Last updated: June 16, 2021

Article

Indigenous Artistry: Leonard Harmon

Leonard Harmon

This article was originally published Febuary 22, 2021 on FindYourChesapeake.com.

Leonard Harmon is a Native artist and citizen of the Lenape Tribe of New Jersey and the Nanticoke Tribe of Delaware. He currently resides in Virginia. Leonard has sung and given dance performances at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C. He has a passion for food, music, art, and dance. Later in his career he started creating art, and he has made pieces for several museums. Currently, Leonard is working on a big project and exhibition for the Camden Historical Society in Camden, New Jersey. Harmon is known for his pine needle baskets and pine needle necklaces. He also makes woodland bonnets to replicate original American Indians’ bonnets. Leonard has discovered how to fade an arrangement of colors throughout the pine needles, and uses synthetic thread and natural materials when making his pieces.

Both tribes’ ancestral homelands were once part of the Chesapeake region and within the Chesapeake Bay watershed. Due to colonialism and colonization, the tribes were forced off their ancestral homelands and forced to relocate. The Nanticoke Tribe of Delaware wishes to keep their cultural identity intact and protected, and are recognized by the state of Delaware. The Nanticoke Indian Association is located in Millsboro, Delaware. The Lenape Tribe is considered the “parent” tribe of other Algonquin tribes and so were given the title “Grandfather."

Leonard Harmon

What inspired you to get started in art?

I have always made art my whole life, but I really got started in 2010-2011. That is when I pushed the hardest to create my art.

My father, Linden Harmon, used to make furniture and put an Indigenous spin on it. All the furniture that he used to create was geometric. He would paint eagle feathers on the top of it. I would watch my dad all the time and my namesake, my Uncle Leonard Harmon, who was a well-known artist. He was known for painting portraits of people on the boardwalk in Rehoboth Beach, Delaware. His artwork started to get featured in the Heard Museum in Phoenix Arizona – an American Indian art museum. I have that direct bloodline to art.

What is your background? What have you studied?

I attended Johnson & Wales University, which is one of the best culinary schools in the United States. Culinary arts was what I primarily went to school for. I was also involved in the music culture and was a well-known DJ at one time. Before my daughter was born, I traveled around the U.S. playing 45’s and worked in a well-known record store in Richmond, Virginia. I was focused on expressing myself through food and music – art wasn’t my focus at that time. Watching my parents and grandparents making meals and growing up in a cooking household inspired me to get into cooking.

Can you dive deeper into the anthropological side of the artwork? What are some pieces or exhibits that you would like to make in the future relating to anthropology?

I am really interested in pre-contact history and pre-contact time period. The pre-contact art focuses on what our ancestors' original livelihoods looked like and the materials that were used. You don’t really see a lot of that anymore. I learned a lot from Iap Gibson, curator at the Wampanoag native home site and his wife, Kerri Helme, who was formerly a manager at Plimoth Patuxet in Massachusetts. The items that they make for the Indian village are all pre-contact and what was used before colonialism. Pre-contact artwork, as well as modern art, are what I would like to get into the most.

What is your source of inspiration when making your art?

I get my inspiration from my ancestors – my father, my grandmother, my mother. Also, when I look at my daughter, I get inspiration from her, too.

Leonard Harmon

With parents from two different tribes, what are some of your favorite memories or family traditions?

From my direct family – my father and my mother – they started taking me to powwows at the age of one. We would travel up to Connecticut and as far as Oklahoma. Those are the memories I have, getting in the car with my parents and traveling to powwows. They wanted me to dance, be wrapped up in my culture – that was important to me. Traveling with my parents to powwows are definitely some of my main memories.

I gave dancing up for a while, but I got back into it when my father passed away. Right after my father passed away, I knew I needed to get back into my culture again. It had been instilled in me for so long. Why would I not use the talent that I had? I try to teach my six-year-old daughter and show her as much as I can, keeping her really wrapped up in our culture. We travel together and I take her to powwows.

You mentioned that you put a modern spin on your artwork. How do you tie your cultural heritage into your art while also making it modern?

The modern twist that I put to bonnets is on the headband part; all of the feathers are laid on the headband wrapped around, and stand up straight on a strip of leather. The spin I put on it was that I would trade cloth, and punch holes in it, and then weave the band together on a piece of rawhide. No one has actually seen the original bonnets, so we do not know how they were made. The Camden Historical Society doesn’t have any woodland bonnets at the moment.

