Last updated: April 4, 2025

Article

League of the Physically Handicapped

The industrial revolution of the nineteenth century accelerated growth in urban communities turning many towns into cities. The increasing population of these newly crowded manufacturing centers brought illness, injury, and disability caused by large-scale industry. Partly in response to the growing visibility of impoverished people engaged in “street begging,” several cities in the United States instituted ordinances that forbade their appearance in public. These ordinances, which targeted the poor and effectively criminalized disability, eventually became known as “ugly laws.” Many of these laws were not repealed until the 1970s.1

As long as people have gathered in communities, people with disabilities have faced social exclusion and discrimination.2 Suppressed by laws and social attitudes that kept them isolated and hidden from sight, people with disabilities had few opportunities to organize and lobby for fair treatment. And yet, decades before the sit-ins and protests of the 1960s, Americans with disabilities pioneered some of the tactics that activists would employ during pivotal events of the Civil Rights Movement. Disabled WWI veterans, expecting rehabilitation in return for their service, planted the seeds of a disability rights movement.3 But government response and the resulting benefits accrued by these early efforts applied only to those who were disabled through military service. Disabled civilians remained unrecognized without many rights.

The 1960s is often understood as the beginning of the Disability Rights Movement. Disabled advocates rallied both locally and nationally demanding equal opportunities for employment and education. Their efforts, in part, are recognized in Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, which states:

no otherwise qualified handicapped individual in the United States shall solely on the basis of his handicap, be excluded from the participation, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving federal financial assistance.

The realization of law often takes time. When 504’s legal intent was interpreted inconsistently and its regulations remained unenforced, disability advocates such as Judith E. Heumann organized sit-ins in San Francisco and Washington, pressing the White House to enforce 504 provisions. Their efforts to raise awareness established the basis for the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), the first concrete federal civil rights protection for people with disabilities.4 Both the ADA and the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 were based on the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

While the magnitude for the achievements of American disability advocates in the 1960s and 70s cannot be overstated, this was not the first time a group of disability advocates organized, gathered, and protested for their civil rights using similar tactics.

Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Library of Congress.

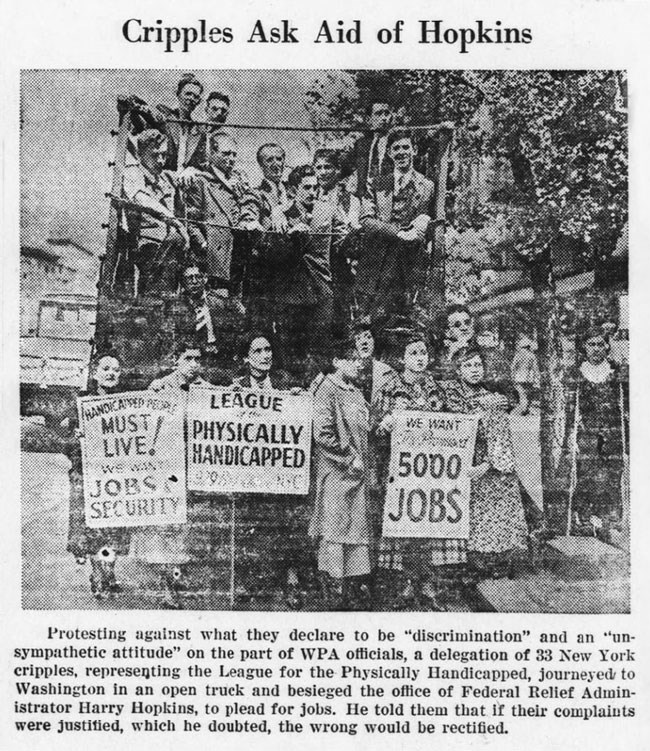

This is a black and white image of a news clipping.

Image Title: Cripples Ask Aid of Hopkins

Image Description: Nineteen people standing in and around an open air truck. Some people are smiling. Some people are serious. One woman is standing with crutches. The people in front are holding three protest signs. The sign on the left reads "Handicapped People Must Live. We Want Jobs & Security." The sign in the middle reads "League of the Physically Handicapped" (bottom line unclear). The sign on the right reads "We Want The Promise of 5000 Jobs."

Image Caption: Protesting against what they declare to be "discrimination" and an "unsympathetic attitude" on the part of WPA officials, a delegation of 33 New York cripples, representing the League for the Physically Handicapped, journeyed to Washington in an open truck and besieged the office of Federal Relief Administrator Harry Hopkins, to plead for jobs. He told them that if their complaints were justified, which he doubted, the wrong would be rectified.

