Last updated: September 4, 2020

Article

John Rudolph: The Forgotten Son

Lake County Historical Society

During the course of the Civil War thousands of families sent their sons off to battle. It was fairly common for a mother and father to send two or three boys to the fight, increasing the odds that one or more would not return home. The Rudolph family of Hiram, Ohio saw both their sons, John and Joe, enter the Union army. Joe sought immediate adventure by joining the infantry while John, being the older and probably wiser, found a job with the Ohio Quartermaster Corps. Already the father of two young children, John’s position as wagon master kept him away from any duty at the front. Driving supply wagons seemed like a good idea to increase one’s chances of staying alive.

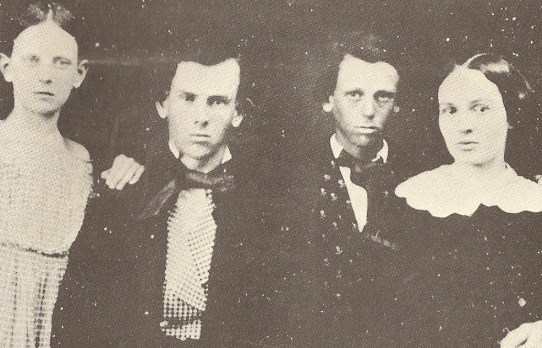

John Rudolph was born in 1835, the second child of Zeb and Arabella Rudolph. The family had a farm in Garrettsville, Ohio where John had some schooling and did his part clearing fields and harvesting crops. In 1850 the Rudolphs moved to nearby Hiram where John and his older sister Lucretia had the opportunity to get a better education.

Library of Congress

There is little information about John’s activities in Hiram; however we do know in 1856 he married Martha Lane and set off on an adventure west to Iowa. Why he left his family and tried homesteading so far away is open to conjecture. Possibly he lived in his father’s shadow and decided he wanted to be his own man. Zeb was a big player in Hiram, one of the founders of the Western Reserve Eclectic Institute (later Hiram College), a preacher, farmer, and carpenter. There may not have been room for John.

While in Iowa, a daughter, Adelaide, was born. The Rudolphs did not stay long in the Hawkeye State, moving east to the small town of Princeton, Illinois. The most prominent resident of Princeton was Owen Lovejoy, a congressman and close friend of Abraham Lincoln. (Over the years the town would be home to a diverse group of residents, including actor Richard Widmark and musician Keith Knudson, longtime drummer for the Doobie Brothers.)

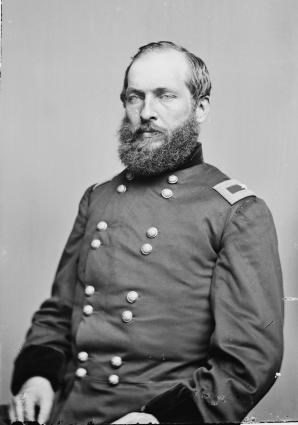

John had apparently given up farming, taking a job as a clerk. A short time later a second child, Gilbert, was born. By 1861 the Rudolphs were back in Hiram during which time the Civil War began. John, like most of the Hiram boys, had the option of joining the 42nd Ohio Volunteer Infantry (OVI), the regiment of his brother-in-law, Lieutenant Colonel James. A. Garfield. Instead, in June of 1862 he chose to go the safer route, answering an advertisement to drive wagons for the Ohio Quartermaster Corps. He must have had a great deal of skill with horses and wagons that led him to the job of wagon master. Here he would be in command of drivers and supplies vital to the Union army.

That same month, Private Rudolph led twelve supply wagons to eastern Tennessee, then on to the Cumberland Gap on the border of Kentucky, Virginia, and Tennessee. Union General George Morgan and his troops were holding the major passageway, but were in desperate need of food. Among the regiments at the gap were the 42nd OVI and John’s brother, Joe Rudolph. It is not recorded but quite likely the two brothers had a chance to visit for a brief moment. If they did, it was the last time the two would ever see each other.

After the journey to Cumberland Gap, John became seriously ill. High fever, severe diarrhea and bouts of delirium set in. He was sent to the army hospital in Lexington, Kentucky. Further examination revealed typhoid fever for which there was no effective treatment. During the course of the war thousands of soldiers on both sides were struck down with typhoid, usually dying within four to six weeks. Many of the soldiers drank tainted water which carried the deadly bacteria. John’s time was short.

