Part of a series of articles titled West Virginia Mine Wars.

Previous: The Battle of Blair Mountain

Article

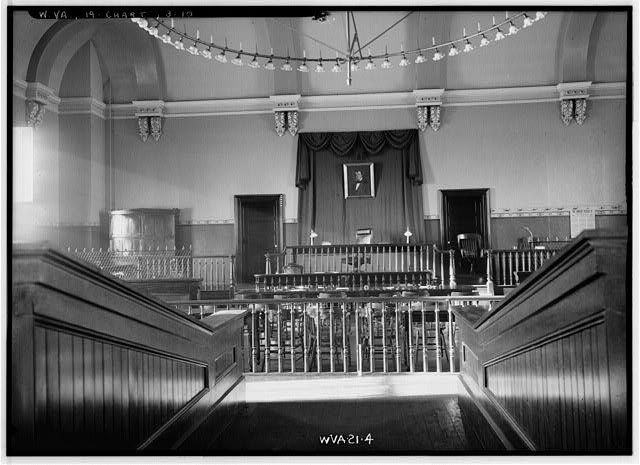

National Park Service Photo/Susan Salvatore 2019

During the two centuries that the Jefferson County Courthouse has existed in Charles Town, West Virginia, it has hosted two nationally significant treason trials. In 1859 it served as the setting for militant abolitionist John Brown’s treason and murder trial after his ill-fated raid on the Federal armory at Harpers Ferry. The courthouse where Brown was convicted was heavily damaged in the Civil War and substantially rebuilt between 1871 and 1872. During the spring and summer of 1922, the second-floor courtroom of the 1872 courthouse witnessed another treason trial, that of coal miner and union activist William Blizzard and his compatriots, which, like that of John Brown, captured the attention of the nation.

In the aftermath of the Battle of Blair Mountain, a union-led coal miner’s strike that led to the largest pitched battle in American labor history, West Virginia Governor Eli Morgan sought federal charges against the union miners who had surrendered to federal troops. The federal government declined to bring charges, and instead continued an ongoing Senate investigation into conditions in the coal counties. When federal charges failed to materialize, the state of West Virginia took up the mantle of prosecuting the miners. During the winter and spring of 1922, the state indicted over 500 miners on charges of murder, conspiracy to commit murder, accessory to murder, and treason against the state.

While there were multiple indictments, the charge that received the most attention was that of treason against the state of West Virginia, which was leveled against 20 members of the United Mine Workers (UMW) District 17, which actively worked to unionize the West Virginia coal fields throughout the early 1900s. The stakes of the trials were high, not just for the workers in the state, but also for the struggling labor movement as a whole. The key fear among labor leaders was that if the prosecution prevailed, the draconian anti-union tactics revealed by these trials would be legitimized and could spread to other industries in regions far beyond the borders of West Virginia.

The Binghamton Press

The trials, initially to be held in the state’s coal-mining region, were moved to Jefferson County—over 250 miles away by train—in an attempt to insure an impartial jury. Jefferson County had no coal mining operations, and thus was seen as neutral territory for the trial. From the outset, the treason accusations were on shaky legal ground. Believing that the charges were “improper,” the prosecutor for Jefferson County, John T. Porterfield, recused himself and declared that the trials as a whole were “a waste of scarce resources and mean-spirited vendettas.” In his place stepped private attorneys C. W. Osenton and A. M. Belcher, referred to as the “Coal Dust Twins” by the miners because of their close working relationship with the mine operators. Thomas Townsend, a lawyer for the UMW, led the defense team along with Harold Houston, who had worked closely with District 17. While the accused sat in jail, Houston went to work raising funds for their legal defense. This effort began well before the indictments were issued. During the march on Logan, Fred Mooney, the secretary-treasurer of UMW District 17, helped to establish the Mingo County Defense League. Many responded to the national, and global call for donations to the “Miners Defense Fund,” and soon the fund amassed over $50,000.

The funding of both the defense and the prosecution illustrates the wider issues that undergirded the mine wars. The money raised on behalf of the accused miners demonstrated the support they received from the labor movement, even among industries wholly unconnected to coal mining. While organized labor paid for the legal defense of the accused miners, the coal mine operators supplied the immediate funding for the prosecution (although they would later bill the state for $125,000 in legal fees). For the duration of the trials the prosecuting attorney for Jefferson County and the state attorney general did not participate. As such, to many observers, the state abdicated its legal responsibility to private coal barons.

