Last updated: May 30, 2021

Article

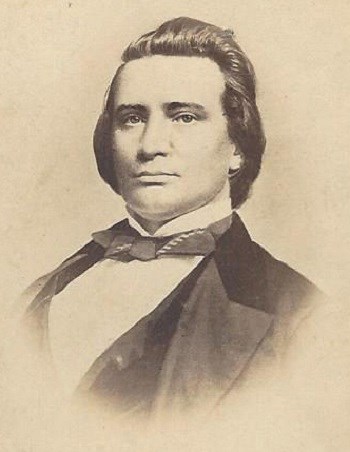

John Logan: War Hero, Public Servant, Founder of Memorial Day

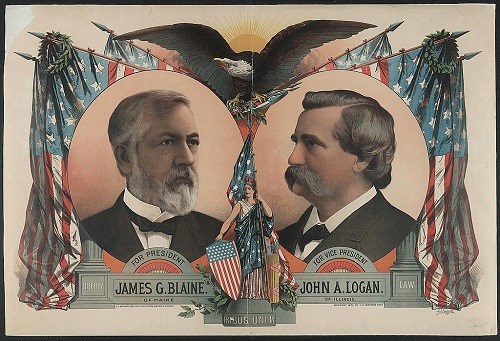

John Logan lived a very full life of public service. He was a successful and active politician at the local, state, and national levels. He was also an effective military leader who fought in many significant engagements of the American Civil War. He went on to become the head of the Grand Army of the Republic, a fraternal organization for veterans of the Civil War. In that role Logan is credited with establishing Memorial Day as a national day of remembrance for those who lost their lives in the Civil War.

General John A. Logan Museum

Early politics and the Mexican-American War

John Alexander Logan was born February 9, 1826 in what is now Murphysboro, Illinois, and what was then a pro-slavery region in the southern part of the state. His father was a local politician, elected three times to the Illinois General Assembly, serving almost a decade. Both men were staunch Jacksonian Democrats.When the Mexican-American War started, Logan joined Co. H 1st Regiment Illinois Volunteers. He served from 1847-48, marching with his unit from Fort Leavenworth, Kansas to Santa Fe, New Mexico. He did not see any combat, but almost died from the measles.

He returned to Illinois and won his first political office as a clerk in Jackson County in 1849. He was 23 years old. After graduating from the University of Louisville in 1851, he was elected as the prosecuting attorney of the Third Judicial District of Illinois.

A year later, Logan wanted to get back into politics and won a seat in the Illinois 18th General Assembly. Mirroring the pro-slavery views of his constituents, Logan was responsible for the passage of a bill to prevent free blacks from entering Illinois. Revealing his racist views, he stated that “It was never intended that whites and blacks should stand in equal relation.” Most of the residents of Southern Illinois agreed, and so it seems did the majority of Illinois; the state-wide vote to allow the exclusionary law won by a two-to-one margin. However, “Logan’s Black Law” did not endear him to the anti-slavery residents of Illinois.

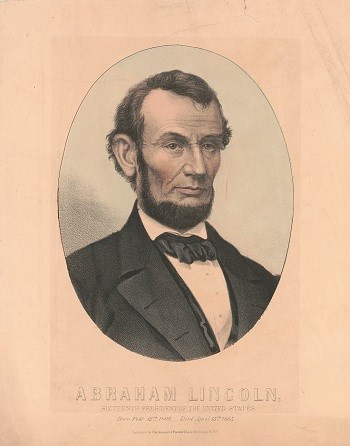

He went on to be elected to the United States House of Representatives as a Democrat, in 1858, receiving nearly 80 percent of the vote. He was elected again in 1860. His pro-slavery views were aligned with his southern colleagues in the House. However, he did not agree with the secession movement that took hold in the months after Abraham Lincoln was elected president in 1860-61. Logan believed that the Union needed to be preserved and his work towards compromise brought accusations of disloyalty among some of his colleagues in the Democratic Party.

