Last updated: January 23, 2021

Article

James Garfield: Congressman (Part II)

Library of Congress

The 43rd Congress

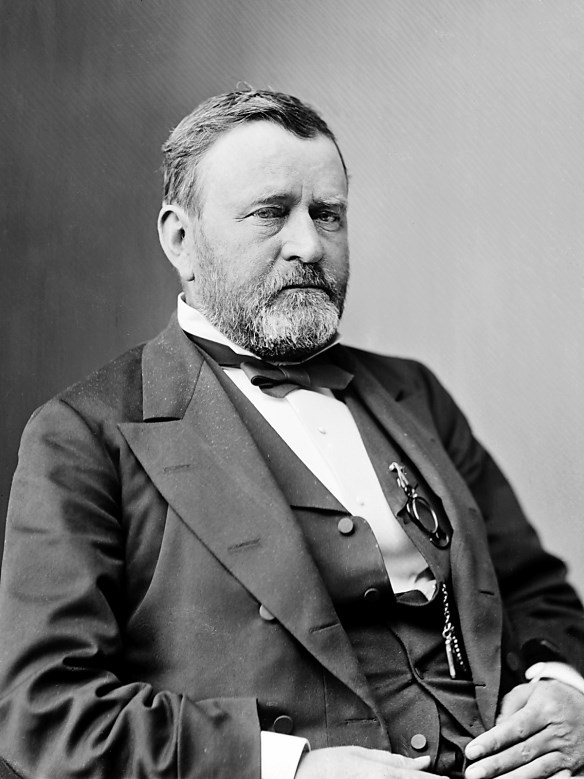

1872 was again a presidential election year, with Grant running for a second term against Horace Greeley, the candidate for a rebellious splinter group of “liberal Republicans” and the Democrats. “In my interior view of the case,” said Garfield, “I would say Grant was not fit to be nominated and Greeley is not fit to be elected.” But Garfield’s own election prospects improved with the redistricting after the 1870 census. The nineteenth district was redrawn, removing Mahoning County and adding Lake County, freeing Garfield from the “Iron men” of the Mahoning Valley, and adding another solidly Republican voting bloc. His nomination was unopposed, and his election was 19,189 votes to 8,254.

Library of Congress

The 44th Congress

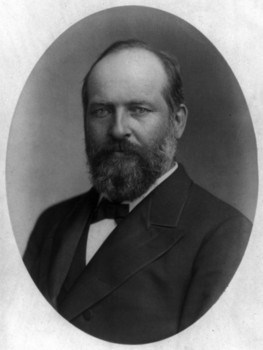

Garfield faced his stiffest challenge to re-election in 1874. Grant’s second term was consumed by scandal and mired in depression. Voters were generally in a foul, “throw-the-bums-out” mood. And in the nineteenth district local Republican conventions were passing resolutions condemning Garfield’s association with the Credit Mobilier scandal and the congressional “salary grab.” At least one local party meeting passed a resolution demanding Garfield’s immediate resignation.

For the first time, Garfield and his political friends in the district knew that they were in a real fight. In January, Garfield told Harmon Austin, his most important local advisor, that he would “abide by all your engagements, and will send you the means to pay all expenses. There are political friends here [in Washington] that will aid in raising the necessary funds if I am no able to carry the load alone.”

A third scandal involving a contract for paving the streets of Washington, D.C. added to the tense atmosphere, but the issue that most aroused the voters of the nineteeth district was the “salary grab.” As a part of the annual appropriation bill, congress had voted itself a $2,500 raise, retroactive to the beginning of the 43rd Congress. This, when the legislature was cutting programs across the government, was simple for voters to understand and vocally oppose. As chairman of the appropriations committee in the House, Garfield was seen as personally responsible for the passage of the “salary grab” even though he had opposed it in committee and on the floor of the House.

Library of Congress

So Garfield returned to his district and campaigned for delegates to the local nominating conventions, explaining his positions mostly in small meetings and through his friends. In August he wrote in his diary: “The District is very thoroughly aroused and we shall have large primary meetings. My enemies are bitter and noisy, my friends more active than ever before and full of fight.” Harmon Austin had developed an impressive political machine to meet challenge, and when voters met at the township level to choose delegates to the district convention, the Garfield forces showed up. The Congressman netted two-thirds of the local delegates, and by the time the district convention met the opposition had collapsed.

But the disaffected Republicans didn’t give up; instead they named an independent candidate, H. R. Hurlburt, to challenge Garfield and the Democratic candidate Daniel B. Woods, who had run against Garfield in his first campaign twelve years earlier. In a month of fierce political fighting, Garfield attempted to answer every question and every challenge. “I let these gentlemen know that during this campaign it was to be blow for blow and those who struck must expect a blow in return.” In refuting the queries of a questioner named Tuttle, Garfield said, “I doubt if he knew when I left him whether he was hash or jelly.”

On election day the result was Garfield 12,591, Hurlburt 3,427 and Woods 6,245. Garfield retained his seat, but a nationwide “blue wave” meant that his party lost its majority in the House. For the rest of his career in Congress, Garfield would serve in the minority.

