Last updated: April 7, 2025

Article

Low, Light and Livable: From Modern to Ranch in Arkansas, 1945-1970

Weyerhaeuser

Introduction

Holly Hope: I really am honored to be included in an agenda with so many people who are much more lofty than I. I have learned so much so I want to thank you and then I better get into it.

I’m going to go over the bureaucratic and social reasons for the emergence of the Mid-Century, Modern and Ranch in Arkansas. In particular I want to touch on the role of women in Mid-Century house design.

Architecture of the home was always family centered, but it wasn’t always designed according to the convenience of the women of the family. Cultural movements eventually began to consider the real needs of women within the parameters of family life, but it wasn’t until the mid-century that the female perspective was sought out and their contributions physically influenced the form of the house. Not necessarily as architects, because female architects were all but unknown in Arkansas at the time, but rather as an every day inhabitant of the house.

Forward Looking Forms

Modern and Ranch type homes were forward looking forms. They evolved from the craftsman bungalow and historic revival styles. It was logical that women were eventually instrumental in their design because ideas about the roles of women were evolving in the mid-century as well. Ranch architecture was promoted heavily as the home of choice in 1950 subdivisions for young families. Modern and Ranch co-existed but large scale developers could see that the Ranch form lent itself to prefabrication and quick construction in large numbers.

Government agencies were hesitant to finance modern houses in the beginning because they were out of the norm. As a result the Ranch became a prevalent style that was reproduced in many sizes and forms in Arkansas subdivisions for decades. The Ranch shared architectural characteristics as well as the attitude of modern architecture and it evolved from that style as it quickly overshadowed it in Arkansas.

Precedence for the minimalistic trends of mid-century modern and ranch surfaced at the close of the 19th century when the fussy Victorian era was abandoned for simplicity and balance in exterior and interior treatments of homes. Central to this was the comfort of the middle class family. Previously the domestic unit consisted of the stay-at-home mother under the authority of the hands-off father. She would serve as the supervisor of the children in the house.

By 1910 technology and economic growth allowed for a shift women’s roles. They started exploring new life purposes outside the home and this trend led to the popularity of straight-forward architecture with less furniture, fewer rooms and reduced maintenance. These were all hallmarks of the modern and ranch houses to come.

During the Progressive Era in 1880 – 1920 honesty because a frequent catch word. This referred to casual beginnings and a return to a more humble environment in a smaller house, the Bungalow, which was constructed with natural materials and authentic textures. Similar to the tracts of ranches in the 1950’s neighborhoods, the bungalows furthered changes in social conventions.

Starter Homes for Young People

These small homes were considered appropriate for young people who were just beginning their lives. They were starter homes, just like those that were embraced by couples after World War II. Hearty, comfortable spaces and furniture invited the enjoyment and participation of children as active members of the household. The explosion of mid-century subdivisions in Arkansas was a continuation of 1920 suburban expansion of bungalows buoyed by the federal government.

Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover encouraged efforts to increase housing stock by using the federal government to stem shortages. With the support of the government, the Architect Small House Service Bureau formed in 1921 drew up house plans at a modest price and assisted in classes on do-it-yourself construction projects.

Hoover instituted the own-your-home campaign to aid war industry workers in purchasing houses through long-term mortgages. He was also a supporter of the 1923 Better Homes in America Incorporated program which sponsored tour houses in rural and urban areas to promote owning and maintaining a home during Better Homes Week.

In Arkansas White and Pulaski counties participated in Better Homes Week during the early 1930’s. Clytice Ross, 1931 White County, Arkansas, Better Homes Incorporated Chairwoman and Home Demonstration Agent reported that Littlerock had hosted a Better Homes school, County Better Home schools and District Better Homes schools.

These all provided ideas for various campaigns during Better Homes Week. Reports from these campaigns resulted in prizes for activities that encouraged thrift for home ownership and to help make accessible to all American families homes of beauty, comfort and convenience. These activities were primarily facilitated by women. Females made up committee heads and volunteers because that was logically their area of experience.

Government programs like these were designed to install the proper mindset for home ownership. Eventually encouragement moved to actual involvement and fiscal assistance for potential home buyers. The first steps had been taken by Hoover in 1930 when he held the President’s Conference on Building and Home Ownership which supported bank loans for homes, among other things.

The Federal Housing Administration allowed developers to obtain bank loans for subdivision of land and construction of houses, which became a more lucrative process for the developers by the post World War II era.