Library of Congress

The Civil War Begins

The Confederacy fired on the United States garrison of Fort Sumter, South Carolina on April 12, 1861 launching the Civil War. Three months later, United States Congressman John Logan joined others from the nation’s capital who brought picnic baskets and wine to Manassas Junction, Virginia on July 21. They went out to watch what was expected to be a quick victory for the Northern Army in the first full-scale engagement of the war. Instead, it was stinging and bloody defeat, with over 2800 Union casualties.Unable to sit and watch the Union army being beaten, Logan ran onto the field of battle as an unattached volunteer for a Michigan regiment. After witnessing the devastating defeat, he went back home and organized the 31st Illinois Volunteer Infantry Regiment, becoming its colonel.

In an August 1861 speech in Marion, Illinois Logan announced that he had volunteered with the Federal army, and encouraged his fellow citizens to join him in saving the Union. Ulysses S. Grant later said that this influential speech was effective in convincing the people of Southern Illinois to stay aligned with the Union. Now a member of the United States military, Logan had to resign his congressional seat, which he did in 1862. This took Logan out of politics until the war ended. Unlike other politicians-turned-soldiers, John Logan excelled in the military.

He led the 31st in its first engagement at Belmont, Missouri (November 1861). Collectively, they received accolades for bravery from Grant. In February 1862 Logan and his regiment distinguished themselves again at the Battle of Fort Donelson, Tennessee. But unfortunately, Logan was wounded three times in this battle. After spending several weeks in a field hospital, he went home to recover.

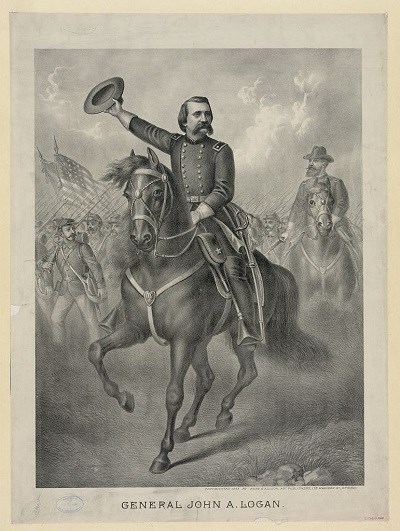

During this time, Grant recommended that Logan be promoted. Logan would return to the front as a Major General, successfully commanding a division during the campaign to capture Vicksburg, June-July, 1863.

Another act of heroism by Logan came a year later when General James McPherson, Logan’s superior officer, was killed in the early stages of the Battle of Atlanta, July 22, 1864. Logan stepped in under pressure to restore leadership on the battlefield, and took command of the Army of the Tennessee. Even though Logan’s actions turned a Union rout into a victory, he was subsequently replaced as head of the Army of the Tennessee by West Point graduate Major General Oliver O. Howard. It was later presumed that this was because William T. Sherman was skeptical of politicians in uniform.

Library of Congress

Logan supports Lincoln for President in 1864, Returns to Politics

Logan’s views on slavery and African Americans changed throughout the war. After President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in January 1863, he urged fellow Union soldiers to accept the recruitment of African American volunteers. Logan’s change from Democrat to Republican was made official by the fall of 1864 when he returned to Illinois to campaign for the re-election of President Abraham Lincoln.After Lincoln’s reelection, Logan was sent to Raleigh, North Carolina to become the last commander of the Army of the Tennessee. He was in Raleigh when he received word of the assassination of President Lincoln at Ford's Theater. In Raleigh, as elsewhere throughout the country, the murderous act in Washington, DC triggered more violence. A mob of 2000 angry federal soldiers stormed toward the city, bent on revenge. Logan personally stood in the way, threatening to open fire if they did not disperse. The soldiers retreated to their camp, and Logan is still celebrated by North Carolinians for saving their capital. Logan would later manage the impeachment trial of Lincoln’s successor Andrew Johnson, who, ironically, had been born in Raleigh in 1808.

