Part of a series of articles titled French Language and the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

Article

Joseph Gravelines and the Lewis and Clark Expedition

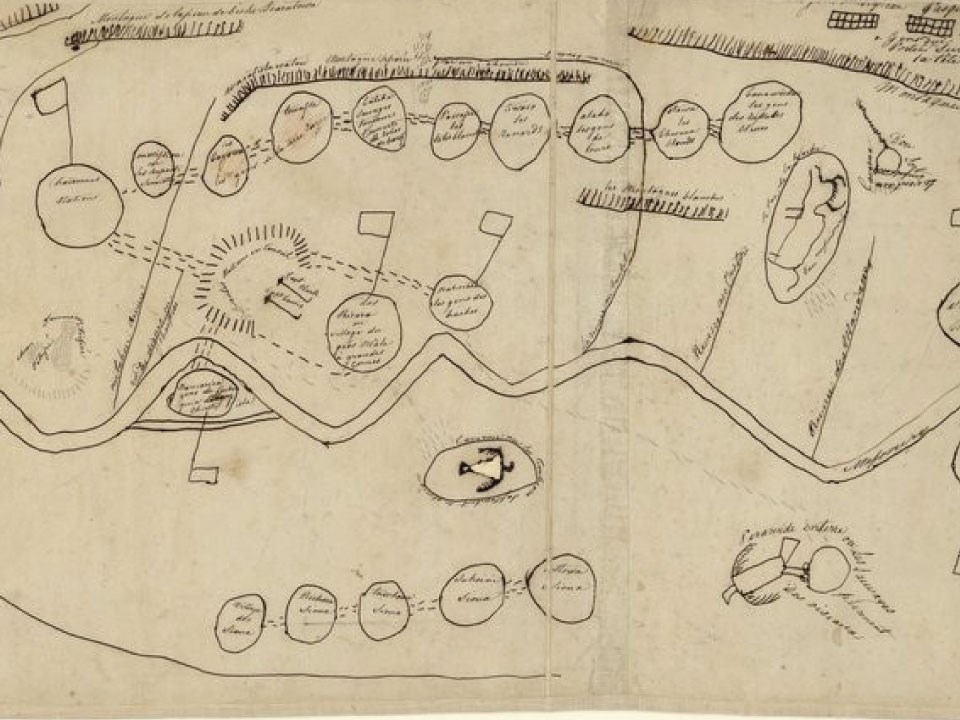

Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Joseph Gravelines is mentioned several times in Clark’s journal. While he had been living with the Arikaras since around 1790 (DeMallie et al.), on October 8, 1804, Clark complemented Gravelines as a ‘man well versed in the language of the nation,’ referring to the Arikaras. Gravelines then briefed the expedition on the country and people who inhabited it (Clark). Gravelines was mentioned again two days later when Gravelines and Tabeau had breakfast with Clark. Possibly referring to the October 10, 1804 mention of Gravelines in Lewis’ journal, Vaugeois suggested that Lewis and Clark met with much success on account of Pierre Dorion, who had lived with the Sioux Yanktons for many years, and therefore performed a critical assignment for the expedition. Dorion may have been absent during this brief period which required Gravelines’ services. Vaugeois (157) suggested that the pressure was on Gravelines and Tabeau to perform well interpreting. The interpreting that Gravelines performed took place near present-day Mobridge, South Dakota (Morris).

Waiting to meet with local chiefs, Clark dispatched Gravelines to invite the chiefs to council with Lewis and Clark (Clark). On October 18, 1804, two men employed by Gravelines complained to Clark that the Indians had been pilfering their traps, furs, and other articles (Clark). Clark wrote on November 6, 1804 that Gravelines was ordered to ‘take on the Arikaras in the spring,’ but continue to construct the huts out of cottonwood (Clark). During this time, Clark joined Gravelines and an Arikara chief, Too Né, as they walked along the shore of the Missouri. Gravelines described the animals, their migration patterns, and where they wintered (Ronda, xi). In addition, Né relayed the traditions held by his people regarding turtles, snakes, and the wise power of a rock or cave on the next river. Clark was dismissive of such stories, and declared them ‘not worth mentioning’ (Ronda, xii). Ronda argued that if Clark had not been so dismissive, researchers would have had a much clearer perspective on the cartography and ethnography of the area at that time (xiii).

Early the next year, Gravelines appeared in Clark’s journal on February 28, 1805. Gravelines and five others arrived with letters from Anthony Tabeau regarding the Arikaras’ peaceful intentions. Gravelines also informed Clark about the hostile intentions of the Sissetons and three Teton bands. Gravelines also told Clark of the Sioux who had robbed his party of two horses. The Arikaras returned the favor by denying the Sioux food, which was considered an insult (Clark). Captain Lewis wrote highly of Gravelines, calling him ‘honest, discreet, and an excellent boatman.’

Sometime after March 11, 1805, there was a falling-out between Toussaint Charbonneau and the leaders of the expedition. Lewis and Clark informed Charbonneau that his demands were unsatisfactory. Consequently, the expedition hired Gravelines in his place. After Charbonneau realized his mistake, he rejoined the expedition around March 17, 1805. Gravelines stayed on (Nelson, 22, 23). Lewis also wrote that Gravelines would bring a few of the Arikara chiefs to Washington (Lewis, April 7, 1805). Sometime after this point, Gravelines worked with the Arikara Chief Too Né to construct a map of the Arikara world (Jenkinson). According to Steinke (589) Gravelines translated the descriptive place names on the map of the Arikara nation, drawn by Too Né.