Forest Products Laboratory

Federal Housing Administration (FHA) & Subdivisions

Technical bulletins distributed by the FHA provided guidelines for subdivisions. The agency recommended in 1939 that development should reflect a cohesive sense of community that allowed each occupant to take a proprietary interest in maintaining their home. This had the effect of promoting long-term mortgage security.

As early as 1936 the FHA addressed the suitability of modern design. The agency exhibited a degree of tolerance in such houses but they left the option open for denial in their technical bulletin Addressing Modern. It was noted in FHA circular No. 2, Property Standards, that there was nothing that would outright disqualify Modern Design for insurance, but it was still subject to risk-rating procedures.

The FHA stated that a house might receive a low property rating if the design was so far left of the norm of acceptable houses and how great the departure was in the direction of public receptivity or anticipated receptivity. Also architectural inspectors might not be able to divorce their own feelings about the appropriateness of the house style while conducting architectural attractiveness rating assessments. Consideration for adjustment for non-conformity might determine that a modern house was too non-conformist to fit into an established neighborhood of more traditional design.

The FHA eventually accepted that this architecture was not fleeting and by the end of the 1950’s agency standards were updated to give modern designs at least a chance. However, in the long run its own uniqueness prevented modernism from being widely used in subdivisions in many areas of Arkansas. Compared to the ranch, the numbers of modern house forms in the state were definitely on the low side. By the 1940’s FHA standards included the stipulation that older neighborhoods were not eligible for assistance which is a clue to the charactering spread of Mid-Century subdivisions outside of the traditional city court.

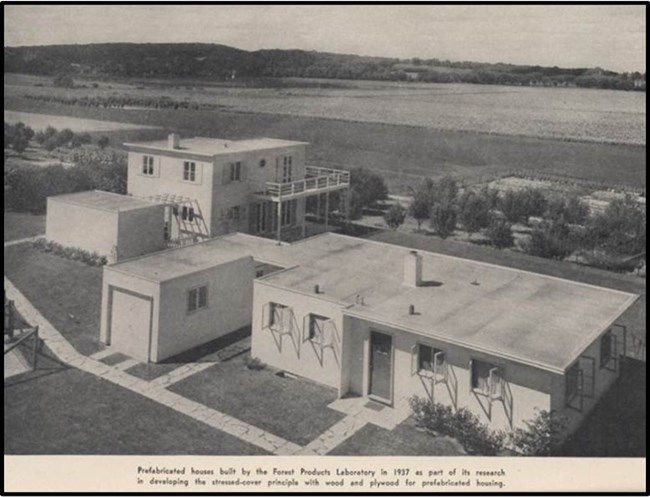

In the 1950’s government aid and the post-war housing need combined to change the way developments were constructed. At that time developers didn’t just sell lots, they also built the homes. The increased use of prefabrication for war housing in industries led to its acceptance for mainstream residential design. Prefabrication used in home construction was touted as a fast and economic method of building and it soon because wildly popular, resulting in houses that imitated the rational forms of modernism with smooth surfaces, flat roofs and asymmetrical window placement.

This new look in home building inspired building material and appliance industries to heavily promote modern residential design in the 1940’s. Advertisers in home builder’s magazines would showcase their new, technologically advanced products within a functionally spare modern setting. Promotion techniques like these conveyed the idea that Americans were part of a progressive economy and instilled them with the confidence that post-war life could go nowhere but up. Architecture journals and women’s home magazines included modern backgrounds for advertising and features which helped plant the idea that modernism might be socially acceptable, but in reality traditional forms held on for many years.

There were still camps in the 1940’s that couldn’t stomach that extreme example of modernism and despite the growing attention to modernism, Mary Gillies of McCall’s Magazine cautioned in her 1945 report, Let’s Plan a Peace Time Home, that early functional planning went too far. In her opinion the move away from the usual led to a trend toward houses that had beauty for a surrealist. She stated that the neighbors called them monstrosities and she referred to modern homes as a fad.

Arkansas Historic Preservation Program

Resistance & Red Tape

There were also still bureaucratic roadblocks to getting modern homes on the ground, the spread of novel residences was hindered by the fact that local building regulations in many areas did not commonly approve new building techniques or materials. The FHA’s early take on the term modern referred to a new way of live, revolving around consumerism and updated technology in home furnishing, appliances and utilities, instead of architecture.

Distinctive modern architecture was usually favored by clients who wanted their homes to reveal the economic or social standing. They weren’t interested in fitting in and being inconspicuous. Fear of this unorthodox mindset could reasonably be a factor in why the FHA stuck with conservative design and gave modern buildings low rates on adjustment for conformity, because people with those attitudes would hurt mortgage security for everyone.