The Rudolphs soon received word of John’s illness. His mother Arabella and sister Lucretia made their way to the hospital in Lexington. Martha Rudolph was unable to travel due to the imminent birth of twin boys, Louis and Ernest. While she reluctantly stayed home with her four children, John gave up the fight and died on August 12, 1862. He had been in the Quartermaster Corps a total of three months. His mother brought the body home for burial in Hiram. This scenario was unfortunately played out with families all over the country. Thousands of children were raised in the post-Civil War days without the benefit of a father.

Martha Rudolph chose to stay in Hiram where her children had aunts and uncles and cousins all around. Nearly ten years after John’s death she applied for a widow’s pension with the federal government. She had assistance from Congressman James A. Garfield and Hiram College President Burke Hinsdale. The request went to the Committee on Invalid Pensions for consideration and vote. On April 23, 1872 the petition was read to the committee. A congressman from Maryland asked for an explanation of the request. It was revealed that John was never mustered in the army. At the time of John’s service, wagon masters were considered part of the army and subject to the benefits of a soldier. However in September of 1862 the army changed its stance and no longer recognized wagon masters as regular army. John’s death prevented him from mustering in to military service. The matter was further discussed but due to additional objections the petition was tabled.

Congressman Garfield was present for the committee hearings. He remained silent for the proceedings, which was contrary to his usual participation. Due to his relationship with the petitioner, it is likely he decided not to voice his opinion. Perhaps there was politics in play. The Congressman who objected to the pension request was a Democrat; Garfield, of course, was a Republican. Whether or not that was the case, the petition was moved to indefinite postponement.

Library of Congress

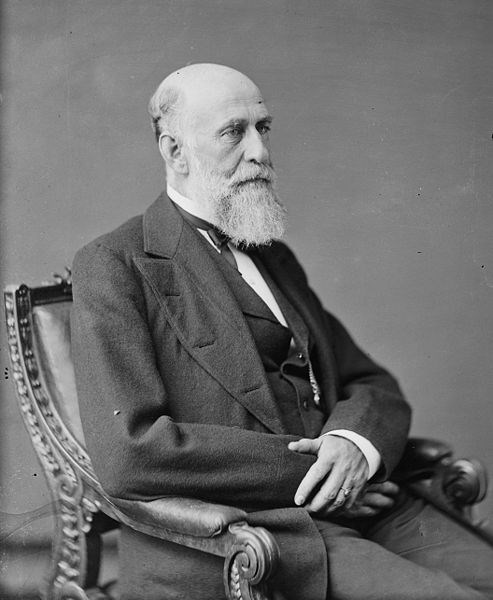

At a later date, Senator George Edmunds, a Republican from Vermont and an old friend of Garfield, introduced a resolution to reconsider the pension request. Edmunds stated, “Some additional evidence has been furnished which may change the complexion of the case.” Who furnished this evidence and why was Senator Edmunds involved? Possibly the congressman from Hiram had called in a few favors behind the scenes? A vote was taken and the resolution was passed.

Within days the Committee on Invalid Pensions brought the Rudolph pension request back to the floor. Senator Daniel Pratt reported the new evidence satisfied the committee that Martha Rudolph was entitled to her request. On June 1, 1872 both the House and Senate voted to grant a pension of eight dollars monthly to John’s widow. In addition, she would receive two dollars monthly for each child until they were adults. The record stated, “That the name of Martha G. Rudolph widow of John Rudolph be placed on the rolls to receive the pension now provided by law for the widows of enlisted men who died in the service and in the line of duty.”

Martha and her children remained close to the Rudolph and Garfield families. Whenever Congressman Garfield left Washington and took a train to the Hiram area, usually one of John Rudolph’s boys would pick him up at the depot. They may have owed him a small debt of gratitude for the “evidence” that cleared the way for their mother‘s pension. Regardless of how the pension was granted, one thing is for certain; John Rudolph earned it.

Thanks to Dan Reigle of the Cincinnati Civil War Roundtable for locating the pension papers for John Rudolph.

Thanks to Bill Stark

Rudolph pension files from the National Archives, Washington D.C.

Written by Scott Longert, Retired Park Guide, James A. Garfield National Historic Site, August 2013 for the Garfield Observer.