The first to be tried was Bill Blizzard who was charged with treason against the state. The sheer amount of media attention paid to the treason trials, particularly Bill Blizzard’s trial, turned these regional labor issues into a national conversation. Media coverage was most extensive in coal-rich Pennsylvania, as papers from cities and towns like Altoona, Allentown, Scranton, Indiana, Lebanon, Wilkes-Barre, and New Castle reported daily on the progress of the trial. The Scranton Republican was the most comprehensive in its reporting. Several papers in New York City also kept their readers apprised of the trials, with the Brooklyn Citizen and the New York Times covering the daily events, reporting on who testified and the key details of each testimony.

Understandably, much of the press emphasized the significance of the treason trials for the labor movement. The UMW had the most at stake in the outcome of the trials, as evidenced by the presence of John Lewis, the president of the UMW, who sat at the defense table rather than in the audience.

Library of Congress/HABS

The trial rested on the legal merits of the prosecution’s indictments. Because the first trial pertained to the charge of treason, Blizzard’s case set the standard for the rest of the proceedings. By most accounts, Blizzard was the leader of the march; but the question being disputed at his trial was whether he was at the helm when the marchers reached Blair Mountain. Throughout the trial, witnesses for the prosecution and defense presented conflicting testimony. Some miners who had turned state’s witnesses against their compatriots testified that Blizzard was commanding the miners’ army during the entire march to Logan County and the Battle of Blair Mountain. Witnesses for the defense, however, claimed to have seen Blizzard in Charleston during the march, while others said that Blizzard helped to broker the marchers’ surrender after the army interceded. The defense’s star witness was an U.S. Army infantry captain who stated that he never heard any miners talk of going to war against the government; rather, they sought to “protect the women and children” from Chafin’s deputies in Logan County.

Blizzard’s trial, which lasted for over four weeks, ended in acquittal. After the verdict came down on May 25th, miners and local sympathizers celebrated in Charles Town. Later that day, sympathizers in Charleston, the state capital, feted Blizzard with a parade. Rather than simply exonerate Blizzard, some contemporary observers claimed that the verdict had deeper implications. A writer for the Duluth Herald commented, “In a large measure the state of West Virginia was on trial in the Blizzard case and the verdict of acquittal as to Blizzard was equivalent to a verdict of ‘guilty’ against the state.”

The treason trials that played out at the Jefferson County Courthouse in 1921 were a major turning point in the West Virginia mine wars and the American labor movement. While the Battle of Blair Mountain and its aftermath drew national attention to West Virginia miners and their fight for basic rights as laborers and citizens, the lengthy and expensive treason trials ended the decade-long fight in the coalfields of the state. At the conclusion of the trials, District 17’s treasury was nearly depleted and local union leadership could no longer support the mining families that were continuing to strike throughout the state. Ultimately, UMW national leaders decided to completely cut off additional funding for District 17 and Keeney’s two year mining strike was officially ended.

In the economic slump that followed the immediate post-World War I boom, labor unions across the nation saw a decrease in overall membership. The defunding of the UMW in West Virginia effectively halted the fight against coal mine operators’ abuses and mining families continued to suffer under the mine guard system. Wages for West Virginia miners plummeted throughout the 1920s creating a dire situation for workers in the lead up to the Great Depression. It was not until the election of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the passage of labor-friendly New Deal laws that workers in the West Virginia coal fields and across the nation would finally gain the right to fully unionize.

The Jefferson County Courthouse is listed on the National Register of Historic Places (NHRP) and was designated a National Historic Landmark in 2023. The NRHP is the official list of the nation's historic places worthy of preservation. Authorized by the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, the National Register of Historic Places is part of a national program to coordinate and support public and private efforts to identify, evaluate, and protect America's historic and archeological resources. National Historic Landmarks (NHLs) are historic places that possess exceptional value in commemorating or illustrating the history of the United States. The National Park Service’s National Historic Landmarks Program oversees the designation of such sites. There are just over 2,600 National Historic Landmarks. All NHLs are also listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

View the National Register nomination for Jefferson County Courthouse and the National Historic Landmark nomination for the Jefferson County Courthouse.

Discover more resources on the West Virginia Mine Wars and related topics here: Resources on the West Virginia Mine Wars.

Part of a series of articles titled West Virginia Mine Wars.

Previous: The Battle of Blair Mountain

Last updated: September 27, 2024