Last updated: December 19, 2023

Article

Shrinking Glaciers in Katmai National Park and Preserve

Alaska is one of the most heavily glaciated areas in the world outside of the polar regions. Approximately 21,835 square miles of the state are covered in glaciers—an area nearly the size of West Virginia. Glaciers have shaped much of Alaska’s landscape and continue to influence its lands, waters, and ecosystems. Because of their importance, National Park Service scientists and partners measure glacier change. They have found that glaciers are shrinking in area and volume over nearly all the state. From 1985 to 2020, glacier-covered area in Alaska decreased by 13%. Over the same period, Katmai National Park and Preserve experienced a 16.5% reduction in glacier-covered area. As our climate continues to warm, these changes will continue to occur and likely accelerate, profoundly impacting the landscape of Alaska and our parks for generations to come.

Glaciers in Katmai

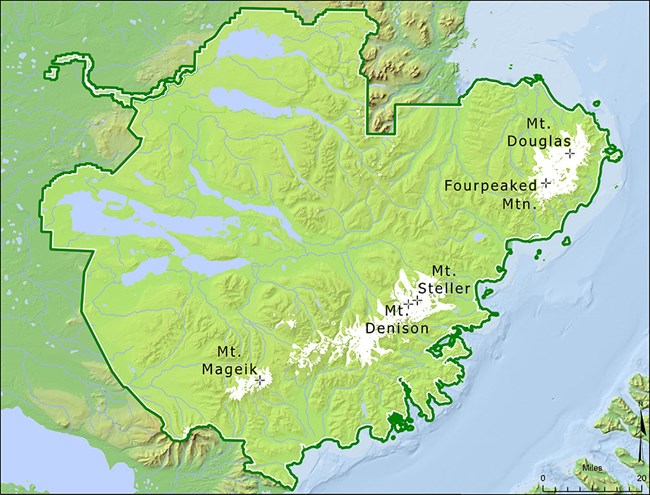

Katmai National Park and Preserve is one of nine national parks in Alaska with glaciers. Katmai is on the northern Alaska Peninsula, situated between the shallow, seasonally ice-covered Bristol Bay and the warmer, deep waters of the

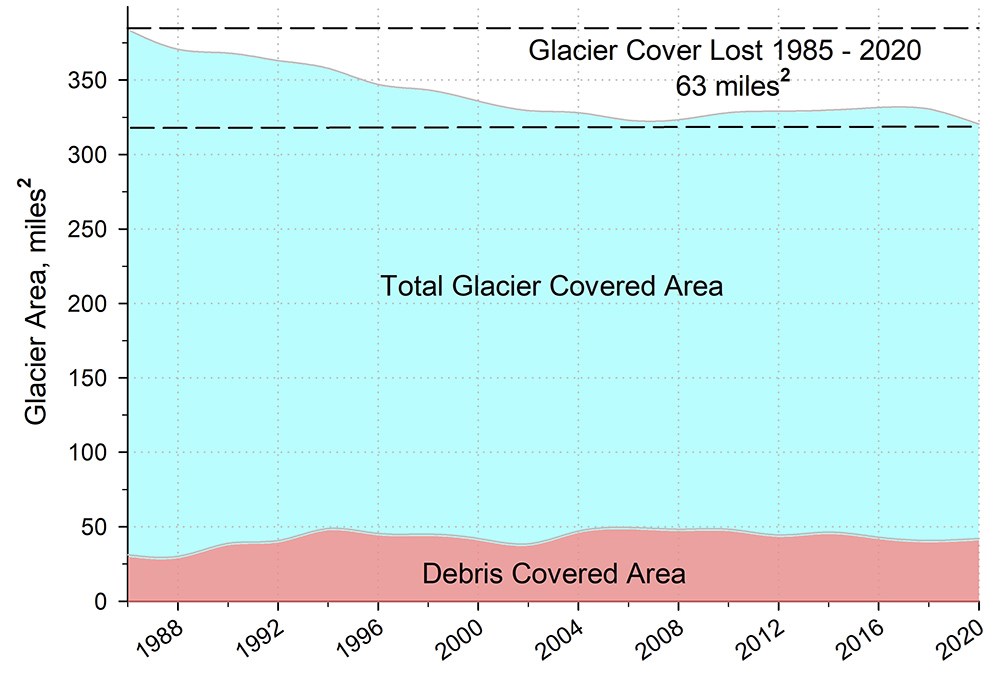

northwestern Gulf of Alaska. Glaciers covered 320 square miles (829 km2) of Katmai in 2020 (Figure 1). This number is 16.5% less than in 1985, meaning that Katmai lost about 63 square miles (164 km2) of glacier-covered area over the 35-

year period. Glacier cover in Katmai decreased by 14% from the 1950s to the early 2000s.