Chartered in 1942, the American Federation for the Physically Handicapped was the first national disability non-profit to lobby against job discrimination.5 However, seven years earlier, a group of physically disabled New Yorkers employed “militant and aggressive” demonstration tactics to protest certain policies of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration (WPA).6 They called themselves the League of the Physically Handicapped.

In 1935, a “formal but secret” WPA policy classified disabled people as “unemployables.”7 The League was not the only organization drawing attention to this policy. In a letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt dated April 19, 1935, H. D. Hicker and M. M. Walter, President and Chairman respectively, of the National Rehabilitation Association wrote:

An essential factor in the success of this program will be the attitude toward the disabled of those who are responsible in the States for the administration of the Works Program and the Emergency Relief activities. It has already come to our attention that discrimination has been shown against the employment of the disabled in these activities, on the basis that they are unemployable. Fourteen years of experience in rehabilitating the disabled, during which time over 70,000 persons have been rehabilitated, proves that workers, though partially disabled, are not unemployable. In the establishment of the Codes under the N.R.A., due to your order covering the physically disabled, discrimination against them by private employers has been prevented. May we, therefore, appeal to you . . . that in the development of the Works Program no arbitrary decision be made classifying all handicapped persons as unemployable?8

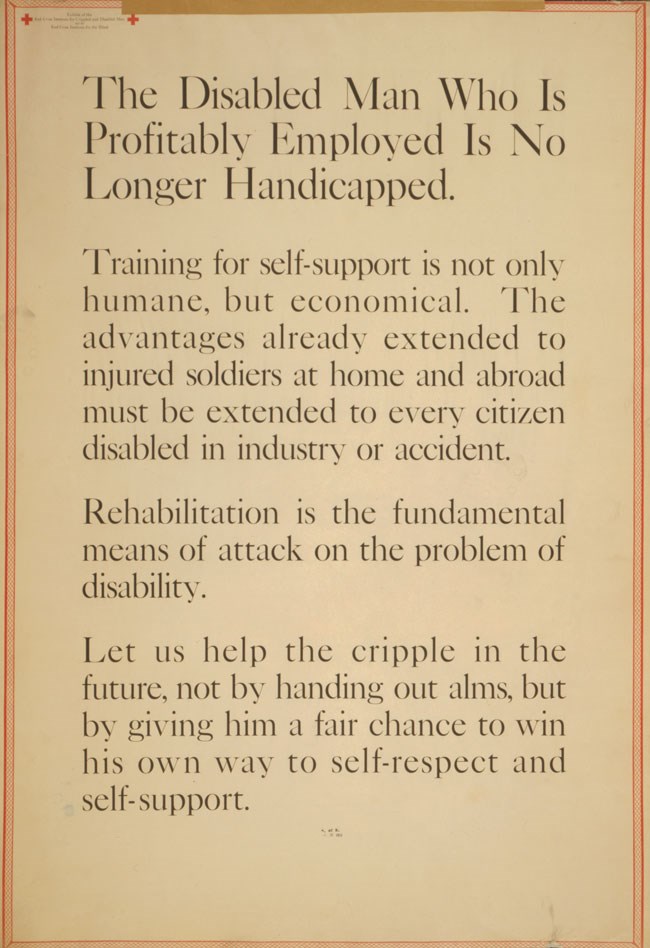

Hicker and Walter received a response from Louis Howe, Secretary to the President, assuring them that Harry Hopkins, Director of the Federal Emergency Relief Agency, is “at the present time giving service to large numbers . . . of disabled persons in rehabilitating them for future employment. It is the President’s desire that this shall continue under the new work program and that as large a number as possible of these persons shall be aided.”9 Despite the fact that not all disabled people could be rehabilitated, during the years that followed World War I, there was an emphasis on rehabilitation as the only solution for achieving employment.

