Last updated: June 30, 2024

Article

Ladd and Whitney Monument

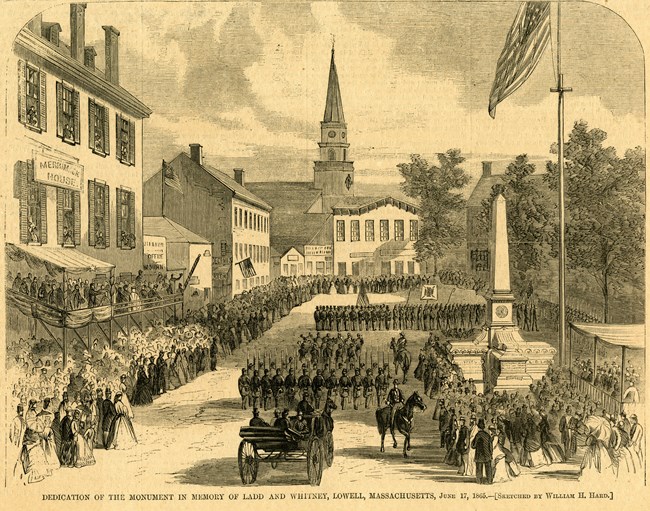

On June 17th, 1865, the citizens of Lowell gathered around Merrimack Square to dedicate a monument to Luther C. Ladd and Addison O. Whitney. Ladd and Whitney might never have been remembered in history, but for the fact that they shared the distinction of being among the first soldiers to die in the American Civil War.

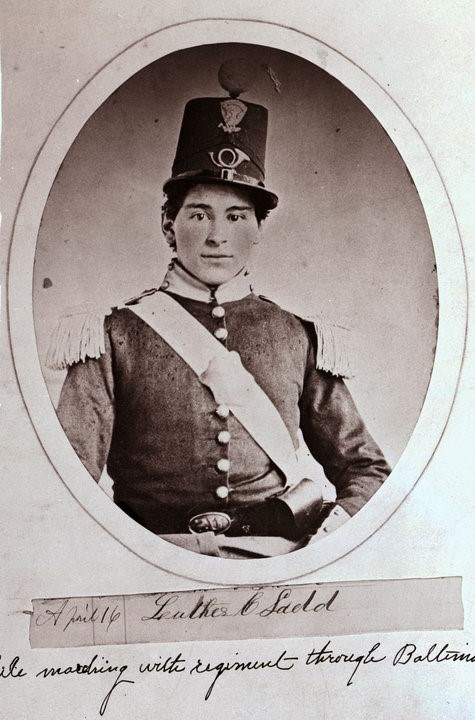

Lowell Historical Society

Luther C. Ladd was born in Alexandria, New Hampshire on December 22nd, 1843. In the spring of 1860, he joined his three sisters in Lowell and began work at the Lowell Machine Shop. He resided in the city only a year when he responded to the call of President Lincoln for 75,000 volunteers and joined a regiment which had already been organized in the apprehension of a civil war.

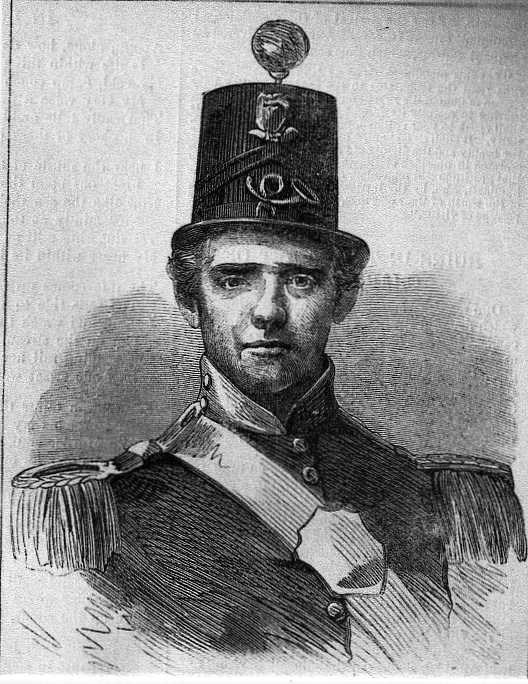

Harper's Weekly Magazine

Addison O. Whitney was born in Waldo, Maine on October 30th, 1839, although other sources claim 1836. He arrived in Lowell in 1859 and was employed in the no. 3 spinning room of the Middlesex Mills. He had formerly been in the Lowell City Guards, Lowell’s local militia, but had left to learn a trade. Upon hearing the call for volunteers, he rejoined, and became part of the Lowell company in which Ladd also served. On the evening of April 15th, 1861, both received word that in the morning, they must depart for the war. Early on the 16th, before leaving Lowell, both Ladd and Whitney stopped to have their portraits taken.