Katmai’s volcanic peaks are part of the “Ring of Fire,” known for its earthquakes and volcanic activity, and all of Katmai’s glaciers are on or near an active volcano. A central feature of Katmai is the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes, an area formed by the massive 1912 eruption of Novarupta Volcano. Deep deposits of ash from the 1912 eruption are frequently lifted and scattered by the region’s strong winds, such that ash covers many of the glaciers nearby. In some cases, thin layers of ash (less than an inch thick) speed the melting process of new, clean snow or glacier ice by making it darker and more absorbent of the sun’s radiation. In other cases, however, the ash is thick enough that it insulates the ice and slows the melting process.

R.G. McGimsey, Alaska Volcano Observatory/U.S. Geological Survey

The Knife Creek Glaciers (Figure 2), which flow from the top of Katmai Volcano, are examples of glaciers that have changed little over time due to their thick layer of insulating ash. When nearby Novarupta erupted it affected the magma underlying Katmai Volcano, which led to the draining of Katmai’s magma chamber and a drop in its summit, effectively “beheading” the high-elevation accumulation zones of the glaciers. Although these glaciers have changed little, overall glacier cover in the park since 1985 has decreased (Figure 3), as it did from the 1950s to the early 2000s.

Statewide Glacier Change

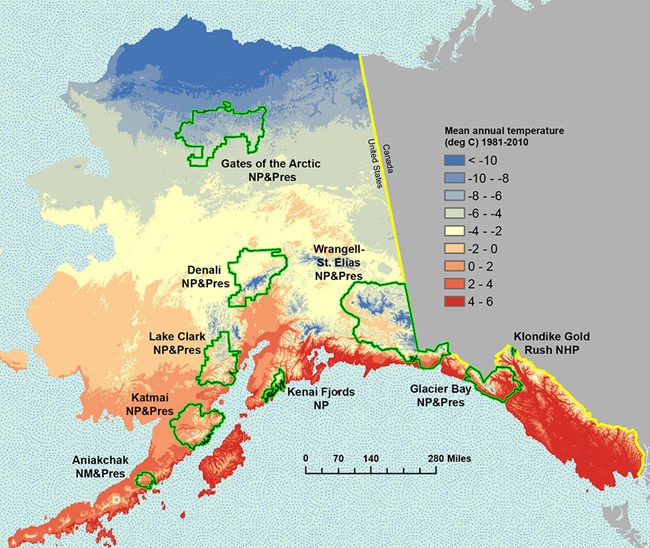

Alaska’s high-latitude and high-elevation mountain ranges have historically had average annual temperatures cold enough to sustain glaciers. However, global air temperatures are increasing, and Alaska and other high-latitude regions are warming faster than the average global rate. Data from NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information indicate Alaska’s statewide average annual temperature has been increasing by 0.6°F per decade since 1950. As temperatures warm, the elevation at which snow and ice remain frozen is getting higher, with more rain and less snow at lower elevations. The effects are most visible at a glacier’s lowest elevations, where most glacier termini are rapidly retreating.

From 1985 to 2020, glacier-covered area in Alaska decreased by 13%, or 3,253 square miles (8,425 km2). Glaciers within national parks in the state (parks shown in Figure 4, along with average annual temperatures) decreased by 8% from the 1950s to the early 2000s. From 1985 to 2020, the largest changes in glacier-covered area in Alaska occurred at elevations of 2,625–7,218 feet (800–2,200 m) and in southern Alaska—the region that encompasses the greatest glacier-covered area. Little change was seen in the relatively small glaciers of the Brooks Range in northern Alaska.

Because of the importance of Alaska’s glaciers and the implications of glacier loss, including for how we manage parks, glacier monitoring and assessment will continue to be a critical, ongoing activity of the NPS and its partners.