However, rehabilitation of disabled individuals often did not result in employment at federal and state expense. Dr. R. M. Little, Director of the Rehabilitation Division of the New York State Education Department, wrote in October 1935, “I wish [FDR] to know that the administrator of the W.P.A. in upstate New York has taken a narrow and unjustifiable position” in declining “to give consideration to the employment of properly trained physically handicapped clients of this Division.”10

Ironically, the New Deal did have disabled leadership. Head of the WPA Writers Project Orrick Johns used a wooden leg, and WPA administrator for New York City Victor Ridder is said to have used a “built up shoe.”11 Furthermore, President Roosevelt’s own Executive Order (No. 7046) Prescribing Rules and Regulations Relating to Wages, Hours of Work, and Conditions of Employment Under the Emergency Relief Appropriation Act of 1935, stipulated that the WPA should not discriminate against the employment of disabled people:

No person under the age of sixteen (16) years, and no one whose age or physical conditions is such as to make his employment dangerous to his health or safety, or to the health and safety of others may be employed on any work project. This paragraph shall not be construed to operate against the employment of physically handicapped persons, otherwise employable, where such persons may be safely assigned to work which they can ably perform [emphasis added].12

Despite Roosevelt’s intent, the League claimed that WPA programs excluded disabled people from work relief and compensation opportunities based on discrimination. The League, and others, would use FDR’s executive order to challenge the implementation of the WPA’s policies. In the above-referenced letter from the Director of the Rehabilitation Division of the New York State Education Department, Dr. Little observed, “We called attention to the fact that you [FDR] had requested that physically handicapped persons be given consideration upon their merits,” and that disqualifying disabled people as unemployable was “so contrary to the public utterances of the President, and what I feel sure are his wishes.”13

Library of Congress

Memorandum is addressed to Colonel W. T. Sexton for transmission to Colonel Frank McCarthy.

The message in this memorandum is typed in all caps.

Spaman to Reilly. (Spaman and Reilly are crossed out and annotated in ink as Bacon to Aspen). Complete list of Spruce party follows: Beech Cedar Walnut Willow Chestnut Pine Hemlock Bacon Cabby Fagot Behn Deckard Haman Shannon Spicer (a word crossed out with exes). George Fox/Prettyman and Warrant Officer Cornelius Army. Walnut advises following will accompany us only to point where we leave Holly Esperancilla Orig Abiba Floresca Calinao Enrico Estrada and Ordona. Three fifty fours including one all fixed up will leave tenth with two Dayton Articles (the word ramp crossed out with exes) for same and I will take third Dayton (the word ramp crossed out with exes) with me. These will arrive regal thirteenth and fourteenth. Colonel Stalter who understands Dayton (the word ramps crossed out with exes) set up will arrive with first fifty four and Dayton (the word ramp crossed out with exes) and your General Melot (crossed out and annotated in pencil with Emloy) will be in contact with Stalter on arrival regal for further instructions from you. Eighty seven A will leave eleventh with small Daytons (the word ramps crossed out with exes) and arrive regal fifteenth but Willow (a word crossed out with exes) says they prefer same set up as before. I expect to leave eleventh.

Disability has long been a central issue of U.S. labor, class, and immigration history, yet its importance has often been ignored by historians. Rather than understanding disability as a social construction or source of shared identity, it is more commonly understood as an individual medical problem.14 This medical model ideology has not only caused historians to discount how disability shapes social and political life, but it has also made it difficult for disabled activists to organize under a shared identity. The League of the Physically Handicapped not only challenged public policies related to disability, they also challenged such misunderstandings of disability. They argued that their visible impairments, many of which were caused by poliomyelitis, led to shared experiences of discrimination. By contrast, the social model ideology recognizes that discrimination effectively “disables” an individual’s place in society, including their access to employment. Disabled people at this time, the League argued, faced discriminatory categorization as beggars, villains, sinners, unworthy citizens, children, and victims forced to receive charity relief rather than fair employment.15 This combination of informal social discrimination and formal statutory law exclusion resulted in the classification of thousands of disabled people as unemployable under the Works Progress Administration in 1935.