However, FHA standards were basically upgraded in 1958 allowing for home builders to choose modern or revolutionary architectural techniques. Small middle class examples of modernism in Arkansas were more often mixed into a subdivision so that the developer could please everyone.

The term modern regarding mid-century architecture was kind of amorphis in Arkansas. It could be used to described academic examples of modernism, or to describe any ground breaking architecture, the ranch included. Sales campaigns for new homes in mid-century Arkansas referred to many examples as modern, even if they had tipped roofs, double hung windows and clapboard siding.

Contemporary was a phrase used often in real estate advertising to describe what could be considered minimally populous modern. Ads for Meadow Cliff subdivision in Littlerock stated that you could choose traditional, ranch or contemporary house plans. Mid-century modern tentatively stepped into Arkansas subdivisions, but there’s only a few identified areas that contain a large concentration of this style.

Architect Ian del Johnson known for his strikingly modern commercial structures in Littlerock contributed to Miramar and Meadow Cliff subdivisions with small homes that exhibited non-traditional traits like shallow gables or shallow roofs and asymmetrical fenestration. These homes would definitely fall into the contemporary/populous modern categories rather than traditional or typical ranch forms. These are not Ian Del these are just other examples.

By 1959 houses showcased in the women’s section of the Arkansas Gazette began to include more innovative designs in modern forms but still those numbers didn’t reach the level of ranch examples. The reasons for the lack of subdivisions in Arkansas exhibiting modern character were sometimes governmental or cultural but also practical on the part of the developers.

Introducing modernism into neighborhoods wasn’t always so easy to implement on a large scale. In contrast to modernism, the ranch could be translated into small, economical units that could be quickly constructed by a developer or spread across the division by an architect utilizing the panoply of ranch characteristics on a small scale.

Eventually the influence of modernism melded with the ranch in the use of glass, elimination of exterior ornament, and incorporation of the outdoors with the interior, as well as the use of exposed structural elements; you kind of had the best of both worlds.

Arkansas Historic Preservation Program

American Ranch Rorm: Nebulous & Malleable

The appeal of the American ranch form was that it was nebulous, it was malleable, its purpose was easy-going living, more so than a prescribed presentation. Even as it spread across the nation and was mass produced, several sub-types emerged. In some instances historic architectural influences were minimally articulated.

In Arkansas most of the influences were Colonial Revival, which was also referred to as Traditional by realtors, or they were straight forward minimal with typical picture window, wrought iron porch posts and interval planters. Some Arkansas ranch homes in the late 1950’s were described as Gaelic or French Provincial. The storybook form with faux half timbering, birdhouses applied to the gables, strap hinges and diamond pane windows were also found in minimal members.

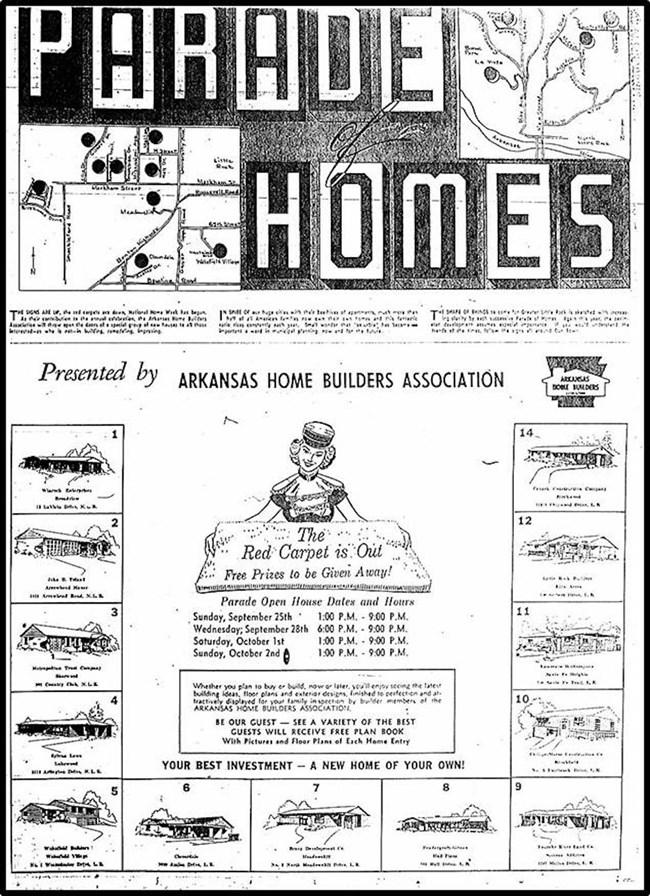

Subdivision growth continued throughout the state in the 1960’s but the ranch seemed to become more compact and it eventually developed an identity crisis. The 1962 parade of homes included houses built in contemporary, traditional, Cape Cod, French cottage, Cape Cod/Texas Ranch, Colonial and Transitional. These are really more or less all the same, but they trended less toward the prowling modern form.