The expedition met Gravelines with a Sioux interpreter, Mr. Dorion. On September 12, 1806, Clark read the instructions that the President had given Gravelines and Dorion. The Arikara chief had died in Washingon, and Gravelines had instructions to teach agriculture to the Arikaras, though Cox (35) wrote that Gravelines was to teach agriculture to the Sioux. Dorion had instructions to accompany Gravelines (Clark). Gravelines also brought $300 worth of gifts, a letter of condolence from the President regarding the death of Chief Too Né. Gravelines had the responsibility of informing the Arikaras that their Chief had died (Jenkinson). The Arikaras were upset, and the death of their chief only added to their frustrations in their war with the Mandans. Consequently, Gravelines was found to have been ‘ill-treated’ after delivering the news to the tribe (Expedition, 437; Saindon, 431).

After the expedition, little is known of Gravelines. Researchers suspect that Gravelines did not remain long with the Arikaras since Indian hostilities increased between the Natives and Euro-Americans. Upset with taking Native land and lack of natural immunity from communicable diseases, eventually even the fur traders were no longer welcome on Indian lands. However, Gravelines was at least partly responsible for allowing the expedition’s return through Indian country safer (Saindon, 431).

Interpreters such as Gravelines and Tabeau served not only a vital function for the expedition, but also in providing a history of the tribes they encountered. Gravelines and Tabeau explained to Lewis and Clark that the Arikaras were once members of the tribes that were at one point related to the Pawnees, but had since separated. The languages had diverged from the original Pawnee. However, Gravelines and Tabeau served Lewis and Clark during their successful councils with the Arikaras (William).

References

- Clark, William. “October 8, 1804 Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition.” Lewisandclarkjournals.unl.edu, lewisandclarkjournals.unl.edu/item/lc.jrn.1804-10-08#lc.jrn.1804-10-08.01. Accessed 21 Oct. 2021.

- Clark, William. “October 10, 1804 Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition.” Lewisandclarkjournals.unl.edu, lewisandclarkjournals.unl.edu/item/lc.jrn.1804-10-10. Accessed 21 Oct. 2021.

- Clark, William. “October 18, 1804 Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition.” Lewisandclarkjournals.unl.edu, lewisandclarkjournals.unl.edu/item/lc.jrn.1804-10-18. Accessed 21 Oct. 2021.

- Clark, William. “November 6, 1804 Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition.” Lewisandclarkjournals.unl.edu, lewisandclarkjournals.unl.edu/item/lc.jrn.1804-11-06. Accessed 21 Oct. 2021.

- Clark, William. “February 28, 1805 Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition.” Lewisandclarkjournals.unl.edu, lewisandclarkjournals.unl.edu/item/lc.jrn.1805-02-28#lc.jrn.1805-02-28.01. Accessed 21 Oct. 2021.

- Cox, Isaac Joslin. The early exploration of Louisiana. Vol. 2. No. 1-4. University of Cincinnati Press, 1906.

- Clark, William. Journals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition, September 12, 1806. (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press / University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries-Electronic Text Center, 2005). https://lewisandclarkjournals.unl.edu/item/lc.jrn.1806-09-12#lc.jrn.1806-09-12.02

- Clark, William. Journals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition, October 2, 1804. (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press / University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries-Electronic Text Center, 2005). https://lewisandclarkjournals.unl.edu/item/lc.jrn.1804-10-02#lc.jrn.1804-10-02.02

- DeMallie, Raymond J., and Gilles Havard. "Writing the history of North America from Indian country: The view from the north-central Plains, 1800-1870." Journal de la Société des Américanistes 105.105-1 (2019): 13-40.

- Expedition, Lewis and Clark. Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition: With Related Documents, 1783-1854. Edited by Donald Jackson, 2nd ed., University of Illinois Press, 1978.

- Jenkinson, Clay. “Joseph Gravelines Discovering Lewis & Clark ®.” www.lewis-Clark.org, www.lewis-clark.org/article/2311. Accessed 21 Oct. 2021.

- Lewis, Meriwether. “April 7, 1805 Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition.” Lewisandclarkjournals.unl.edu, lewisandclarkjournals.unl.edu/item/lc.jrn.1805-04-07#lc.jrn.1805-04-07.02. Accessed 21 Oct. 2021.

- Morris, Larry E. "We Descended with Great Velocity." The Fate of the Corps. Yale University Press, 2008. 5-22.

- Nelson, W. Dale. Interpreters with Lewis and Clark: The Story of Sacagawea and Toussaint Charbonneau. University of North Texas Press, 2003.

- Ronda, James P. Finding the west: Explorations with Lewis and Clark. UNM Press, 2006.

- Saindon, Robert, editor. Explorations Into the World of Lewis and Clark. Digital Scanning, 2003.

- Steinke, Christopher. "“Here is my country”: Too Né's Map of Lewis and Clark in the Great Plains." William & Mary Quarterly 71.4 (2014): 589-610.

- Vaugeois, Denis. "Toussaint Charbonneau." Recherches Amérindiennes Au Québec, vol. 37, no. 2, 2007, pp. 157-159,175. ProQuest, https://lopes.idm.oclc.org/login?url= https://www-proquest-com.lopes.idm.oclc.org/scholarly-journals/toussaint-charbonneau/docview/1697228472/se-2?accountid=7374.

- William, Glenn. "For the Want of an Interpreter - Lewis and Clark - Corps of Discovery - U.S. Army Center of Military History." U.S. Army Center of Military History, 31 Jan. 2021, history.army.mil/lc/The%20People/interpreter.htm#end9. Accessed 5 Nov. 2021.

Last updated: May 20, 2022