Last updated: January 23, 2021

Article

James A. Garfield and the Civil War (Part II)

Library of Congress

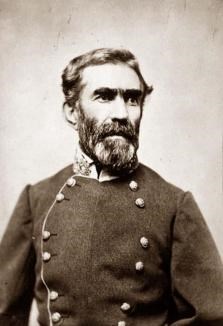

Garfield was summoned to Washington when his health was restored. After several months of inactivity, he received an offer from General William Rosecrans, the commander of the Army of the Cumberland, to join his staff. Garfield arrived in February 1863, reporting to Rosecrans’s headquarters in Murfreesboro, Tennessee. Rosecrans had just won a victory over Confederate General Braxton Bragg at Stones River and was planning to advance towards Chattanooga, a rebel stronghold.

While Rosecrans waited for more supplies, Garfield accepted the position of Chief of Staff to the Army of the Cumberland. He urged Rosecrans to move quickly while the weather was clear, but Rosecrans hesitated. Garfield grew impatient and urged his boss to send out some cavalry raids. Garfield got permission and planned two raids himself, but both met with failure. Heavy criticism came from the regular army generals on Rosecrans’s staff.

Washington became impatient as well. President Lincoln wired Rosecrans to move quickly against General Bragg and his forces. The commander called a meeting of his generals to get their opinion on an attack. Almost the entire staff cautioned Rosecrans about making any kind of an advance. Garfield, however, disagreed and wrote Rosecrans a detailed report explaining why an immediate attack would be successful. The report cited the weakness of the Confederate army due to Grant’s siege of Vicksburg. No additional Rebel troops could be spared. Rosecrans agreed with Garfield, calling for an assault June 24th. The plan had Garfield characteristics all over it, including simultaneous attacks from the flanks, then a major assault in the center. The plan caused confusion in the Confederate ranks and Bragg retreated 18 miles south the Tullahoma.

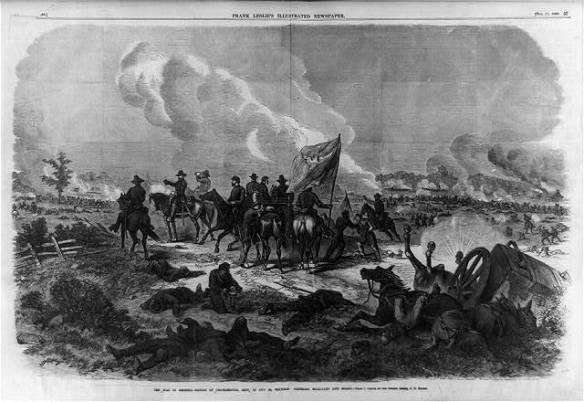

The Union army pressed forward. Chattanooga was in sight, but again Rosecrans hesitated another two months. Garfield believed another quick attack would destroy Bragg’s army. He wrote Secretary Chase citing his displeasure with his commanding officer. Finally, Rosecrans decided to advance towards Chattanooga. Using some tactics that were similar to Garfield’s successful Middle Creek campaign, Rosecrans’s men lit campfires for non-existent camps, floated wood downstream to give the appearance of building bridges, and sent cavalry behind Bragg’s line.

Library of Congress

Though Garfield had little to do with the battle, one of his officers would later say that he performed like a true General, giving encouragement to the troops throughout the fight. For his action a promotion to Major General would follow.

In the fall of 1863, Garfield left the army and returned to Washington, D.C., where he soon took his place in Congress. He would remain in the House of Representatives for seventeen years, until his 1880 election as the twentieth President of the United States. Despite re-entering civilian life, he never lost touch with the military. Garfield attended reunions of the 42nd Ohio until his death in 1881. He became close friends with General William Tecumseh Sherman. As President, he appointed Major Don Pardee of the 42nd to a federal judge position. Colonel Lionel Sheldon, who assumed command of Garfield’s old regiment, was given the job of territorial governor of New Mexico. Though long since gone from the army, Garfield remained a military man at heart.

Written by Scott Longert, Park Guide James A. Garfield National Historic Site July 2012 for the Garfield Observer.