Headlines never let Arkansans forget that the ranch seems here to stay. Developers wouldn’t let the Arkansans forget either. Prods from the realtor sections of the paper were heavily supplemented by marketing methods like model homes that were landscaped and furnished with the latest conveniences. Once the family made the trip over to look at it and then they went home, the comparison serves to make them see their own home as rather scruffy. It immersed them in that environment and it allowed them to feel as though yes, they could have this too.

Other techniques to draw customers to open houses were a talking Nash Airflight Car parked in the drive of homes to greet the customers. It quoted prices and told them about the modern features that they were going to see. An X-ray house would utilize hole in the exterior to demonstrate the construction method, insulation and heating systems. Home building shows like the compare-a-rama at the Barton Coliseum in Littlerock featured home building vendors with new products and appliances that the family could see and touch.

Beginning in 1952 the Annual Parade of Homes would present a tour of 12 new houses in the latest ranch forms. Arkansas home buyers were inundated with the ranch through the use of these psychological manipulations. These techniques were also employed during Word War II when housewives were encouraged to start dream books for their new home. In 1945 McCall’s magazine counseled that families shouldn’t decide on the architecture of their home first, but instead take the modern, scientific route and start with the inside.

Arkansas Historic Preservation Program

Configurable

The Arkansas housewife was addressed by the State Chapter of the American Institute of Architects in the 1952 Parade of Homes book. The AIA stated that when you know very little about something you aren’t very critical. They instructed the female that she should take into account livability, site planning, circulation, privacy and storage space when she was choosing a new home. This was an important indicator of the new trend of adaptability, beginning with the interior footage.

The possibility of expansion was important to young families and the inside was now the Nexus and the character of the family. The human factor ultimately dictated the spaces. The interior offered more of a glimpse into the mid-century family relationship through the floor plan, the numbers of rooms, their uses and inventive methods of storage and lighting.

Rooms could be simply transformed for different uses through a new furniture arrangement. It was easier to introduce changes to rooms in a one story house like the small modern and ranch. Fresh interior arrangements deleted warns of rooms and opened the houses by eliminating walls. This was progressive space that could be enjoyed by every member of the family.

The precursor of the growing influence of women in these changes could be seen during World War II as the opinions of women on house needs and forms were increasingly sought after. In 1944 McCall’s magazine held contests for war bonds that resulted in four reports. What women want in their living room’s of tomorrow, their dining rooms of tomorrow, their kitchens of tomorrow and in their bedrooms of tomorrow.

The last report included statistics on what kind of house the participants would like to build or buy. The two choices were traditional and modern. This is not the modern of the wounded dove roof line, the modern camps stated preferences were corner windows, built-in storage, uncluttered rooms that were easier to clean and a balance of masculine and feminine décor- all traits that eventually came to characterize the ranch. Mary Gillies had to eat her words when the survey revealed that 2,046 contestants stated that they wanted to have a modern house built to order, rather than a traditional one. That’s Mary in the report there.

Developers and builders knew that the women of the house in most cases had the final say on what form the new house took. The building of enthusiasm in the female population and the presentation of a perceived need was used efficiently by Arkansas developers and realtors. Features on housing styles were located in the women’s section of newspapers through the 1950’s. Every Sunday The Arkansas Gazette Women’s Section would feature a new home with photos of the interiors. The woman of the house was usually photographed alone in the living room or the kids would be posed in the bedroom. Typically dad was nowhere in the picture. Home styles were the territory of the wife.

Science began to back up the influence of women into architecture even if it didn’t stray far from the accepted opinion of their place in society. The University of Michigan undertook a 1947 study on the sociological impact of house size and space arrangements. The goal of this was to determine the level at which a house became unhealthy and unsatisfactory to family life. A main concern was how large the house could be before the housewife became fatigued while working outside the home and caring for children, cost per room and the amount of housework needed to maintain them were benchmarks.

