Last updated: December 2, 2024

Article

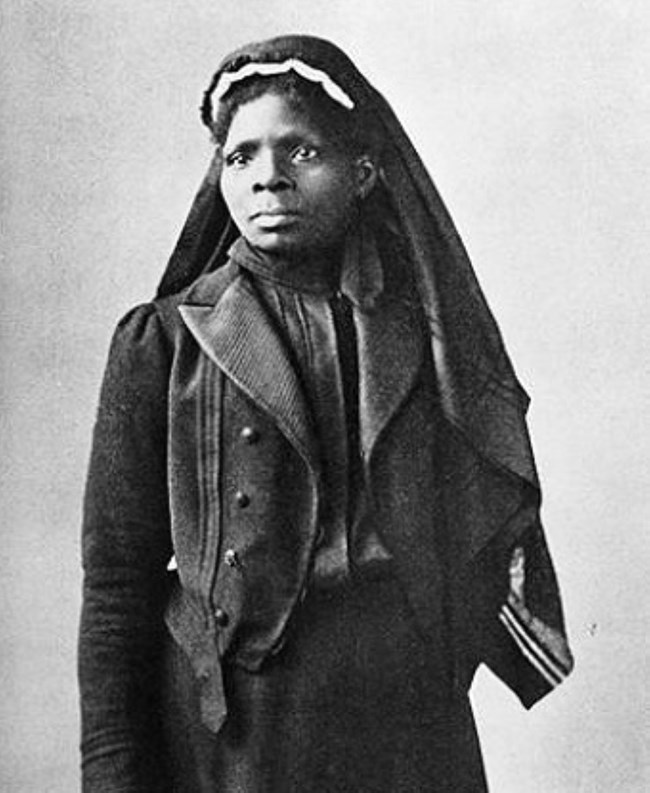

Lift Every Voice

Library of Congress

Childhood

For Susie King Taylor, being born under Georgia’s slave law meant she was not her own person, but instead the property of another. It meant she was restricted in where she could go and when she could go. It also meant she was forbidden to learn to read or write. All across the South, including in Savannah, many people feared that educating enslaved people would lead to them losing their control and power, and so it was against the law for an enslaved person to learn how to read and write. From a young age, Taylor rebelled.

Encouraged by her grandmother, Taylor attended two schools in secret run by Black women. Here, she learned to read and write. “We went every day about nine o’clock, with our books wrapped in paper to prevent the police or white persons from seeing them,” she remembered. With her illegal education, Taylor often wrote passes for her grandmother, as all African Americans—enslaved or free—were required to have a pass in order to be out past nine o’clock at night or else be arrested.

As 1861 arrived and the Civil War began in earnest, Taylor began longing for something she had never known: freedom. “I wanted to see these wonderful “Yankees” so much,” she recalled, “as I heard my parents say the Yankee was going to set all the slaves free. Oh, how those people prayed for freedom!”

Escape to Fort Pulaski

In April 1862, Confederate-held Fort Pulaski fell to Union forces. Only a day after the battle, Union General David Hunter issued General Orders No. 7 in which he declared that all enslaved people on Cockspur and Tybee Island to be free. While this order did not extend to the still fiercely Confederate city of Savannah, it did provide a beacon of hope for many enslaved people in the area who believed that if they could just make it to Cockspur Island, then they would be free.

Only two days after Fort Pulaski fell, fourteen-year-old Taylor and her family took their freedom into their own hands and escaped to the waters surrounding the fort where they “landed under the protection of the Union fleet.” Taylor was only one of several hundred formerly enslaved people who took it upon themselves to seek out their own freedom by escaping to Fort Pulaski.

Many of these people remained on Cockspur Island throughout the war, taking up residence in the old construction village that stood near the modern-day parking lot. Others, however, chose to leave Cockspur Island and travel further north. Susie King Taylor chose to leave Savannah and go to the South Carolina Sea Islands, where “at last, to my unbounded joy, I saw the “Yankee.”’