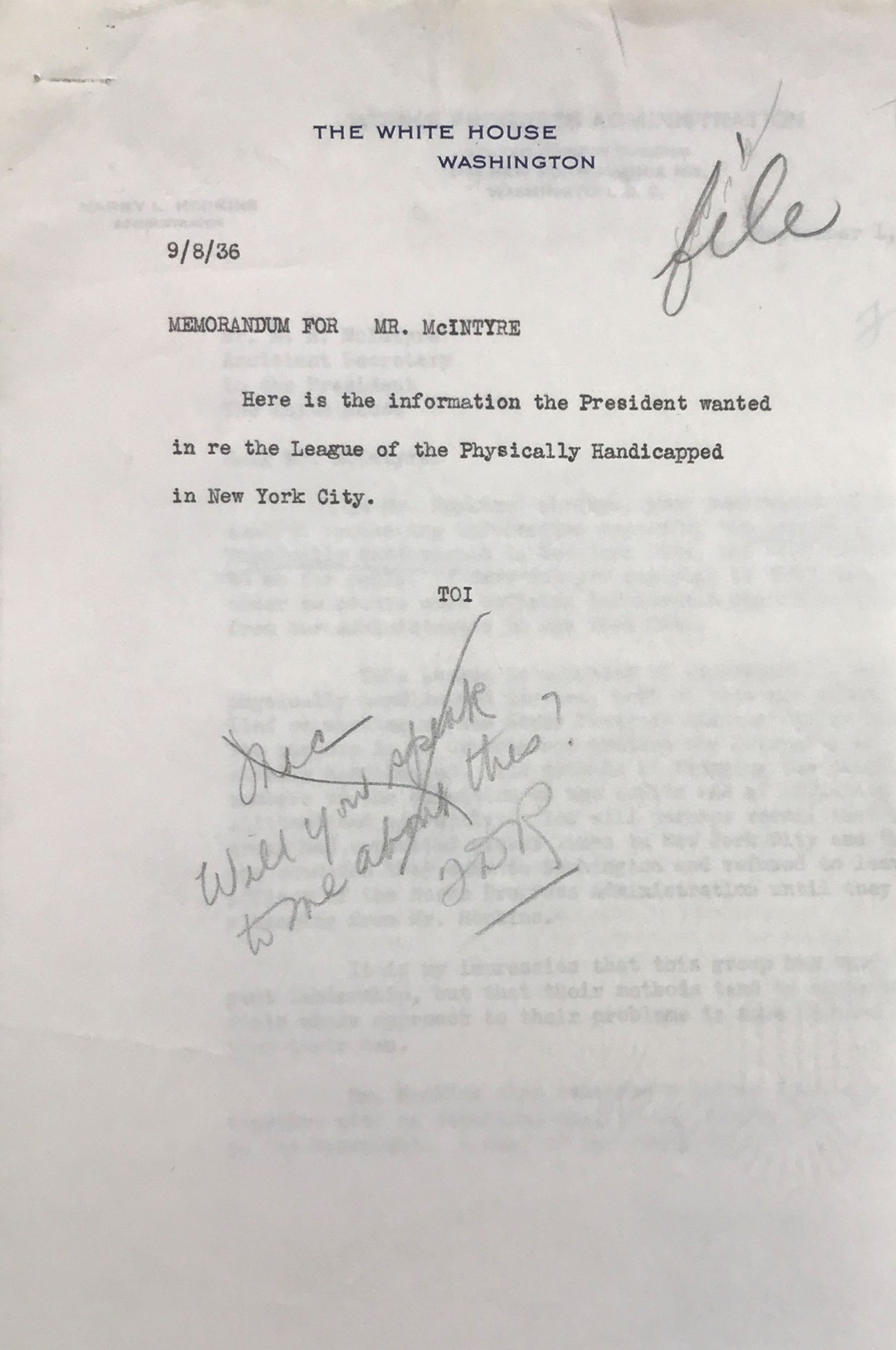

Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library.

Despite his own polio-related paralysis, FDR did not seem to share the political ideology of the League. In contrast to common discriminatory categorizations, FDR emerged as a symbol of rehabilitation who overcame personal adversity.16 This socially acceptable image allowed him some exemption from the prejudice faced by other disabled people, many of whom did not have access to the wealth and privilege that enabled FDR to pursue rehabilitation and physical access. This image was strategically crafted to portray FDR as a viable and strong political candidate in a culture that viewed disability as weakness.17 Under attack by political opponents during his gubernatorial campaign for Governor of New York, FDR had to speak openly for the first time about disability, submitting his physical condition to public review.

While it is true that a public image emerged to represent FDR as an individual who overcame paralysis (as many others did), his association with founding and developing the Georgia Warm Springs Foundation and his surviving correspondence over certain disabled persons add nuance to Roosevelt’s disability legacy. FDR first visited Warm Spring in 1924 seeking a cure for his paralysis. Encouraged by results of swimming in the therapeutic waters at Warm Springs, Roosevelt purchased the failing resort of 1,200 acres in 1926, eventually investing over two-thirds of his personal assets to establish a research and rehabilitation institute for the treatment of infantile paralysis.

