Last updated: February 25, 2021

Article

Juneteenth in Gettysburg

On June 19, 1865, Major General Gordon Granger entered Galveston, Texas, with critical news: the American Civil War was over, and enslaved African Americans were free. To commemorate the occasion, black Texans held the first Juneteenth celebrations.

Although Juneteenth has become prominent, African Americans celebrated numerous “Emancipation Days” after the Civil War. Black residents in Richmond, Virginia, commemorated April 3rd, the day Richmond fell to Union troops, while others chose dates marking the passage of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments. The variety of anniversaries underscored the gradual process by which African Americans attained freedom from chattel slavery. Slavery had not disappeared on January 1, 1863, when President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. As Juneteenth illustrates, it remained intact for many African Americans until 1865.

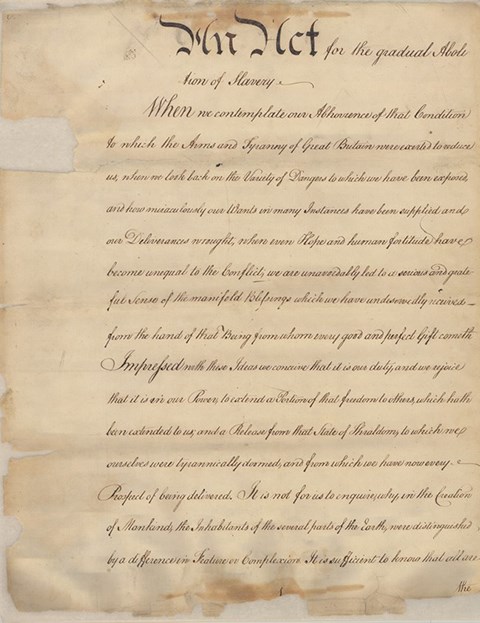

Emancipation had been gradual for black Pennsylvanians, too. In 1780, the state of Pennsylvania passed “An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery.” The act did not free a single slave in Pennsylvania, but it stipulated “that every Negroe [sic] and Mulatto Child born within this State after the passing of this Act as aforesaid” would become free after twenty-eight years of servitude. Between 1799 and 1820, a Gettysburg register documented the births of 109 black children.

Adams County Historical Society

Slavery maintained a presence in Gettysburg after the last enslaved Pennsylvanian gained their freedom in 1847. Slave hunters from Maryland and Virginia frequently crossed the border in pursuit of freedom seekers. African Americans operating the Underground Railroad in Gettysburg had to be vigilant: slave hunters kidnapped fleeing African Americans and free people of color. In 1858, a group of slavers attacked Mag Palm, a member of Gettysburg’s Underground Railroad. Palm used her physical strength to thwart her assailants, and supposedly bit off someone’s thumb, but she was not yet safe. As long as slavery existed, free people of color were tenuously “free” at best. They had to wait together—in Richmond, Galveston, and Gettysburg—for slavery’s true demise.