The 45th Congress

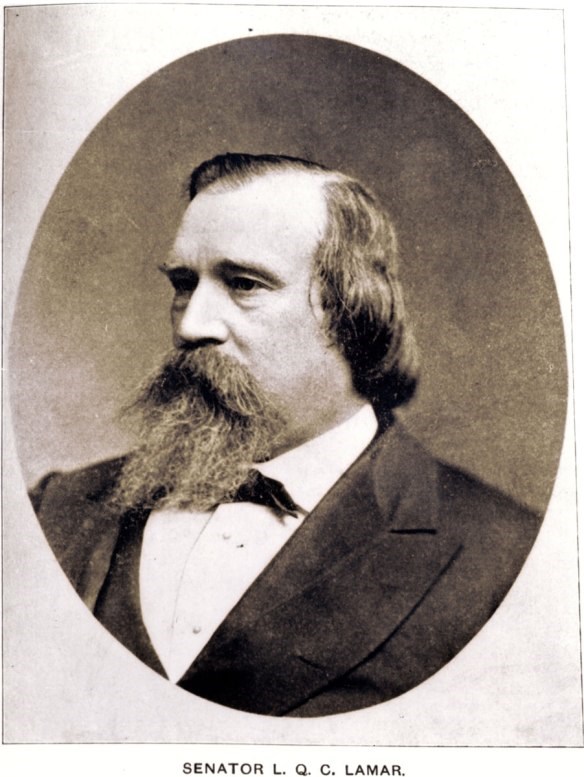

It was his position as leader of the minority that gave Garfield his springboard to the 1876 election. At the end of the congressional session that spring, Democratic Congressman L.Q.C. Lamar of Mississippi, whom Garfield respected as among the ablest Democrats in the House, delivered a carefully written and polished defense of the Democratic Party. It was immediately seen as the opening argument for the upcoming presidential campaign, when the Democrats saw their first real opportunity to win the White House since the Civil War. The next day, Garfield, as the Republican leader in the House, answered with a nearly extemporaneous response, arguing that the Democrats could not be trusted to manage the government. His speech was immediately praised by Republicans and Republican newspapers, and was reprinted for circulation everywhere.

Library of Congress

The 46th Congress

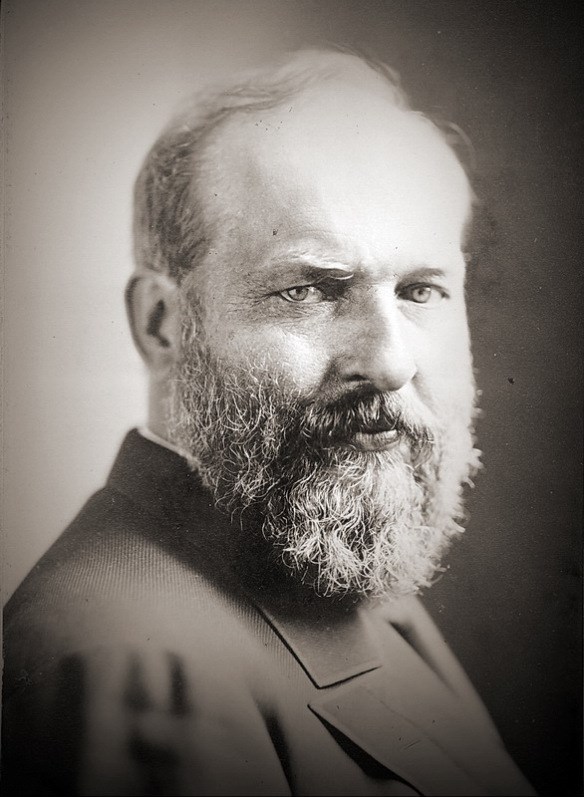

In 1878, the Ohio legislature, controlled by Democrats, redrew the state’s congressional districts for partisan advantage. Portage County, Garfield’s home for most of his life, and his original political base, was moved to another, more Democratic, district. Mahoning County, with the “Iron men” who so often disagreed with and criticized Garfield, was returned to the nineteenth.

Garfield was unanimously re-nominated by the Republicans, but he was challenge not only by a Democratic candidate, but also by an emerging Greenback party, whose candidate, G, N. Tuttle, had been one of Garfield’s loudest critics back in 1874. The main issue in the district, and across the country, was greenback currency or specie resumption. It was an issue that never seemed to be resolved, but one where Garfield’s hard money position was well know.

Garfield 17,166 Hubbard 7,553 Tuttle 3,148

The 46th Congress was the last to which James Garfield was elected. During the term of that Congress he would be selected by the Ohio legislature to serve in the United States Senate, and later that year (1880) was nominated as the Republican presidential candidate. During the nearly eighteen years Garfield served in Congress, he faced a number of issues and a variety of challenges. It is clear in looking over his congressional campaigns that he enjoyed the rough-and-tumble of campaigning, even though he often protested otherwise. Two things remained constant in Garfield’s political philosophy—his insistence on independence of judgment, and his loyalty to the Republican Party.

Written by Joan Kapsch, Park Guide, James A. Garfield National Historic Site, November 2018 for the Garfield Observer.