In 1931 patients who received treatment at Warm Springs formed the National Patients Committee, a group of disabled activists who not only advocated for treatment and a cure but also to end social discrimination of disabled people and make public buildings more accessible.18 Warm Springs was recognized as an exemplar accessible world where physically disabled people could move around as freely as the able-bodied. Within a few months of their formation, the Committee published the first issue of the Polio Chronicle, a newsletter made by and for people affected by polio. In a 1934 issue, one author stated, “The paral, like anyone else, should feel that all people and places, thought and actions, arts and science, are open to him. Physical handicap should raise no barrier against him.”19 By 1935, the Warm Springs Foundation broadened its mission to promote the employability of disabled people.20

While hundreds of letters from the disabled and their advocates to President Roosevelt attest to his significance as an inspirational figure, not all disabled people viewed FDR as a role model who overcame disability and its stigma. This was true for the League, who did not embrace FDR as an inspiration, and even rejected this identity for themselves. They challenged WPA policies denying their access to federal work relief. Describing their technique as “militant and aggressive” (and subsequently confirmed by the President’s advisors), the League protested in New York City and Washington D.C. demanding that Emergency Relief Bureaus and the President’s administration establish nationwide quotas for disabled workers in relief jobs. While FDR was seen by many as a friend of the American worker, the League’s public demonstrations painted a different picture—disabled job seekers were irrelevant within the WPA despite the President’s express wish to protect their rights to employment.

There were other instances in which FDR advocated for the employment of disabled workers who wrote to him, despite receiving hundreds of requests. In 1935, William J. Maund, Jr. of Philadelphia wrote Eleanor Roosevelt documenting problems he experienced seeking employment. His application for a position in the Federal Farm Administration was rejected by the Civil Service Commission “because of his physical condition.” Word reached FDR, who informed his Assistant Secretary Marvin McIntyre, “that he desires to speak to the Chairman of the Civil Service Commission about this matter.”21 This was not the only time FDR personally intervened for disabled people facing discrimination. George Marvin wrote the President in May of 1935 on behalf of “a victim of infantile paralysis . . . who is in desperate need of a job.” Responding for FDR, Grace Tully (his secretary) encouraged Mr. Marvin to help his friend find a job with the assurance that “the President has been trying to get all employers of fifty people or more to take on at least one handicapped or crippled person who is not on the relief rolls.”22

Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Library of Congress.

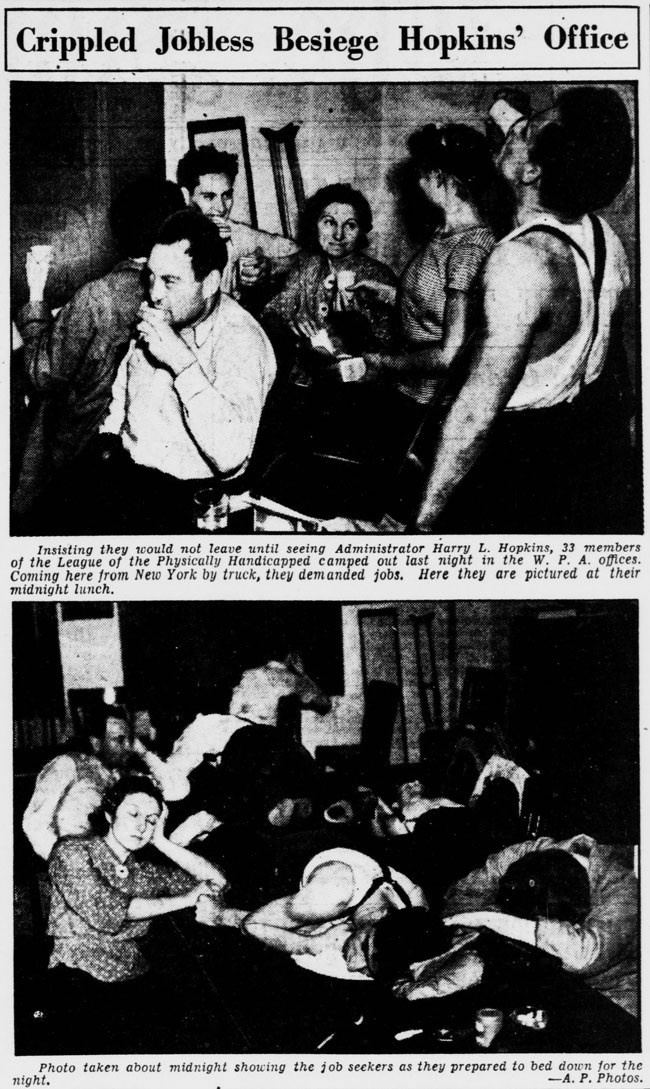

This is a black and white image of a news clipping with two photos.