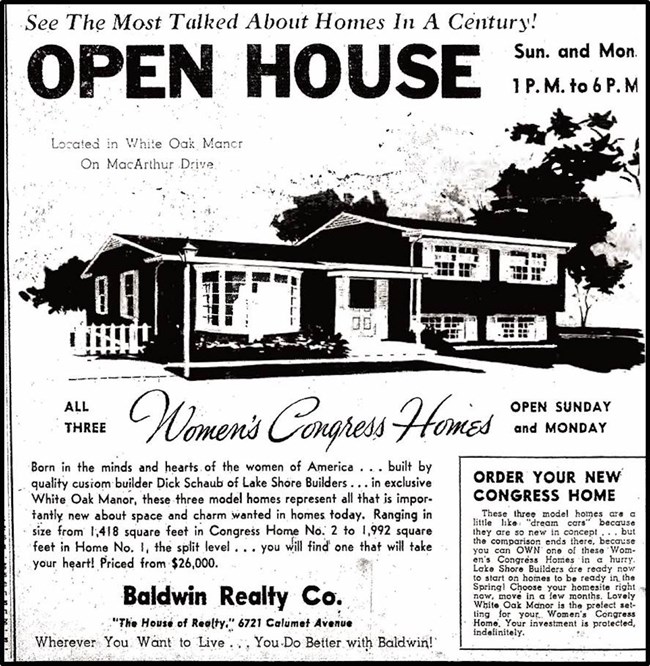

The passive role of women as lab rats for housing trends evolved to actual implementation of female ideas and needs in house designs. In 1956 the Housing and Home Finance Agency hosted 103 women in Washington D.C. for a Women’s Congress on housing. They were asked to offer their thoughts on single-family home design for the interior and exterior.

The Congress allowed women in a limited way to relate what they thought builders and architects were doing wrong in design, and their contributions were applied to three dream homes constructed in 1956 in the ideal mid-America location of Munster, Indiana.

The majority of the participants in the Congress expressed a preference for one story homes, but there was one split level. Fifty nine features included in each house expressed what the women felt would make life psychologically, economically and strategically better. Their thoughts were validated by a total of 3,500 people who came from across America to view and tour the homes.

All of these features were enveloped in ranch style forms and they expressed the new precepts of mid-century life, including efficient use of space, open forms and segregated public/private and adult/children areas. While the interiors were considered cutting edge, the exteriors were reported as presenting nothing new, just the standard ranch built around activities and family values rather than pretty architecture.

Arkansas Historic Preservation Program

Parade of Homes

The successor to the Women’s Congress was McCall’s 1957 Congress on better living. Despite a trend toward individuality that evolved away from acceptance of the usual, they still wanted a home that conforms to the neighborhood image, nothing flashy. Informal, convenience, easy going, efficiency and livability. These were catch words used in realtor ads and home magazines to describe the ranch phenomenon.

California Ranch designer, Cliff May’s theory was that the ranch house should be easy to traverse with an open flow, unencumbered with steps and the outdoor areas should be on a plane with the house. This became a symbol of the informal character of the mid-century family. This layout really played into the hands of the mid-century woman.

Ian Dale Johnson’s wife, Mary, stated in 1952 that women were inherently lazy therefore movement through the house should stem from a single central hallway with radiating rooms to provide an efficient circulation pattern for chores. Some house forms could be multi-level but the movement of interior space was free and not confined by steep, enclosed staircases or hallways. Women had been considered in the arrangement of rooms in earlier house forms, but it consisted primarily of making it easier for them to circulate in the kitchen. When they were featured in realtor advertising or mail order home catalogs, they were in the kitchen or they were taking a bath.

By the 1950’s the female was ostensibly liberated by advertisers for time saving appliances but at the same time interior arrangements concentrated around how mom could be in the kitchen and still be seen by the family. The seemingly primary location of mom, the kitchen, was evolving as a consequence of women’s new role in the family and the world. Home building and decorating magazines heavily emphasized the design of the kitchen.

In 1953 author Robert Woods Kennedy stated that the housewife cannot be expected to enjoy cooking as long as it is thought of and expressed as a duty which interferes with life, it must be a part, an important part, of life itself. Architectural record had suggested that the absence of servants and the access of guests to the kitchen dictated that it be divorced from its reputation as a room for drudgery. It should be a center for family and social life, combining it with the dining room and living room. Mom was at the helm of the kitchen. In the mid-century floor plan she could participate actively in home life while still getting the job done.

