Last updated: August 17, 2023

Article

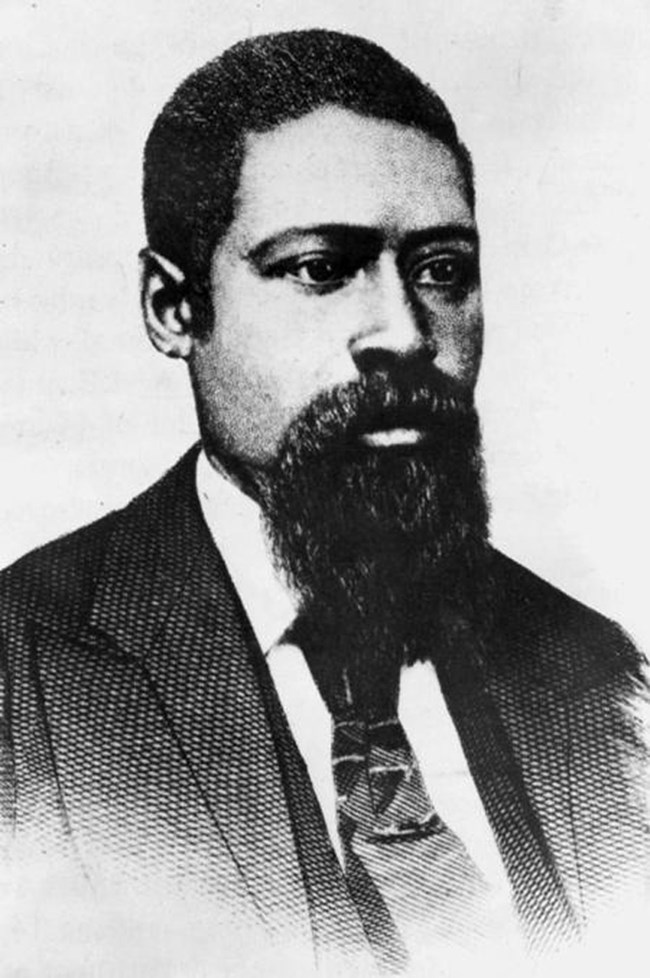

James Milton Turner: Educator and Minister to Liberia

State Historical Society of Missouri

James Milton Turner was a prominent African American politician, educator, and civil rights advocate. President Ulysses S. Grant appointed Turner as Minister to Liberia in 1871 and was the second African American to become a U.S. minister to another country.

He was born sometime between 1839 and 1840 to John and Hannah Turner. His mother was an enslaved woman owned by Reverend Aaron Young and Theodosia Young, while his father was a free black farrier (a person who works with horses). Hannah Turner’s enslaver, Theodosia Young, later freed her and her son James Milton on December 5, 1843. It is believed that Turner received much of his education at the Floating Freedom School, a school operated by John Berry Meachum on a steamboat on the Mississippi River. This arrangement was due to an 1847 Missouri state law that prohibited the education of all African Americans in the state, whether free or enslaved. Turner eventually attended Oberlin College in Ohio for a semester, but later returned to St. Louis due to financial issues.

With the breakout of the Civil War in 1861, Turner was employed as a body servant to Colonel Madison Miller of the Union Army. After suffering a hip injury during the Battle of Shiloh, Turner left his employ with Miller. After the war, Turner became involved with the Missouri Equal Rights League. As a member, he sought legislative allowance for black political and civil rights, particularly the right to vote for African American men in Missouri. He later became Assistant Superintendent of Missouri schools and helped establish the Lincoln Institute, the first institution of higher education for African Americans in Missouri. He continued his focus on education for African Americans as an agent of both the Freedmen's Bureau and the Missouri Department of Education with a specific objective in mind: to establish more public schools for African American children.

By 1871, Turner was interested in working for the federal government, specifically President Ulysses S. Grant's administration. Turner was at first rejected by Grant for the position of Minister of Liberia despite numerous recommendations from high-ranking politicians praising his familiarity with Liberian politics. However, Grant had a change of heart and selected Turner for the position after his other appointees declined the post. On May 25, 1871, Turner departed for Liberia from New York.

When Turner arrived, Liberia was dominated by two political parties: the True Whigs and the Republican Party. The True Whigs received support from wealthy citizens, particularly those born in the U.S. who had migrated to Liberia, while the Republican Party was supported by poor and working-class citizens. A small minority of “Americo-Liberian” residents dominated both parties and Indigenous residents were denied the right to vote. Domestic affairs were chaotic and as Minister, Turner’s main duty was to update the State Department of events in Liberia while simultaneously maintaining close ties with both factions.In 1875, Turner served as a mediator between the Liberian government and a confederation of the Grebo people, a native tribe within the country. Liberia requested U.S. intervention to help resolve the conflict. Turner requested military assistance to aid the Liberian government and in response, President Grant ordered a naval ship, the USS Alaska, to the country.

Another goal of Turner’s was promoting trade and diplomatic relations between the United States and Liberia. He also furthered the ties between Liberia and other countries seeking to establish Liberia’s position as a sovereign state. Reflecting his own upbringing and education in St. Louis, Turner viewed Liberians as “barbaric” people and sought to civilize them through Christianity. He also deemed the country unfit for the migration of African Americans as he believed they would find it difficult to adjust to the weather and way of life. This belief may be due to his physical struggles in Liberia as he contracted various ailments and malaria three times. In 1878, he made his way back to St. Louis.

After his return, Turner grew disillusioned with the state of American politics. He found that his political influence had declined as well. However, he remained politically active and sought to provide relief for African American refugees from the South. Turner also fought for the rights of freedmen who had been previously enslaved by the Cherokee, Choctaw, and Chickasaw tribes. He pushed for Congress to redistribute funds the government had given the Cherokee for their land to include the Cherokee Freedmen. On November 1, 1915, Turner passed away at 75, due to blood poisoning from a car tank explosion. James Milton Turner is now buried at Father Dickson cemetery (2 miles away from the Ulysses S Grant National Historic Site) and held in high regard as an eminent St. Louis historical figure.

National Park Service

Further Reading

“1847 to 1871 Nationhood and Survival.” Library of Congress. Accessed August 8, 2023. https://www.loc.gov/collections/maps-of-liberia-1830-to-1870/articles-and-essays/history-of-liberia/1847-to-1871/

Kremer, Gary R. 1991. James Milton Turner and the Promise of America : The Public Life of a Post-Civil War Black Leader. Columbia: University Of Missouri Press.

Kremer, Gary R. “James Milton Turner.” n.d. SHSMO Historic Missourians. Accessed July 25, 2023. https://historicmissourians.shsmo.org/turner-james-milton/.

Walton, Hanes, James Bernard Rosser, and Robert L Stevenson. 2002. Liberian Politics : The Portrait by African American Diplomat J. Milton Turner. Lanham, Md.: Lexington Books.