Last updated: January 19, 2022

Article

An introduction to the benthic macroinvertebrate community at Petersburg National Battlefield

The Mid-Atlantic Inventory and Monitoring Network (MIDN) monitors ecosystem health in ten national parks in the Northeast Region. To measure the health of streams and rivers, scientists sample and identify invertebrates living on the bottom of streams. These invertebrates are called “benthic macroinvertebrates.”

Many states and federal agencies use benthic macroinvertebrates to assess stream health and make determinations about whether streams are meeting standards outlined in the federal Clean Water Act. Ultimately, the goal of the benthic macroinvertebrate monitoring program is to provide the best available science so national park managers can better understand and protect park resources.

This brief provides an introduction to benthic macroinvertebrate communities at Petersburg National Battlefield. This information includes a general description of benthic macroinvertebrates and, using data from 2009–2018, a summary of macroinvertebrate community characteristics in the park.

The brief does not address the question of stream ecosystem health — future publications will fill that important role.

So, what are benthic macroinvertebrates?

Benthic macroinvertebrates are invertebrates that live on the bottom of streams and rivers and are visible to the naked eye. They include a large number of taxonomic groups. Macroinvertebrates are useful for ecological assessments because their communities can change dramatically at varying levels of pollution.

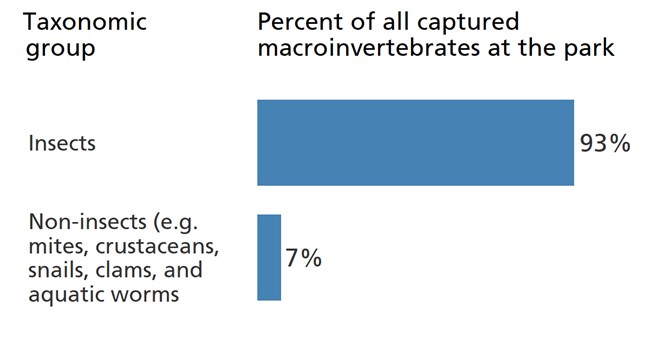

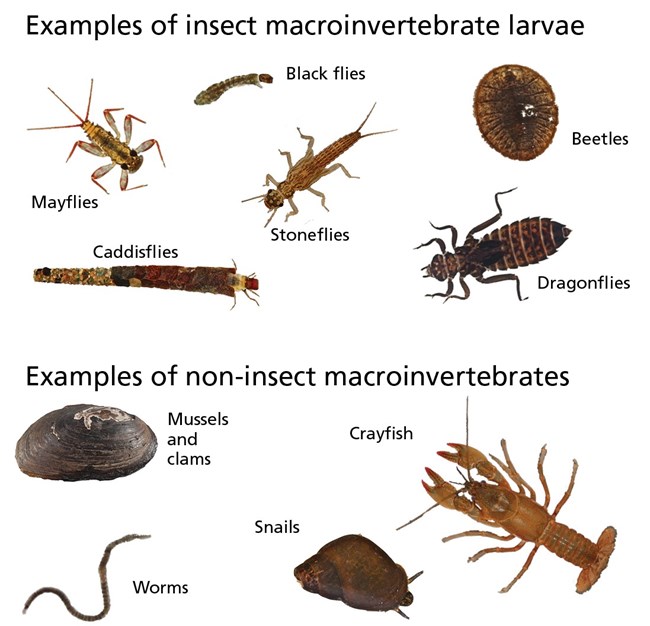

Most benthic macroinvertebrates captured in streams at the park are insects. These include the larvae of many common groups like mayflies, caddisflies, stoneflies, and the true flies. Other macroinvertebrates that aren’t insects are also present.

Images not to scale. Photos are just examples of macroinvertebrates and do not necessarily represent specific taxa found in the park. Photos courtesy of J. Gallagher (dragonfly larvae), the Smithsonian Institution (mussel and crayfish), Willamette Biology (worm), and B. Henricks (all others) / Flickr.

What is the most common macroinvertebrate in park streams?

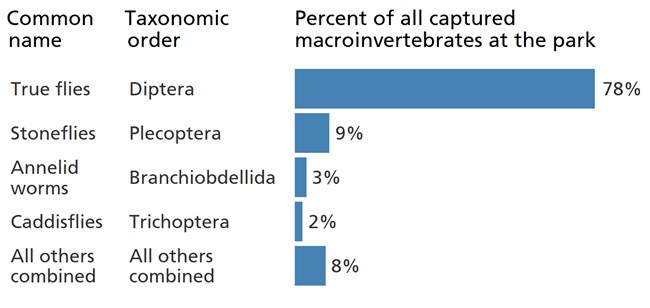

Well over one-half of the benthic macroinvertebrate observations from the park are in the taxonomic order Diptera and are known as “true flies.” True flies include insects like mosquitoes, deer flies, crane flies, and midges. True fly larvae are abundant in streams across the mid-Atlantic region.

Stoneflies are the next most common macroinvertebrate at the park. Stonefly larvae can live in streams for several years before maturing. After maturing, they hatch into flying adults who mate and die, often in a matter of weeks.

Which macroinvertebrate group is the most diverse (has the largest # of species or genera)?

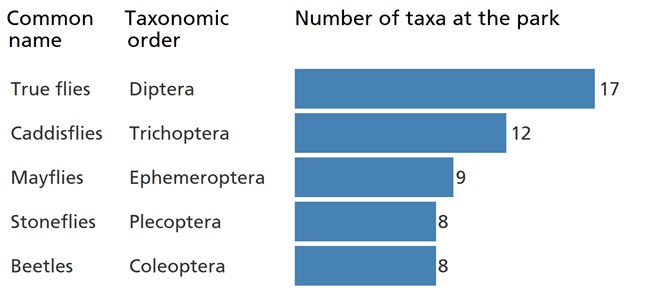

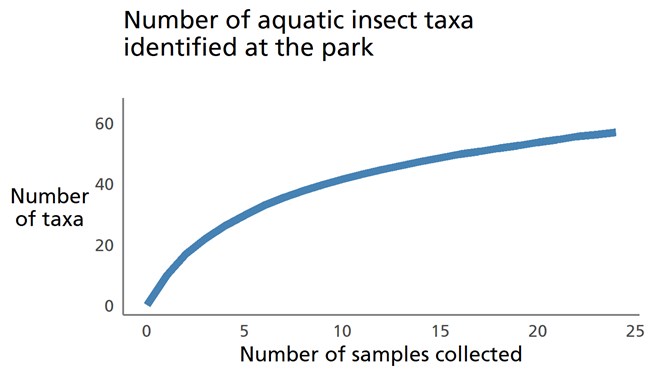

A total of 81 taxa have been identified at the park (including 63 taxa of insects). The top two most diverse groups are true flies and caddisflies. With benthic macroinvertebrates, most individuals that are insects are identified to the genus taxonomic level. Non-insect macroinvertebrates are often not identified below the family level, and therefore, non-insect diversity (not shown) is not as well documented.

What's next with benthic macroinvertebrate monitoring?

Benthic macroinvertebrate monitoring efforts continue to focus on measuring the health of stream ecosystems in the park. These data help managers understand the condition and trends of park streams and identify potential stressors to these valuable resources.

Click here for a printable pdf of this article.

For more information about this program, visit the MIDN macroinvertebrate website, read the latest summary report, or contact MIDN Ecologist Nathan Dammeyer.

To learn more about benthic macroinvertebrates, including how to identify them with some stunning images, check out the online Atlas of Common Freshwater Macroinvertebrates of Eastern North America.