and locate the magnetic disturbances of some of the hearths built into the soldiers’ huts. Aerial photography detected a new rectangular feature with an area of burning at one end, like the recorded Revolutionary War huts. Another aerial trace coincided with a track or road shown on Duportail’s map. Ground-penetrating radar (GPR) survey also revealed a rectangular stone structure. The feature has no known counterpart at Valley Forge, but sherds of a grey stoneware jug among the rubble may date to the encampment period.

Taking Ambiguities in Stride

The Revolutionary War-era huts in the Muhlenberg’s Brigade area are but a small sample of the huts needed to house the Continental Army at Valley Forge. Subsequent agriculture, industry, infrastructure, and recreation have all led to the disturbance and loss of archeological sites from the Revolutionary War and other time periods.

Yet change is unavoidable in—and instrumental to—the archeological record. The discrepancies between the historic documents and the actual configuration of the encampment show that troops could and did diverge from General Orders. The reuse of common objects like musket balls and iron scraps attests to enlisted soldiers’ resourcefulness and diligence in improving their quarters. By giving weight to what is known about their lives rather than dwelling on what remains uncertain, archeology honors the occupants of the encampment as distinct individuals, not just Revolutionary soldiers.

Resources

Kalos, Matthew A. Archaeology Report: Construction Monitoring at Fort John Moore, Redoubt 5. Valley Forge National Historical Park, National Park Service, 2017.

Kalos, Matthew A. and Elizabeth C. Rupp. Phase 1 Archaeological Survey at Redoubt 5 (Fort John Moore/Fort Greene), Valley Forge National Historical Park. National Park Service, 2014.

Parrington, Michael. Report on the Excavation of Part of the Virginia Brigade Encampment, Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, 1972-1973. MASCA, University Museum, Philadelphia, 1979.