Library of Congress

Logan wasted no time in returning to politics. The post-war Logan was a legislator with very different views. He voted for Constitutional amendments to abolish slavery and to grant citizenship and voting rights to African Americans. He also supported Women’s Suffrage.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

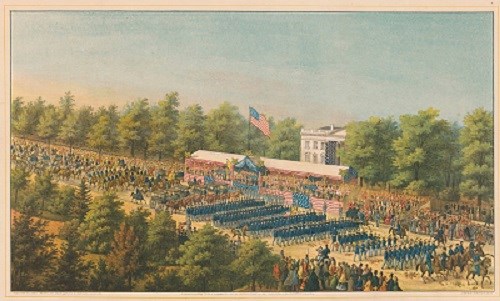

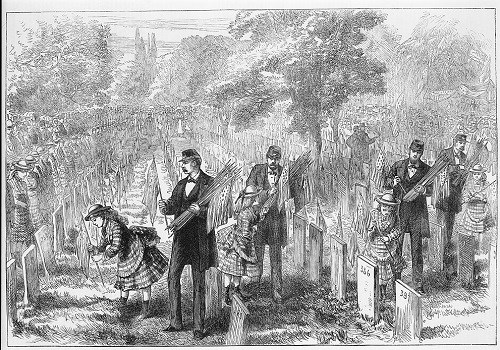

The Origins of Memorial Day

As the death toll mounted throughout the four-year conflict, residents of the south began to decorate the graves of their fallen loved ones with flowers, fabric and flags. This evolved into an annual event called “Decoration Day.” The ritual of decorating the graves of soldiers spread throughout the entire country.In addition to his political work, Logan was a founding member of the Grand Army of the Republic, America’s first national veteran’s organization. It was in that role that he formalized “Decoration Day” by issuing General Order Number 11 in 1868. The order designated May 30 as an annual national holiday “for the purpose of strewing with flowers or otherwise decorating the graves of comrades who died in defense of their country.” It is believed that May 30 was selected because flowers would be in bloom all over the country.

After World War I, Memorial Day became a day to honor the fallen from ALL American wars. In 1971, Memorial Day was declared a national holiday by Congress, and moved to the last Monday of May.

Library of Congress

Family

John Logan married Mary Simmerson Cunningham on November 27, 1855. She was 16 years old, and the daughter of his commanding officer during the Mexican-American War. He was 29. They were life-long partners, and had three children: John (died as an infant), Mary Elizabeth (Dollie), who married and had two children, and Manning (later called John II), who also married and had three children.John A. Logan died on December 26, 1886. He laid in state in the United States Capitol Rotunda and was buried in Washington’s Soldiers’ Home National Cemetery. His wife Mary lived another 37 years, and is buried next to her husband.

Logan Circle, Washington, DC – A National Park site

Back in John Logan’s neighborhood in Washington, DC, he is remembered. In 1930, Congress renamed “Iowa Circle” in Logan’s honor, the location of his home that still stands at 4 Logan Circle. This eight-block area surrounds a circular park that features a large bronze statue of the Civil War hero. The area contains over 100 residences that were constructed between 1875-1900, showcasing an almost solid frontage of Late Victorian and Richardsonian architecture. The district was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1972.Anyone who has ever driven in DC knows about its infamous traffic circles. But Logan Circle is the city’s last remaining fully-residential one. Today Logan Circle is managed by the National Park Service and is a vibrant and lovely greenspace used by residents and visitors. At the center of Logan Circle, and across the street from Logan’s residence, stands a bronze equestrian statue of John A. Logan. Its base is sculpted with figures representing Peace and War, and scenes from Logan’s lifetime of public service. Logan sits high on a horse, dressed in his full military uniform.

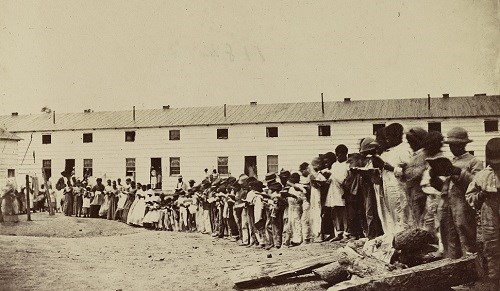

National Archives

During the Civil War, this very location was the home of Camp Barker, a military barracks that was converted into a refugee camp for newly freed slaves. President Lincoln would make stops at this camp just north of the capital city on his commute to the Old Soldier’s Home. A cottage at the Soldier's Home provided his family a quiet and cool respite during the summer and a welcome relief from the busy daily routine of the wartime White House.