Pass-throughs and strategically placed windows allowing for supervision of the kids as well as its juxtaposition to a family room or living room gave the kitchen the new designation work center, or living kitchen.

In the mid-century more consideration was being given to the mental development of children. It became important to provide bedrooms for each child, as well as informal family rooms. Kids could learn from their interactions with adults and visitors in the family room and then take their life lessons in respect and responsibility to their bedroom. As Laura said, the women who participated in the Women’s Congress on Housing, felt that the bedrooms should be separated from the family areas for quiet and privacy.

The rectangular one story ranch or modern lent itself to creating active zones and quiet zones. The parent’s bedroom or the master bedroom with associated master bath emerged in larger houses. This adult area usually included the formal living room which created a space for dad to get away from the kids and it allowed for adult interaction between the parents. These configurations emerged because of the economic sensibility of a mid-century house and the expression of the family dynamic.

Arkansas Historic Preservation Program

Buying stuff, of course, we know this was a primary project for the housewife. The automobile became an enabler of this. After World War II the car was proclaimed a necessity of life by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. In 1957 Redbook Magazine encouraged living by the automobile in the age of the push button. The magazine sponsored promotions called Easy Living and Happy Go Buy It to young suburban families.

By 1954 road improvements were enabling Arkansas developers to bring their families to the subdivisions and tied to this national trend of bringing goods to the people would work in their subdivisions in Littlerock and it would also encourage home sales. Servants didn’t do the shopping anymore, the housewives did it and an associated shopping center became an expected feature of new development with hooks aimed at women.

Shopping centers were also supported by the fact that by the mid-century American women were becoming more active outside the home. Before World War II the number of women in the American labor force was over 10 million. By 1950 it had risen to over 18 million. In 1950 female employment in Arkansas was up 14.2% from 1940. Family spending jumped with the increase in income provided by working mothers. The growing number of families purchasing single family homes fueled consumerism and even though more women were working, merchandisers knew that home was still the domain of the female. Cultural documentation of the mid-century reflected that women were the force behind housing styles and needs and they now had more power through increased earning opportunities.

The home was always the calling card of status and the family but by the 1950’s it truly projected the honesty of the progressives as the face of the family and the neighborhood. Part of this honesty was the characteristic of individuality, which the women of the Congresses concluded was the proper form for the house, not an across the board plan. Popular culture and the opinions and the solicited ideas of women became significant to the form of the mid-century house and it became a symbol of all things to all people.

Thank you.

Abstract

This multiple property context examines the advent of Mid-century Modernism and how it resulted in the iconic Ranch form in Arkansas during the period from 1945 to 1970. I outline the convergence of Modernism and the popular Ranch form by examining the bureaucratic, social, cultural and economic factors that contributed to significant transformations in domestic architecture. The context looks at the historic international and national architectural foundations of Mid-century structures and sociological reasons such as the Progressive movement, for the widespread acceptance of a dramatically altered house form.

I use a mix of books, government documents and Mid-century newspaper and magazine articles and advertisements to analyze the human forces behind Modernism and the Ranch. In particular, I follow the contributions of women to the design of the Mid-century home through gradual changes in family dynamics and popular culture. Evidence of the impact of women on the house form is gathered from their participation in movements like Better Homes, Inc., Women’s Congress and Congress on Better Living.

Such movements threw light on the fact that women were influential on house design without actually drawing up plans or being given credit until the 1950s. The solicitation of ideas from the sector of society who spent the most time in the home was key to groundbreaking architectural and neighborhood planning transformations.

Speaker Biography

Holly Hope has worked at the Arkansas Historic Preservation Program since 1997. She was National Register Survey Historian from 1997 to 2000. From 2000 to the present she has served as Special Projects Historian. Her duties include writing multiple property contexts, National Historic Landmark nominations, National and Arkansas Register of Historic Places nominations and serving as the cemetery liaison for the state’s constituents. Hope received her Bachelor of Arts in History from the University of Arkansas at Little Rock.

This presentation is part of the Mid-Century Modern Structures: Materials and Preservation Symposium, April 14-16, 2015, St. Louis, Missouri. Visit the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training to learn more about topics in preservation technology.

Tags

- gateway arch national park

- ncptt

- mid-century modern

- mid-century modern structures

- st. louis

- ranch type ramblers

- ranch house

- houses

- weyerhaeuser

- forest products laboratory

- prefabricated

- holly hope

- arkansas

- parade of homes

- women’s congress homes

- federal housing administration

- fha

- arkansas historic preservation program