Last updated: October 30, 2020

Article

James A. Garfield and the Lincoln Assassination

Wikipedia Commons

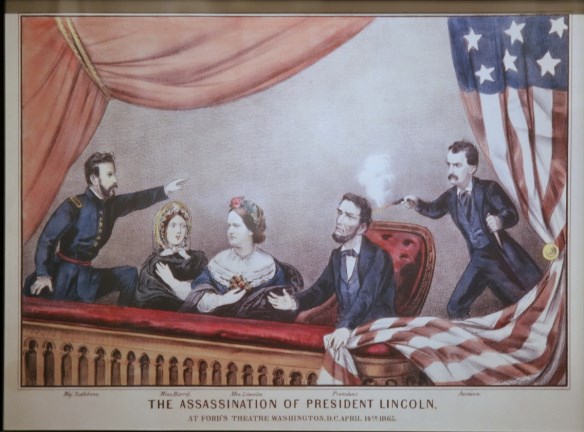

One hundred and fifty years ago, on April 14, 1865, John Wilkes Booth committed what many consider the last tragic and violent act of the American Civil War. That evening, he snuck into the presidential box at Ford’s Theater in Washington, D.C., where President and Mrs. Abraham Lincoln were enjoying the third act of the comedy Our American Cousin. Booth was a well-known actor from a family of well-known actors, and he had little trouble gaining access to the box. He drew a small Derringer pistol, pointed it at the back of Lincoln’s head, and pulled the trigger.

As the theater erupted into noise and chaos, Booth leapt from the box onto the stage, supposedly screaming “sic semper tyrannis” (thus always to tyrants) as he jumped. Despite breaking his leg when he landed, Booth escaped. He was tracked down and killed by federal troops in Virginia almost two weeks later. The mortally wounded President Abraham Lincoln was carried across the street to the Petersen House, where he died about nine hours after being shot. His hopes and plans for a lenient, easy Reconstruction of the South died with him. Radical Republicans in Congress quickly wrested control of Reconstruction from President Andrew Johnson and inflicted a harsh, punitive program on the South that led to more than a century of hard feelings and distrust.

Dickinson College

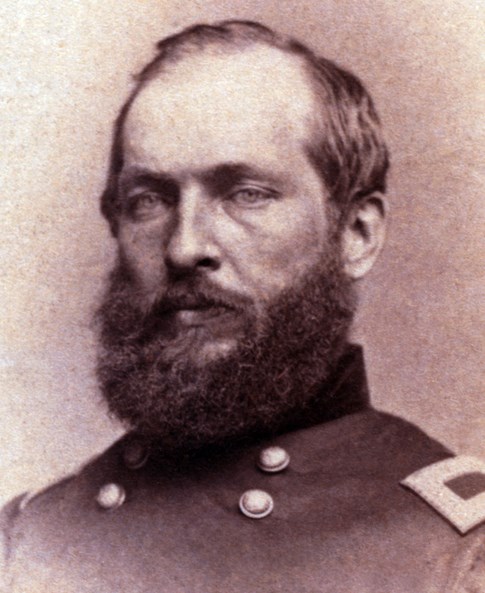

James A. Garfield was a 33-year old freshman congressman when Lincoln was murdered. A former Union general, Garfield had been nominated by Ohio Republicans and won election to the House of Representatives while still in the field with the army. He left the military at the end of 1863 to take his seat in the House. On April 14, 1865, Garfield was on a trip to New York City. He learned of Lincoln’s death the next morning and wrote to his wife, Lucretia: “I am sick at heart, and feel it to be almost like sacrilege to talk of money or business now.” Though Garfield had disagreed with President Lincoln on several issues, he was clearly distressed by the violent death of the man whose leadership had seen the United States through its darkest days.

Over the years, a story emerged about Garfield’s actions in New York after learning of Lincoln’s death. Like so many other places across the North, New York City was in chaos after the news of the President’s murder began to spread. Anger, sadness, and fear gripped many of the city’s residents as suspicions of a conspiracy and the expectation of more killings ran rampant. Supposedly, a mob of some 50,000 people filled Wall Street and screamed for the heads of southern sympathizers. As the story goes, the crowd had just resolved to destroy the offices of The World, a Democratic newspaper, when a single figure appeared above them on a balcony and began to speak: “Fellow citizens! Clouds and darkness are round about Him! His pavilion is dark waters and thick clouds of the skies! Justice and judgment are the establishment of His throne! Mercy and truth shall go before His face! Fellow citizens! God reigns, and the Government at Washington still lives!”

These are the words supposedly spoken that day by Congressman James A. Garfield. A supposed eyewitness to this event reported “The effect was tremendous,” and that Garfield’s words brought calm to the crowd (and saved The World’s office from destruction, one assumes). This witness then turned to someone close to ask who the speaker was, and was told, “It is General Garfield of Ohio!”

historicpages.com

This story became famous and, as historian Allan Peskin relates, “an enduring aspect of the Garfield mythology.” Regularly re-told by newspapers under the heading “Garfield Stills the Mob,” it was widely circulated in Garfield’s later political campaigns, including his 1880 run for the presidency. Sadly and ironically, it was also regularly mentioned in memorial pieces after Garfield was, like Lincoln, murdered by an assassin. However, like so many great stories, there is little reliable evidence to suggest that it happened as reported.

Several things about the story make it unlikely to be completely true. First and foremost, despite being a lifelong diarist and letter writer, James A. Garfield himself never mentioned it. Surely some version of it would have made it into a letter or diary entry at some point. There was also no spoken or written tradition within the Garfield family that lent any authority to this event. (Garfield himself may have elected not to discount the story after he saw how valuable it was during campaigns.) Secondly, the same story with nearly the same quotes from Garfield later gained traction as having taken place during the Gold Panic of 1869. James A. Garfield was nowhere near New York City during that event, but eyewitnesses still claimed to have watched him speak from a balcony and calm thousands of panicked stockbrokers. Finally, Garfield’s eldest son, Harry A. Garfield, tried unsuccessfully to authenticate the story by searching the archives of New York newspapers. Allan Peskin writes: “Both the Tribune and the Herald covered the Wall Street meeting and gave what purported to be verbatim accounts of a speech delivered by Garfield. Although both versions contain echoes of the famous speech, neither version matches the eloquence or brevity of the speech of the legend, nor is there any indication that Garfield’s words pacified an angry mob although, according to the Herald, a lynch mob was calmed shortly before the meeting by Moses Grinnell.”

So what are we to make of this story? In all likelihood, it is just that: a story. Garfield may very well have offered a few words to the New York crowd that day, but the image of him calming an angry mob with religious allegories and assurances that the federal government would survive the calamity of Lincoln’s death is very likely a myth. Like so many events in history, the story took on a life of its own, especially when Garfield became both a presidential candidate and then a martyred leader. While the story makes Garfield a more appealing and attractive historical figure, it ultimately does him a disservice by making us appreciate him for something that never happened. There is plenty to admire about James Garfield; we don’t need apocryphal stories to make him more appealing.

Written by Todd Arrington, Chief of Interpretation & Education, James A. Garfield National Historic Site, April 2015 for the Garfield Observer.