Last updated: October 30, 2020

Article

James Garfield: Congressman (Part I)

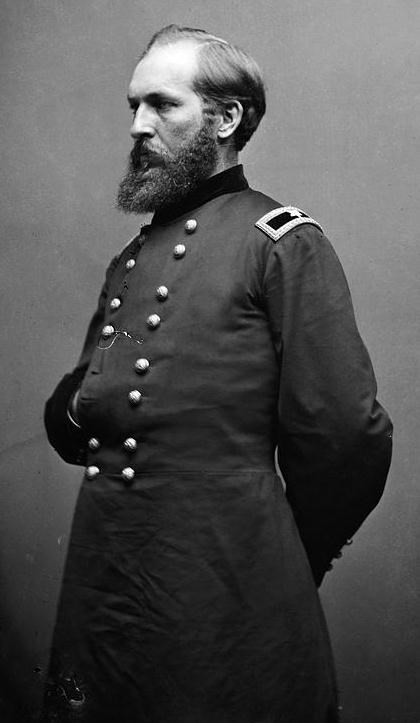

Library of Congress

In the Memorial Library at James Garfield’s home is a fancy little desk with a brass number tab. It is a Congressional desk of the style used in the House of Representatives during the early years of Garfield’s service in that chamber. It offers an opportunity to talk about his congressional career. A recent visitor asked a question we seldom hear—what were the issues in Garfield’s many congressional campaigns?

James Garfield was elected to represent northeast Ohio in the Congress of the United States nine times. His tenure in the House stretched from the last year of the Civil War to his election to the White House in 1880. The issues that faced Garfield, the voters of the nineteenth district, and the nation changed over the years, of course, as did the district itself. Here, for our visitor, is a short synopsis of the issues and challenges that faced Congressman Garfield.

The 38th Congress

Garfield first began to think about running for Congress in the spring of 1862. He was in the army at the time, serving under General Henry Halleck in the vicinity of Corinth, Mississippi. In Garfield’s view the army was bogged down both militarily and politically, neither pursuing the enemy nor liberating the slave population. He felt he could more usefully serve the country in a differ capacity, telling his friend Harmon Austin, “It seems to me that the successful ending of the war is the smaller of the two tasks imposed upon the government. There must be a readjustment of our public policy and management. There will spring up out of this war a score of new questions and new dangers. The settlement of these will be of even more importance than the ending of the war. I do not hesitate to tell you that I believe I could do some service in Congress in that work and I should prefer that to continuing in the army.”

Garfield’s home in Portage County was in a new nineteenth district, drawn after the 1860 census. Portage and Geauga were added to Ashtabula, Trumbull and Mahoning. His “friends” in the district, whom Garfield had been cultivating since his years in the state legislature before the war, told him that any “prominent men” from any of the five counties could have an equal chance at the Republican nomination. Garfield allowed his friends to enter his name in nomination, although he remained away from home and did not actively seek the nod. He won the nomination on the eighth ballot at the district convention in September.

The major issues in the fall campaign all related to the war, of course. Failures on the battlefield and the announcement of the Emancipation Proclamation divided Union voters. In the nineteenth district, one of the strongest anti-slavery districts in the country, Garfield won overwhelming support: 13,288 votes to his opponent’s 6,763. In northeast Ohio, a Republican nomination virtually guaranteed an election victory.

The 39th Congress

Two years later, the conduct of the war and the re-election of Abraham Lincoln were the issues of the election. Freshman Congressman Garfield had expressed less than full-throated support for the President, and had voted for an extension of the draft that was not popular in his district. Garfield spoke to the 19th District nominating convention in late August, 1864. “I cannot go to Congress as your representative with my liberty restricted. . . If I go to Congress it must be as a free man. I cannot go otherwise and when you are unwilling to grant me my freedom of opinion to the highest degree I have no longer a desire to represent you.” This strong statement moved the crowd to enthusiastic cheers and re-nomination by acclimation. In November, Garfield prevailed, 18, 086 votes to his opponent’s 6,315.

