Last updated: June 30, 2021

Article

Mail and the National Historic Trails

Public Domain

Dear William, I Hope We Shall Meet Again

Aside from food and gold, what did a Forty-niner want most once he reached California?

Mail.

After three to six months on the trail —and already homesick— he yearned desperately to hear from home. Is everyone well? Is Baby Lizzie talking yet? How are the crops faring this year? Do you miss me, Beloved?

And he needed a reliable way to send his own letters back to wife, family, and friends who were anxiously awaiting news of their Forty-niner’s arrival in California. They had no way of knowing if he had met death along the trail after sending his last letter, months earlier, from a Missouri River outfitting town or perhaps by military courier from Ft. Kearny, Neb., or Ft. Laramie, Wyo. A lot could happen on the way to the gold fields.

Forty-niner William Swain, of Youngstown, New York, left his sickly wife, Sabrina, and their toddler daughter, Eliza, for the California gold fields on April 11, 1849. Over the summer Sabrina received several letters he posted between St. Louis and Ft. Kearny, and a final one sent from Ft. Laramie that reached her on Sept. 10. She had no further word from her husband for seven months, but she continued writing faithfully to William, praying he was well and trusting that her letters would find their way to him.

while I am writing these lines to you, your body may be moldering back to its mother’s dust from whence it came.

--Sabrina Swain, letter from Youngstown, December 7, 1849

Public Domain

Getting There

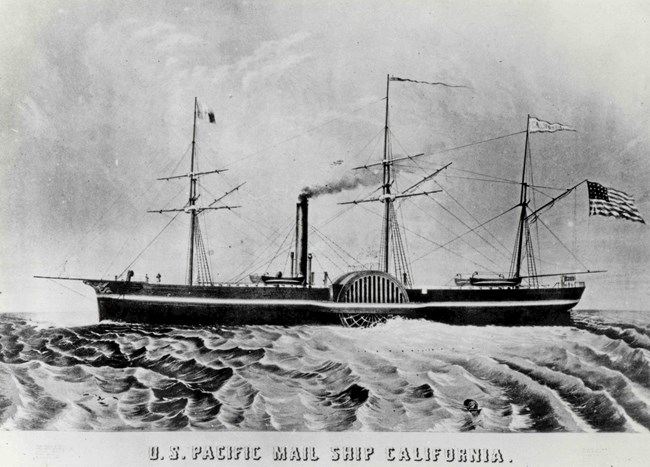

At the beginning of the rush, years before the Pony Express or mail coaches made regular transcontinental runs and before urgent news could fly coast-to-coast by telegraph, most civilian mail went to California by sea. The first U.S. contract mail service between the East and West coasts, starting in 1849, went by ocean-going steamship to Panama, crossed the Isthmus by mule (later, by rail), and continued by steamship up the opposite coast to its destination, carrying letters for about 40 cents per piece. A smooth transit took a couple months, but there could be unexpected, weeks-long delays. Even so, letters posted from the East as late as July could be waiting for a Forty-niner when he reached California in September or October. Such was his fondest hope.

He would be one of thousands—maybe tens of thousands—of arriving gold rushers, all desperate for news from home.

Public Domain

Mail Melee in San Francisco

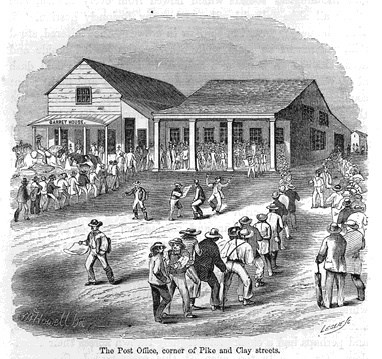

The first US Post Office in California opened in San Francisco in March 1849, amid the initial chaos of the California gold rush. As the Forty-niners flooded into California, so did their letters—bags and bags of them arriving on the monthly mail steamer from the States. After each delivery, the post office closed for two or three days while clerks sorted the mail alphabetically, according to the name on the front of the envelope. Letters would be held there for addressees to come to the windows to pick them up. By October 31, 1849, more than 45,000 pieces of mail had piled up at the little post office at the southwest corner of Pike and Clay.