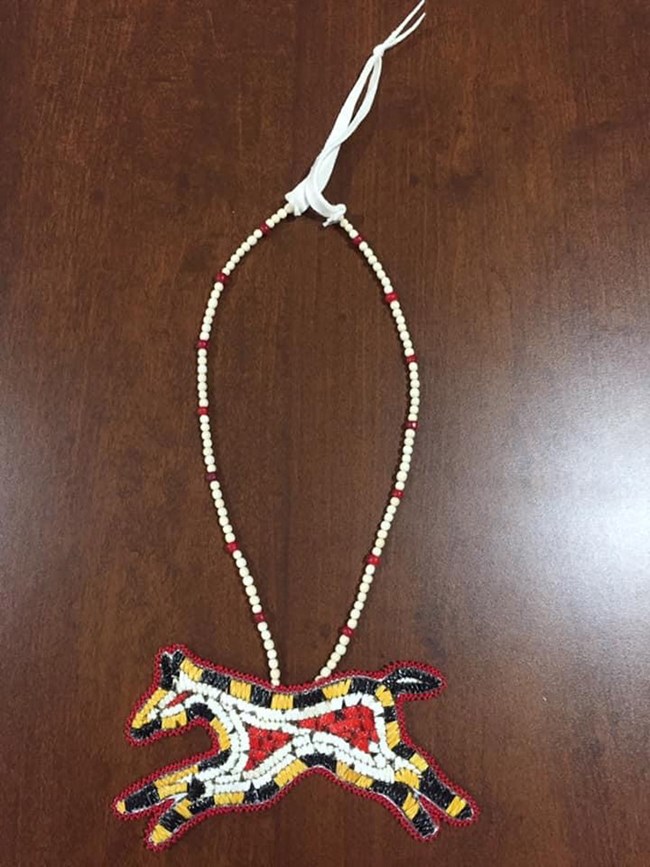

To make it look contemporary, I use bright colors and types of cloth and wool. For the pine needle wheels, synthetic sinew comes in all color variations. I figured out how to use all the synthetic sinew and all these colors to fade out colors into sunburst patterns. I fade yellow to red within the pine needle wheel with the sinew fabric. That is the modern spin I put to it. With the quillwork – for Woodland Natives, especially coastal Woodland Natives – wampum is a big deal. It is considered money. From what I was told, the Lenape were called the keepers of the white beads. The Haudenosaunee Confederacy (the Six Nations) were the keepers of the purple beads. I use a lot of wampum now within my quillwork, which you don’t really see a lot of people doing.

How can the public learn about your artwork?

I use Facebook and Instagram. Word of mouth and the social distance powwows have definitely given a big boost for me for the public to view my artwork.

During the pandemic, while social distancing, I go live on Facebook on a powwow page and do my quillwork live. I’ve had hundreds of thousands of people watching me at one time.

Leonard Harmon

Do you put any symbolism/imagery into your artwork?

Before I make a piece, I pray about it first. I am able to see what the piece looks like before I start working on it. It might be shown to me in a dream, but then it is for me to figure out how to do it on my own. I incorporate my own authenticity into my artwork.

What are some of your favorite pieces on display at museums?

The museum job I am doing for the Camden Historical Society is the biggest project and exhibition I’ve ever done. The exhibit is supposed to be open to the public in Summer 2021.

When people order art from me – unlike a museum display – I get to see people wearing my artwork when I go to powwows. When I travel to powwows all over the United States, there is somebody wearing something that I have made. That is better to me than having my art in a museum. I get to see my art danced in and worn– that is what means the most to me. Powwows are also open to the public, so anyone is welcome to attend as they wish!

Leonard Harmon

Do you celebrate any Native family traditions from both tribes?

Since colonialism, we have lost a lot of our ways. For the Nanticoke Tribe, the Piscataway is our sister tribe. We have lost all those traditions; it is sad. There is not any way that you can get that back. You can celebrate your tribe’s heritage and culture when you go to a powwow. Powwows are a western culture; they are not usually a Native Eastern tradition. Our tribe would have socials, which are a gathering of family.

My family in New Jersey, the Lenape, has a winter social annually. Our winter social is the closest thing we have to a celebration. It takes place on our tribal grounds and in a tribal center. This event is by invitation only, and just for family.

Tell us what is special about being from mixed indigenous heritage, as you are from both the Lenape Tribe and the Nanticoke Indian Tribe?

New Jersey, Delaware, and Maryland are all close together, so we are all kind of related and practice some of the same traditions.

If you go down to Millsboro, Delaware, a lot of people are mixed from different tribes, just like me. My last name, Harmon, is a prominent name in Millsboro. If you go to New Jersey, there are also people with the last name Harmon up there, too.

Leonard Harmon

What is the most rewarding part of being an intertribal citizen?

Family. Also, when I see people wear my art or clothing at powwows, that is also a rewarding feeling. When I sit there and look out at the circle and see someone wearing what I made, it brings back memories of when I was working on it. Seeing people proudly wearing my art means a lot to me. When my artwork is worn it gets to see the light of day – it gets to be danced.

How can the public support and learn more about the Lenape Tribe and the Nanticoke Indian Association?

Visiting the Nanticoke Indian Museum in Millsboro, Delaware is a big way to support us. Go to the Nanticoke Indian Tribe’s official website for more information. The Nanticoke Indian Museum has very old pieces of art and artifacts and I am proud to have some of my art displayed there. There is also a permanent exhibit on the third floor of the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, DC, with four items from the Nanticoke Tribe displayed in a glass case.

If you could create any exhibit to be put on display, what would it be?

My goal includes an idea that I have been working on for a while: I want to quill a rocking chair and have it displayed at the Heard Museum. I want to follow in the footsteps of my Uncle Lenny. The Heard Museum – that is when you reach the top – it can’t get any better than that. That means you’ve made it as an artist, and that is where I hope my work will be exhibited one day.

CARLY SNIFFEN

As an Interpretive Outreach Assistant, Carly hopes to share her passion for the environment with the community by working to develop and promote community engagement and working to restore and protect the Chesapeake Bay watershed.