Last updated: October 25, 2020

Article

James A. Garfield and the Civil War (Part I)

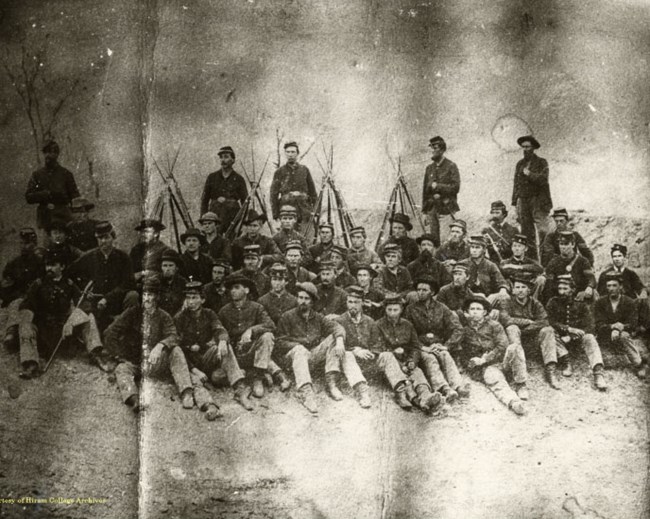

Hiram College Archives

The Civil War began in April 1861 while James A. Garfield was principal of the Western Reserve Eclectic Institute (now Hiram College) and a state senator living part-time in Columbus. The November 1860 election of Abraham Lincoln led several southern states to secede from the Union. Many southerners feared the election of Lincoln would bring an end to slavery, even though Lincoln was not an abolitionist in 1861. He had stated many times that he would leave slavery alone in the southern states, but would not permit any expansion of it to the new western territories. Lincoln and many other northern politicians supported the policy of admitting new states to the union as free states only. Southerners believed they were entitled to bring slaves with them if they chose to settle in any of the western territories. Despite attempts at compromise, the differences could not be overcome, leading to the bombardment of Fort Sumter and the start of the Civil War.

Like many political figures of the day, James Garfield sought a commission as an army officer. These politicians viewed themselves as leaders of men and thus were convinced they were officer material. Garfield hoped for command of a regiment. He told his roommate, future Brigadier General Jacob Cox,

“I am big and strong, and if my relations to the church and the college can be broken, I shall have no excuse for not enlisting.”

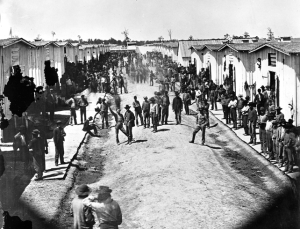

National Archives (111SC108919)

After an unsuccessful attempt to be voted in as Colonel of the 7th Ohio, Garfield waited several months until he received an offer from the Governor to be Lieutenant Colonel of the 42nd Ohio Volunteers. He accepted the commission and then went about recruiting soldiers to fill out the regiment. Company A was filled almost entirely with Eclectic Institute students loyal to their ex-principal Garfield. Many of the students knew they would eventually enlist and decided to throw in with a man they admired and respected.

With help from staff officers Lionel Sheldon and Don Pardee, the 42nd’s ranks were filled, allowing the men to report to Camp Chase for training. Garfield received a promotion to full Colonel for his recruiting efforts. Studying every book he could find on drill techniques and battle formations, Colonel Garfield was able to train his men quickly and soon received orders to leave for Kentucky to face a small force of Confederates gathering for a possible assault on Louisville and then Cincinnati.

General Don Carlos Buell commanded the Department of Ohio. In December 1861, Garfield travelled to Louisville to meet with Buell and get his orders. He was instructed to draw up a plan of battle and submit it to Buell the next morning. He stayed up all night studying maps of Kentucky and drew up plans for an attack. Buell liked what he saw, awarding Garfield the command of three additional regiments, one from Ohio and two from Kentucky. A small unit of cavalry accompanied the newly formed brigade. The 42nd and the new additional regiments left for Catlettsburg, Kentucky on December 19, via the Ohio River. Upon arrival a supply base was assembled there that would remain throughout the campaign. The regiments then marched 20 miles south to the town Louisa to set up camp.

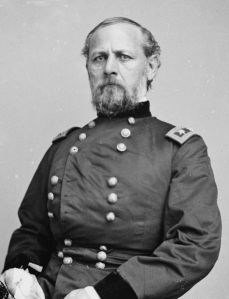

The Confederates opposing Garfield’s command were led by General Humphrey Marshall, an 1832 graduate of West Point and a veteran of the Mexican War. His headquarters were in Paintsville, 30 miles south of Garfield’s position. Marshall had three infantry regiments with him, plus artillery.

Garfield’s strategy was to send the 40th Ohio west to get behind Marshall, while the remaining regiments would attack from the front, catching the Confederates in a vise. Garfield attacked in early January 1862, sending three small companies to attack the left, front, and center of Marshall’s lines. This maneuver confused Marshall, who wrongly assumed he was under attack by 4,000 Union troops. He ordered a retreat south, evacuating Paintsville without a fight.

University of Kentucky

Several days later, Garfield attacked Prestonsburg. His regiments had to ford across ice-cold creeks to get into position. Marshall’s men were entrenched in a mountain range south of Middle Creek. Unable to determine the Confederates’ location, Garfield sent cavalry dashing across the valley. The startled southerners opened fire and revealed their position. The attack lasted until nightfall, with the 42nd leading a last-minute assault up the crest of the mountain.

Darkness ended the battle, but before Garfield could resume the attack at daybreak, Marshall burned his supplies and retreated all the way to Virginia. Though the battle had ended in a draw, Garfield had accomplished his plan, clearing the Confederate regiments out of Kentucky. All that was left was a rearguard at the Virginia border. In March, Garfield moved south and attacked the rearguard, sending them retreating to Virginia and ending the campaign.

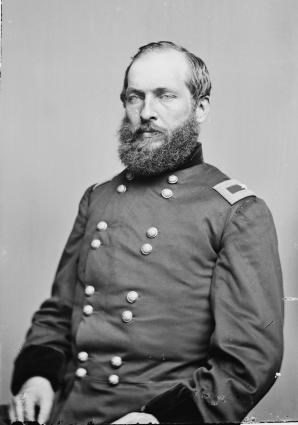

Library of Congress

For his efforts, Garfield received a promotion to Brigadier General and a new command of the 20th Brigade, operating in Tennessee. The 20th saw action on the second day of fighting at Shiloh. By then, the Confederates were in full retreat. The 20th gave chase, exchanging fire with the rearguard. Though there were no casualties, Garfield’s men managed to pick up 40 prisoners.

In August 1862, camp fever and dysentery forced General Garfield to take leave from the army. He returned home to Hiram for a long period of recuperation. While home, friends of Garfield persuaded him to let his name be brought forward as a candidate for the United States House of Representatives. Garfield himself stayed behind the scenes, but won a victory as a Republican congressman. He did not have to report to Washington for a full year, which allowed him to remain in the army temporarily.

To be continued…

-Scott Longert, Park Guide