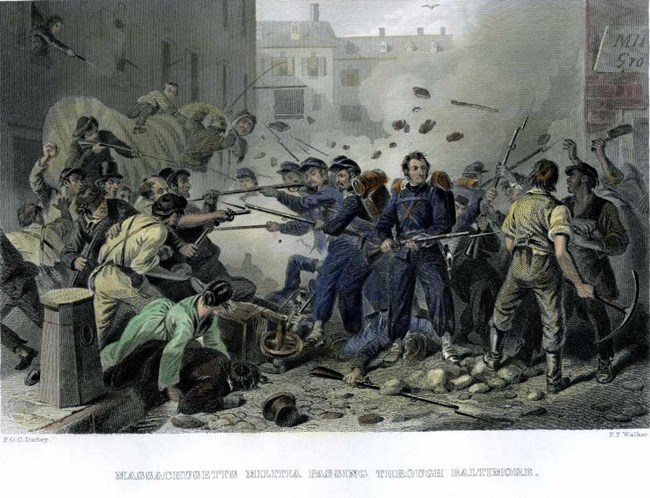

F. F. Walker and F. O. C. Darley, Library of Congress or Library of America

As members of Company “D” of the 6th Massachusetts Regiment, Ladd and Whitney were part of the first regiment in the country to be organized and sent southward to defend Washington, D.C. Both were present while the regiment marched through Baltimore on April 19th, 1861. A crowd of southern sympathizers mobbed the Lowell company in which Ladd and Whitney had enlisted. Members of the mob attacked the 6th with stones, bricks, clubs, and firearms. After several of their members fell, the 6th returned fire. 40 members of the 6th Massachusetts became casualties that day, 36 wounded and four killed, the first of whom was Luther C. Ladd, with Whitney falling afterward. As Ladd fell, he was reported to have exclaimed with his dying breath: “All hail to the stars and stripes!” Who heard him say this is never mentioned, and the story is likely apocryphal. When Ladd's body was recovered, he had suffered a fractured skull and a bullet which severed an artery in his leg. Veterans of the 6th Massachusetts would claim that a man named Wrench, of Williamsport, Maryland, was Ladd’s killer. They were said to have heard of him boast of killing the “boy soldier who shouted for the stars and stripes as he fell.” Without further evidence, this story, too, seems apocryphal.

Also among the dead of the 6th Massachusetts were Sumner H. Needham of Lawrence, Massachusetts, and Charles A. Taylor. Charles Taylor had joined the regiment in Boston and was not personally known to any of the members before then. He was not uniformed at the time and was only recognized as a soldier when members of the 6th came to identify his body. A fifth member, John Ames, is sometimes added to the list of the killed. However, he was not listed on the original list of the dead from that day, but rather appears on the list of the wounded. Between nine and 12 residents of Baltimore were also killed, and an unknown number were wounded.

Ladd and Whitney's bodies were recovered, and sent to Lowell. Funeral celebrations were held in Huntington Hall, above the Boston and Lowell Railroad Depot, which reportedly drew the largest crowd ever assembled for a public funeral in the city. There was a large procession as the coffins were conveyed to the Lowell Cemetery. Before interment, Ladd’s body was sent to his hometown of Alexandria for additional funeral ceremonies attended by his parents, John and Fanny Ladd, and then returned to Lowell. Whitney’s father, John Whitney, consented to have his son’s body remain in Lowell. Whitney’s mother Jane’s thoughts on the matter are not recorded. Needham’s body was returned to Lawrence, and a similar grand ceremony held there. A monument was constructed to him in the Lawrence Cemetery. He left behind a wife and child, unnamed in the historical record. Taylor’s friends, relatives, and hometown were searched for, but in vain. With no one to claim his body, Charles Taylor was buried in Baltimore.

Ladd and Whitney remained interred in the Lowell Cemetery for several years, but as early as 1863, Lowell planned to construct a monument to the "first martyrs of the great rebellion". The State of Massachusetts provided $2,000 for the project, and resident of Lowell raised an additional $2,000. The monument was placed in April of 1865, with ceremonies originally slated for the 19th of that month. This was both the anniversary of the Baltimore Riot, and the Battles of Lexington and Concord in Massachusetts in 1775. Citizens of the state felt this imbued the date of Ladd and Whitney’s deaths with additional significance. The dedication was delayed due to the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, and a second date of significance in Massachusetts' history chosen: the anniversary of the Battle of Bunker Hill.

Sketched by William H. Hard; Harper’s Weekly, July 8, 1865

Thus, on June 17th, 1865, the crowd gathered around Merrimack Square, thereafter known as Monument Square, to attend the ceremony honoring the two soldiers. Later, Charles Taylor’s name would be added to the monument, in remembrance of the fourth and almost unknown man of the dead of the 6th Massachusetts. Among the speakers that day was then governor of Massachusetts, John A. Andrew, who charged the citizens of Lowell with keeping and preserving the monument, and with it the memory of Luther C. Ladd, Addison O. Whitney, and the hundreds of thousands of soldiers who had died to end slavery and restore the Union. The bodies of Ladd and Whitney were disinterred from their graves and were reinterred beneath the monument where they rest to this day.