The 40th Congress

Election to the 40th Congress in 1866 turned on questions of reconstruction. In the district voters were unhappy with Garfield’s support for the draft through the end of the war, and for his participation in a case before the United States Supreme Court that arose out of the war. Ex parte Milligan was the first case James Garfield ever argued in court. It revolved around the question of whether civilians arrested for aiding the Confederacy should be tried in military tribunals or in civilian courts. Garfield told a constituent, “I knew when I took the Indiana case (Milligan and several other were arrested by the Army in Indiana) that I would probably be misunderstood, but I was [so] strongly convinced of the importance of the decision of the case on the right side, that I was willing to subject myself to the misunderstanding of some, for the sake of securing the supremacy of the civil over the military authority.” Some of his constituents saw it as a “defense of traitors” and many believed it conflicted with the Radical Republican plan for reconstruction in the South.

Once again Garfield was re-nominated by acclamation, and he spent most of the fall campaign outside the district, stumping for Republican candidates in close Congressional districts in Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, Illinois and New York. The goal was to elect enough Republicans to defeat any veto by President Johnson and install a Radical reconstruction program. Not only did Garfield win, 18,598 votes to 7,376 in his district, he help secure a “magnificent victory” for Republicans across the country. “I trust,” he said, “Congress may be able to preserve the fruits of victory.”

The 41st Congress

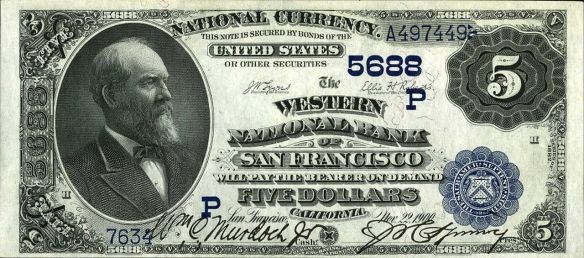

On May 15, 1868 Congressman Garfield took the floor of the House to deliver a carefully prepared speech about “the currency question.” Since the end of the war, Garfield had focused his attention on the “new questions and new dangers” of a peacetime economy based on fiat currency—that is, a national currency that was not back by gold. Political sentiment in Ohio, and particularly in the nineteenth district favored inflationary greenbacks, but Garfield argued against focusing on unbacked paper currency as the only, or even the main cause of the prosperity and industrial growth of the war years. The speech served to explain the reasons he felt it was important to return to “sound money,” and to challenge his opponents at home.

During the 1868 campaign, Garfield and his political friends distributed copies of his speeches in Congress on the currency, the tariff, and Reconstruction. The result: Garfield 20,187 votes, McEwen 9,759.

oldcurrencyvalues.com

The 42nd Congress

Protective tariffs, particularly on iron products, were the campaign issue of 1870. Garfield’s constituents in Mahoning County were demanding high tariffs on imported iron goods, or that he be replaced “by a gentleman who is at heart true to the protective tariff interests of his country.” All through the spring, the “iron men” search for a candidate to oppose him, but by June Garfield was able to report, “So far as I know there is to be no organized opposition in the convention. The Iron men tried every means in their power to secure a candidate but failed. The will probably sullenly acquiesce in the inevitable.”

Other issues included reducing the size of the army and the problems of reconstruction. On that topic, Garfield was not optimistic. “We have now reached a critical period in our legislation when we are called upon to perform the final act, to complete, for better or for worse, the reconstruction policy of the government. . . I confess that any attempt at reconciling all we have done. . . so as to form consistent precedents for any theory given to legislation is, to my mind, a failure. There are no theories for the management of whirlwinds and earthquakes.”

Garfield 13,538 Howard 7,263

(Check back for Part II soon!)

Written by Joan Kapsch, Park Guide, James A. Garfield National Historic Site, August 2018 for the Garfield Observer.