Last updated: January 23, 2021

Article

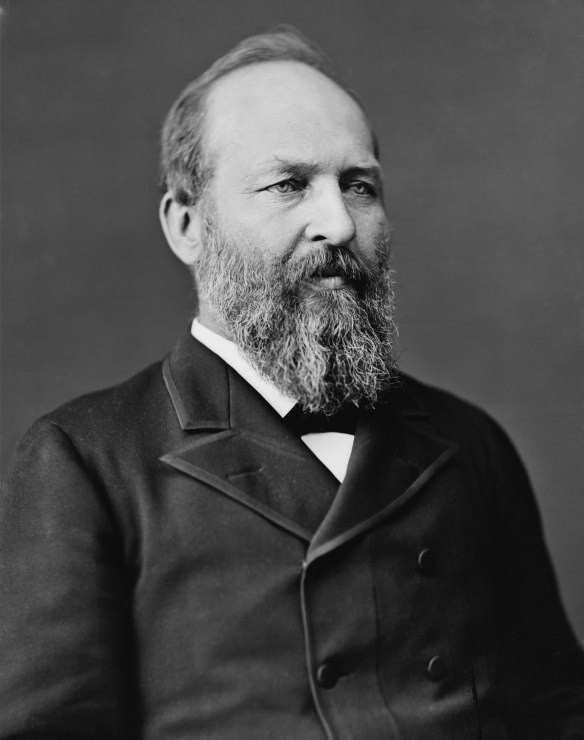

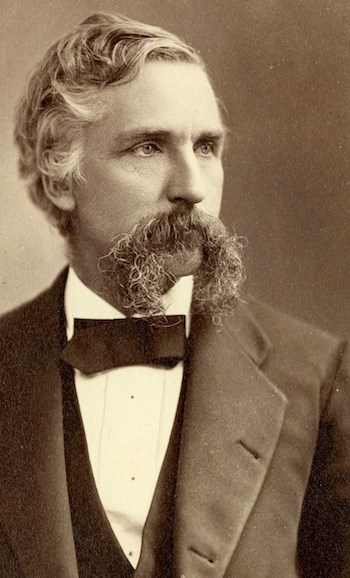

James Garfield and Joshua Chamberlain

Library of Congress

On June 14, 1881, Joshua L. Chamberlain of Brunswick, Maine, wrote a letter to President James A. Garfield. The President’s wife, Lucretia Rudolph Garfield, had been ill with malaria for much of the spring, and Chamberlain offered this advice:

It has been suggested to me by a medical gentleman of much experience

that the best treatment Mrs. Garfield could have would be a summer on

the coast of Maine. Should that judgment commend itself to you I shall

be very glad if it may be in my power to aid in the selecting [of] a suitable

place, or in any way to contribute to your satisfaction in regard to the

matter.

Chamberlain, then president of his alma mater, Bowdoin College, also invited the President to attend Bowdoin’s commencement on July 14. It was public knowledge that Garfield was heading north in less than three weeks to speak at his own alma mater, Williams College in Massachusetts, and then enjoy a vacation. The President was more than ready for a little time away from the White House. He had only recently won a hard-fought political victory regarding patronage appointments with members of his own Republican Party, most notably Senator Roscoe Conkling of New York. His wife’s severe illness added to his worries and made his first few months as the nation’s twentieth president even more difficult.

Bowdoin College

Garfield never made it to Williams or his vacation. On July 2, 1881, as he walked through Washington, D.C.’s Baltimore and Potomac train station to board his train north, Charles Guiteau approached and shot him twice from behind. The first bullet grazed Garfield’s arm, but the second lodged in his back. Over the next eighty days, doctors unschooled in Listerian antisepsis and germ theories—or willfully ignoring them—poked and prodded Garfield with dirty fingers and instruments, introducing infection into his body. The President died on September 19, eighty days after Guiteau’s attack.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

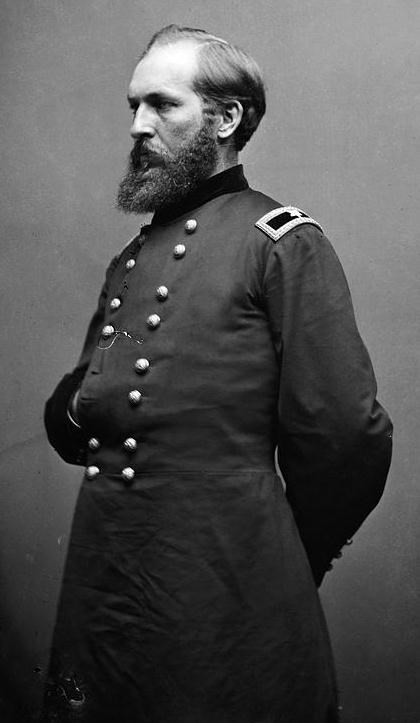

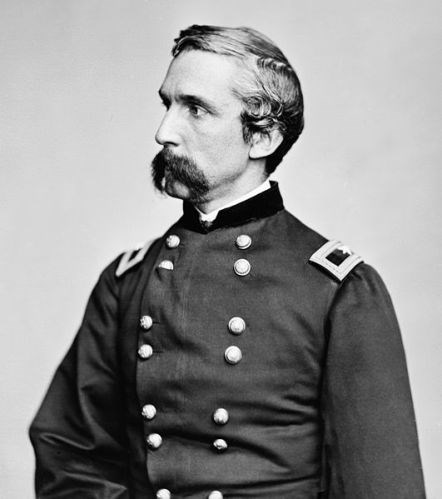

Chamberlain and Garfield both had successful careers as scholars at their alma maters before the Civil War, Chamberlain at Bowdoin and Garfield at Ohio’s Western Reserve Eclectic Institute (now Hiram College), which he attended before Williams. Both taught many different subjects and were proficient in several languages, including Greek and Latin. When the Civil War came and both were moved to volunteer for the Union, each determined to use books on military history and tactics to teach himself how to lead and fight. As Chamberlain told the Governor of Maine in a letter that could just as easily have been written by the Ohioan Garfield, “I have always been interested in military matters, and what I do not know in that line I know how to learn” (emphasis in original). Soon after, Lt. Col. Chamberlain was second in command of the 20th Maine Infantry. Garfield, a state senator at the time of the Fort Sumter attack, taught himself drill on the lawn of the Ohio Capitol Building before being assigned command of the 42nd Ohio Volunteer Infantry.

James Garfield saw action mostly in the western theater, Chamberlain in the east. During his service in the army, northeast Ohio Republicans elected Garfield to the U.S. House of Representatives, and Garfield left the army in December 1863 to go to Congress. Chamberlain remained in the army until war’s end, suffering numerous wounds that would affect him for the rest of his life. When the war ended, he was elected to four consecutive one-year terms as Maine’s governor. While Garfield enjoyed political success, though, Chamberlain’s ambitions to serve as a U.S. Senator were stymied. The Garfields and Chamberlains both endured the pain of losing children to early deaths, and both became sought-after speakers on the post-war lecture circuit.

Had Garfield survived Charles Guiteau’s assassination attempt, or had Guiteau never struck at all, perhaps Garfield and Chamberlain may have met at some point—maybe even on Garfield’s New England visit in July 1881. We can only guess, but knowing a little bit about their backgrounds and life experiences makes it a good bet that they could have been fast friends.

Written by Todd Arrington, Site Manager, James A. Garfield National Historic Site, March 2017 for the Garfield Observer.