Library of Congress

Laundress, Nurse, Teacher

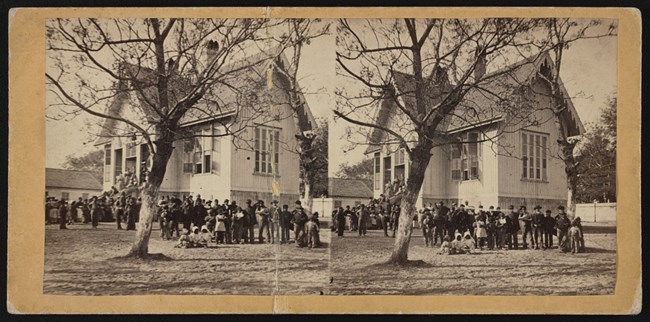

Upon reaching the Sea Islands, Taylor found work as a nurse and laundress for the 1st South Carolina Volunteers, one of the first infantry units to be comprised of formerly enslaved men. This unit was soon redesignated as the 33rd Regiment United States Colored Troops (USCT), and Taylor spent the next four years with these men in her role as a nurse and laundress. Another role soon called to her, however, that of teacher. “I had about forty children to teach,” she recalled in her memoir, “besides a number of adults who came to me nights, all of them so eager to learn to read, to read above anything else.” For several months she remained at her school, teaching both young and old alike to read and write. She received no pay for her teaching work, but she “was very happy to know my efforts were successful in camp, and also felt grateful for the appreciation of my services.

When the 33rd USCT was sent away from the Sea Islands, she followed them officially as a laundress, but most often as a nurse. She cared for the soldiers when wounded or sick, even coming under fire herself during several engagements.

Library of Congress

After the War

When the war came to an end, Taylor returned to Savannah with her husband, Sergeant King, who had served in the 33rd USCT. Shortly after settling into their new life, Taylor opened a school in her downtown home for African American children. She had twenty children in this first school who each paid $1 a month for their education. In addition, she also taught a few older children who stopped by her home at night. Unfortunately, this school lasted only about a year before a free public school opened and she lost a number of her pupils. To add to the hardship, her husband died shortly before the birth of their child and she was forced to give up teaching only a few months later.

Despite these hardships, however, Taylor persevered. Seeing few opportunities for a teacher in Savannah, she moved to Liberty County, Georgia, where she opened another school. After a year of teaching and living in the country, however, she decided that country life was not for her. So she returned to Savannah where she opened a night school with the intention to teach adults how to read and write. Only a year later, however, a free night school opened and, once again, Taylor was forced to close her school and find work elsewhere.

Finding work with various families, Taylor realized that Savannah did not hold opportunities for her. In the 1880s, she left Savannah for good and moved north, to Boston, Massachusetts. There, she met her second husband and devoted herself to the Women’s Relief Corps, an auxiliary to the Grand Army of the Republic which cared for Union veterans. “My hands,” she wrote, “have never left undone anything they could do towards their [Union veterans] aid and comfort in the twilight of their lives.” In 1902, she set about recording her memoir, titled Reminiscences of My Life In Camp With the 33rd United States Colored Troops Late 1st S.C. Volunteers, in which she told of her wartime experiences.

Though her memoir spends quite a bit of time detailing her experiences during the Civil War, Taylor also spoke of conditions at the turn of the century. “In this ‘land of the free,’” she wrote, “we [African Americans] are burned, tortured, and denied a fair trial, murdered for any imaginary wrong conceived in the brain of the negro-hating white man. There is no redress for us from a government which promised to protect all under its flag.” In 1898, Taylor travelled to Louisiana to care for her sick son. She attempted to purchase a ticket for him in a sleeper car, but she was denied because of the color of her skin. “It seemed very hard,” she recalled only a few years later, “when his father fought to protect the Union and our flag, and yet his boy was denied, under this same flag, a berth to carry him home to die.” “In 1861 the Southern papers were full of advertisements for “slaves,” but now, despite all the hindrances and “race problems,” my people are striving to attain the full standard of all other races born free in the sight of God, and in a number of instances have succeeded. Justice we ask,--to be citizens of these United States, where so many of our people have shed their blood with their white comrades, that the stars and stripes should never be polluted.

Legacy

Susie King Taylor died in Boston on October 6, 1912, at 64 years of age. She was buried in Mount Hope Cemetery, and while she died in relative obscurity, her legacy lives on. Her memoir remains one of only a few reminiscences of life in the United States Colored Troops, and one of only a handful of memoirs written about that time period by an African American woman. In 2018, Taylor was officially induced as Georgia Woman of Achievement, which recognizes women who have made significant statewide contributions to Georgia society.

Throughout her life, Taylor experienced hardships that would have stopped many people in their tracks. But she never stopped. Through slavery, through war, and throughout all of her life, Taylor persevered and fought on. Her strength, dedication, and tenacity continues to inspire people to this day.