Last updated: October 6, 2021

Article

John Hoskins Stone and the Revolutionary War

Thomas Stone National Historic Site

Despite being a signer of the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Stone may not have been the most accomplished of the eight Stone brothers born at the Maryland plantation of Poynton Manor in the mid-1700s. This acclaim may belong to his younger brother, John Hoskins Stone, who was a successful trader, lawyer, officer in the Revolutionary War, and after the war, the seventh governor of the state of Maryland.

The Stone family plantation of Poynton Manor was only a few miles west of the town of Port Tobacco. The town was a major terminus for the Atlantic trade and the local warehouses stored tobacco, grain, and other goods grown at the extended Stone family’s nearby properties. Equally important, Port Tobacco was the seat of government for Charles County and where generations of Stones served as judges, lawyers, and elected officials.

It was into this family of planters, traders, and lawyers, that John Hoskins Stone was born in 1750. With his privileged family connections, Stone received a private education as a youth and learned the duties expected of him as part of Maryland’s gentry. Stone’s pursuit of a legal career might have been inevitable with his being mentored by his older brother Thomas Stone, who was recognized as one Maryland’s most successful lawyers.

On March 25, 1774, the British retaliated for the Boston Tea Party by closing the Port of Boston, and the resulting blockade soon caused misery and suffering in Massachusetts. To show their “Common Cause,” the people of Maryland and the other colonies created non-importation “associations” to hurt the British economy by not ordering British goods. A few went further by suggesting a non-exportation of colonial goods going to Europe.

As a merchant and a lawyer, John Hoskins Stone consulted with the residents of Port Tobacco who worried that bans on exports and imports might financially ruin the community’s planters. He concluded that “Our Patriots are blazing away about the Boston affairs, but I think they will not resolve upon non-exportation…” of Maryland tobacco, grains, and other goods.

Realizing that many Colonials, like those in Port Tobacco, were either Loyalists or reluctant to challenge the authority of the King, George III, and the British Parliament, a plan was enacted to develop a communication network. With his various connections, John Hoskins Stone was an ideal candidate to serve on the Maryland “Committee of Correspondence.” Soon, he was relaying information up and down the Atlantic Coast, which showed that the onerous taxes, the threat of military action, and the potential loss of rights was a shared concern in all thirteen of the colonies.

The Committee of Correspondence opened the way for the colonies to unite. Concerns at the local level were equally important. John Hoskins Stone served on the Committee of Observation, which monitored the citizens of Charles County to ensure no one was flaunting the non-importation laws or profiting while others patriotically did without. More importantly, he supported the decision to prohibit the collection of debts during that time of economic instability.

In the summer of 1775 as the situation with Great Britain deteriorated, John Hoskins Stone and his brother, Thomas, represented Charles County at the Maryland Convention in the capital of Annapolis. This was a meeting of representatives from across Maryland, who formed a parallel government to the one presided over by Maryland Governor Robert Eden for Great Britain.

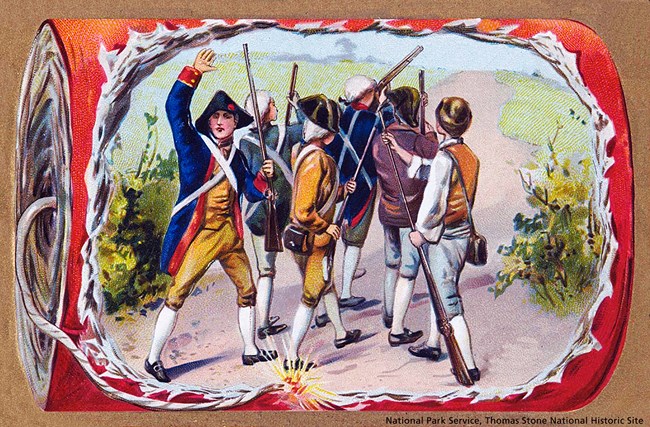

While Maryland was not yet ready to declare its independence, the two brothers signed the “Declaration of the Association of the Freemen of Maryland.” As “Freemen,” the Marylanders vowed that “as one band” they would fight the “uncontrollable tyranny” of Great Britain and that they do so “by Arms,” and by legal means of a “continental association.” Within a matter of months, John Hoskins Stone took up “Arms” as an officer in the First Maryland Regiment, while Thomas Stone was representing Maryland in the Continental Congress in Philadelphia.

John Hoskins Stone was at many of the Revolutionary War's most significant battles; Brooklyn, White Plains, Trenton and Princeton, Brandywine, and Germantown. At the Battle of Germantown in October, 1777, Stone received a wound in his ankle which ended his active service in the military.

Stone went into politics, serving in Maryland's Senate and as a judge before being appointed as the seventh governor of the state of Maryland in 1794. During his tenure, Stone established policies that are still followed today. Stone served three one-year terms as governor.

Stone died on October 5, 1804, seventeen years to the day after his brother Thomas' death.