When the doors initially opened for business, an impatient, rowdy crowd swarmed the place, forcing the clerks to barricade themselves inside their cramped mail room for protection. The hopeful addressees quickly learned to organize themselves into orderly lines that stretched for blocks and “into the tents among the chaparral on the hillside,” according to one source. Lines moved forward at about 40 feet per hour; a man at the rear might wait most of the day, or even several days, in heat, dust, and rain for the chance to receive his mail. Some fellows stayed through the night so as not to lose their place in the queue.

The situation provided entrepreneurs an easy way—easier than digging for gold, at any rate—to earn a living by selling their place in line or by vending coffee, pastries, and newspapers to the hungry, bored miners awaiting their turn at the window.

Picture the joyful grin of the Forty-niner who, having arrived at the window, receives a handful of letters from home! He clutches them close to his chest as he shoulders his way out the door to find a quiet spot to sit, read, and memorize each word on the pages.

Now, imagine standing in line all those hours and at last anxiously saying your name to the tired clerk behind the counter, only to be told, “Sorry, nothing here for you today. Next!”

Men wept.

So, one imagines, did the mail clerks, who not only had to sort and distribute the incoming post but also handle the tens of thousands of letters sent home by the miners. They worked round the clock, napping on the post office floor when necessary.

I have looked for letters until I got tired of asking the postmasters. This is the 15th letter that I have rote to you since I left home and receive 4 letter.

--William Miller, letter home from the gold fields

The Expressmen

One of the difficulties for mail delivery was that miners moved frequently and had no permanent address. They packed out to a “diggins” deep in the mountains, tried their luck, and then moved on to the next promising spot. A side trip to check for mail at San Francisco or Sacramento, where a post office opened in November 1849, wasn’t always possible.

And here was another business opportunity. Enterprising men visited the camps, took down the names of miners working there, and brought back their mail for $1 up to $16 per piece, plus 50 cents to take an outgoing letter back to the post office. Some of these enterprises developed into companies, “western expresses,” that also handled gold and offered banking services. For example, Adams & Company Express would purchase gold dust from a miner and, for a charge, forward the value to an office in the States where the man’s “gold rush widow” could retrieve the often desperately needed payment. The system was efficient and profitable.

The Last Letter Home

Families back home begged in every letter to know when their Argonaut would return to them, and they eagerly awaited word that he had reserved the next available steamer berth bound for the Isthmus. (Nearly all returning miners departed San Francisco by steamer, sometimes a mail steamer. Very few were willing to travel the overland trails from west to east.) The families of some gold rushers waited four, five, six or more years before their loved one returned triumphant, with a pocket full of “rocks,” or humiliated, with nothing to show for his years of hard labor. Some never returned at all, too ashamed to face their families or simply deciding to pursue new opportunities in California.

For other families, the wait, though painful, was not as long. William Swain, for example, quickly quenched his thirst for adventure and hurried home the very next year, a round trip of just 22 months.

I have made up my mind that I have got enough of California and am coming home as fast as I can.

--William Swain, letter home, Nov. 6, 1850

Original letters from the California Gold Rush are archived at numerous repositories across the country, from Yale University (where the Swain correspondence is kept) in Connecticut to the Huntington Library in California.

For Further Reading

- Holliday, J.S. The World Rushed In: The California Gold Rush Experience. University of Oklahoma Press, 2002.

- Mingee, Rick. “The Steamers of San Francisco, 1849-1854,” The Postal History of 19th Century San Francisco. Available at The Steamers of San Francisco 1849-1854 - SFPH (rickmingee.com)

- Putnam, John. “The 1849 San Francisco Post Office,” My Gold Rush Tales, 2011. Available online at The post office in 1849 San Francisco | My Gold Rush Tales.

- Walske, Steve, and Richard Frajola. Mails of the Westward Expansion, 1803-1861. 2015. Available online at Mails of the Westward Expansion - Frajola (rfrajola.com)The post office in 1849 San Francisco | My Gold Rush Tales.

- Western Cover Society. “San Francisco, Gateway to the Gold Fields,” Western Expresses Articles. Available online at San Francisco – Gateway to the Gold Fields – Western Cover Society.