Image Title: Crippled Jobless Besiege Hopkins' Office.

Top Image Description: Six people gathered in a room drinking from paper cups and eating sandwiches. A crutch leans against a wall behind the group.

Top Image Caption: Insisting they would not leave until seeing Administrator Harry L. Hopkins, 33 members of the League of the Physically Handicapped camped out last night in the W. P. A. offices. Coming here from New York by truck, the demanded jobs. Here they are pictured at their midnight lunch.

Bottom Image Description: Seven people around a table. Some are resting eyes closed with their head resting in their hands, others are resting their head on the table.

Bottom Image Caption: Photo taken about midnight showing the job seekers as they prepared to bed down for the night.

In the spring of 1936, after many months of protests and no response from WPA leadership, the League camped out at the office of Harry Hopkins. Hopkins finally agreed to meet with League delegates. The League demanded five thousand WPA jobs for disabled workers, a permanent relief program, and a nation-wide census of the physically disabled. Hopkins doubted that five thousand employable disabled people existed in New York alone, and he therefore asked the League to conduct the census themselves. The League did, and they delivered the results not only with Hopkins, but to FDR’s administration and the press.

The results of the census were reported in the “Thesis on Conditions of Physically Handicapped.” It described unjust exclusions of physically disabled people in private sector jobs, insufficient state-sponsored vocational rehabilitation efforts, and the exploitation of disabled people in sheltered workshops that were exempt from minimum wage requirements. The report illustrated the importance of self-advocacy in a time when nondisabled policy makers were complicit in its findings. The report highlighted FDR’s prohibition of discriminatory practices in Executive Order 7046 as confirmation of the WPA’s responsibility to offer work relief for disabled people.

FDR’s influence in this matter is unclear, but the surviving documentation indicates he was aware of their demands and asked for more information. The memorandum demonstrates a rare example of his personal interest amongst hundreds of similar requests for the president’s attention. We have no evidence of the discussion that took place between Roosevelt and McIntyre. While the League’s report did sway WPA officials and resulted in job offers to disabled people in some places, it was much less than the League demanded.23

Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library

The League of the Physically Handicapped was the first direct-action disability activist group in the United States.24 While the League criticized the Roosevelt administration, language in Executive Order No. 7046 to discourage discrimination of the physically handicapped in federal employment was echoed in Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and other landmark disability civil rights legislation.

Rather than attempting to radically change how society understands disability and disabled people, the League of the Physically Handicapped followed the path of other civil rights movements by focusing on personal goals. These included attempts to shift the social role of disabled people to one that is “normal” and to find jobs for individuals. Many disability scholars today no longer adopt this perspective and argue these goals hinder community building by favoring individualism and strengthening exclusionary boundaries of who can be considered “normal.” However, in their brief history of activism, the League represented the importance of disability advocacy and political solidarity at a time when even our highest government officials primarily considered disability to be a personal rather than political problem.

Shelby Landmark, PhD and Frank Futral

Shelby is the Mellon Fellow for Disability Representation at Historic Sites at the Home of Franklin D. Roosevelt National Historic Site.

Notes

Much of the League's history outlined in this article is from Paul K. Longmore, "The League of the Physically Handicapped and the Great Depression: A Case Study in the New Disability History," The Journal of American History, vol. 87, no. 3 (Dec. 2000).

1 Schweik, S. M. (2009). The Ugly Laws: Disability in Public. NYU Press.

2 Gershon, L. (2020). The rise of disability stigma. Daily JSTOR. The Rise of Disability Stigma - JSTOR Daily

3 Maloney, W. (2017). World War I: Injured veterans and the disability rights movement. Library of Congress Blogs. World War I: Injured Veterans and the Disability Rights Movement | Timeless (loc.gov)

4 Cone, K. (1997). Short history of the 504 sit-in. Disability Rights Education & Defense Fund. Short History of the 504 Sit in (dredf.org)

5 The AFPH described themselves as “an organization of handicapped persons and their friends devoted to a program and policy which would enable the handicapped to assume their rightful place as self-sustaining citizens.” From AFPH’s 1955-1956 Legislative Program, 1955-1956 Legislative Program, American Federation of the Physically Handicapped, Inc. | Texas Disability History Collection (uta.edu)

6 In a letter to Marvin H. McIntyre, the Assistant Secretary to President Roosevelt, Aubrey Williams, the Deputy Administrator of the Works Progress Administration, said the League’s “methods of bringing the plight of its members to the attention of the public and of officials are militant and aggressive.” Williams, A. (1936, September 1). Letter to Mr. M. H. McIntyre. Official File 836, Box 1, Physically Handicapped Persons 1936.

7 Our History: League of the Physically Handicapped flier, circa 1935, Our History (nyc.gov).

8 Hicker, H. D., & Walter, M. M. (1935 April 19). Letter to Franklin D. Roosevelt. Official File 836, Box 1, Physically Handicapped Persons 1935, FDRL. The National Rehabilitation Association was created in the 1920s out of the need to provide social and professional services to those in need of rehabilitation.

9 Howe, L. (1935 May 2). Letter to National Rehabilitation Association. Official File 836, Box 1, Physically Handicapped Persons 1935, FDRL.

10 Little, R. M. (1935 October 30). Letter to Franklin D. Roosevelt. Official File 836, Box 1, Physically Handicapped Persons 1935, FDRL.

11 Johns, O. (1937). Time of Our Lives: The Story of My Father and Myself. Stackpole.; Brown, B. (1935). March of the Cripples, 17(9). New Masses. ‘March of the Cripples’ by Bob Brown from New Masses. Vol. 17 No. 9. November 26, 1935. – Revolution's Newsstand (revolutionsnewsstand.com).

12 Executive Orders and Presidential Proclamations, 1933-1936, Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum; eo0029.pdf (marist.edu).

13 Little, R. M. (1935 October 20). Letter to Franklin D. Roosevelt. Official File 836, Box 1, Physically Handicapped Persons 1935, FDRL.

14 Olkin, R. (2022). Conceptualizing disability: Three models of disability. American Psychological Association. Conceptualizing disability: Three models of disability (apa.org).

15 Fleischer, D., & Zames, F. (2001). The Disability Rights Movement: From Charity to Confrontation. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

16 For a genealogy of this type of “narrative of overcoming,” see: DeVolder, B. (2013). “Overcoming the overcoming story: A case of ‘compulsory heroism.’” Feminist Media Studies, 13(4), 746-754.

17 Like all politicians, FDR’s public image was carefully managed. Our research continues to clarify to what extent FDR himself and/or his advisors took in strategically representing his disability. For a deeper discussion on the possible rhetorical strategies of FDR’s public image, see Houck, D. W., & Kiewe, A. (2003). FDR’s body politics: The rhetoric of disability. Texas A&M University Press.

18 Rogers, N. (2009). Polio Chronicles: Warm Springs and disability politics in the 1930s. Asclepio; archivo iberoamericano de historia de la medicina y antropologia medica, 61(1), 143–174. https://doi.org/10.3989/asclepio.2009.v61.i1.275

19 Anon. (1934, February). Accessibility, Polio Chronicle. Copy in NPS files.

20 (1935), Arthur Carpenter to the Editor, JAMA, 105, p. 1932

21 McIntyre, M. H. (1935 January 10). Personal communication about letter from William J. Maund, Jr. to Eleanor Roosevelt. Official File 836, Box 1, Physically Handicapped Persons 1935, FDRL.

22 Tully, G. (1935 May 27). Personal communication about letter from George Marvin to Franklin D. Roosevelt. Official File 836, Box 1, Physically Handicapped Persons 1935, FDRL.

23 Memorandum for Mr. McIntyre, September 8, 1936, Official File 836, Box 1, Physically Handicapped Persons 1936.

24 Shaw, W. (2021). Disability History NYC, The League of the Physically Handicapped. Disability History NYC — disabilityhistoryNYC.com

Tags

- home of franklin d roosevelt national historic site

- disability history

- disability history disability rights movement

- disability history empowerment and community

- franklin d roosevelt

- labor history

- new deal

- wpa

- federal emergency relief agency

- fdr

- presidents

- disability awareness

- disability

- disability activism

- disability history early attitudes

- mellon humanities fellowship

- civil rights