Last updated: September 4, 2020

Article

James A. Garfield and “Rain Follows the Plow”

Lake County Historical Society

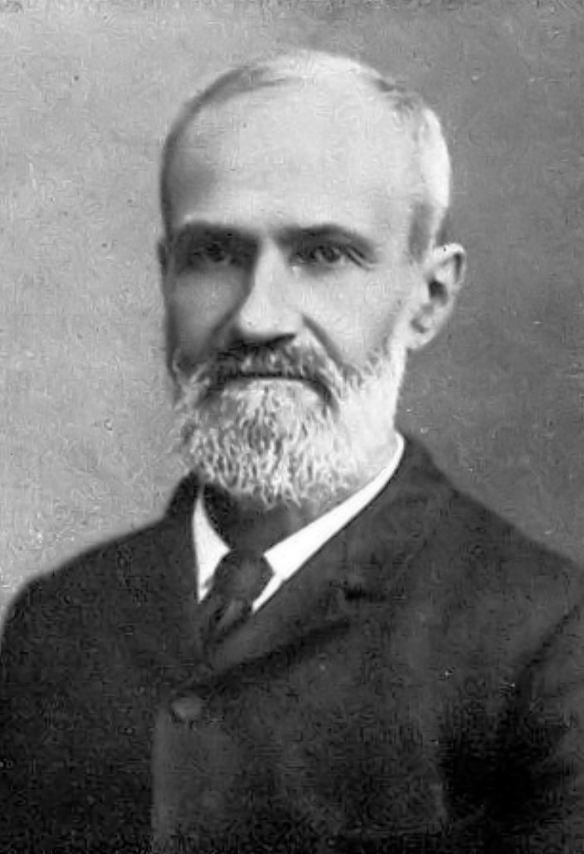

James A. Garfield pursued many vocations during his relatively short life of 49 years and ten months, including canal worker, janitor, minister, college professor and president, lawyer, soldier, congressman, and President of the United States. Less well-known, though, is his lifelong interest in agriculture, which prompted him to purchase a 120-acre farm in Mentor, Ohio in 1876. “I must get a place where I can put my boys at work, and teach them farming,” he wrote in his diary on September 26, 1876. After purchasing the property, Garfield wrote his wife, Lucretia, “So, my darling, you shall have a home and a cow.” Today, about eight acres of that farm and its buildings are preserved as James A. Garfield National Historic Site. Here Congressman Garfield grew wheat, rye, and barley, and also had an orchard of apple and peach trees.

In early June 1880, Garfield traveled to the Republican National Convention in Chicago to nominate fellow Ohioan John Sherman as the party’s presidential candidate for that November’s election. The next time he saw his Mentor farm, Garfield himself was the somewhat surprised Republican presidential nominee, and the farm became his campaign’s headquarters. Even as a candidate for the nation’s highest office, Garfield meticulously tracked the work being done on his farm. On July 31, 1880 he recorded: “Men continued threshing until noon. Had the oats hauled in from the field and threshed as they arrived. Result 475 bushels. Not so good a yield as last year. All spring grain seems to be lighter this year than the fall sown crops.”

Two weeks later, on August 13, he noted, “Have agreed to send my wheat, about 200 bushels of it, to Cleveland for sale at 90 cents per bushel.” On September 19: “Did not attend church, but made a tour over the farm, inspecting the cattle and crops.” On Election Day, November 2: “Arranged for plowing and seeding garden east of house, and starting a new one in rear of engine house.”

Garfield won the election, and from November 1880 to late February 1881, he hosted many visitors seeking an audience with the new President-elect. On January 26, 1881, Garfield recorded in his diary, “Profs. C.D. Wilber and Aughey of Nebraska came at noon, and spent the night…I sat up too late with Wilber for my health.” So just who were these Nebraskans who stopped by to visit and spend the night in the President-elect’s home?

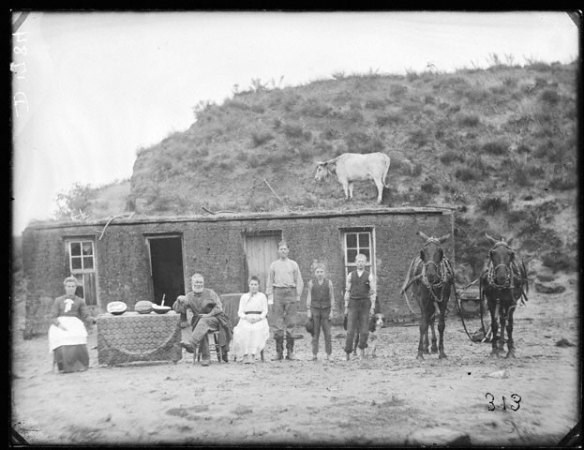

University of Nebraska-Lincoln

Naturalist and geologist Samuel H. Aughey was a faculty member at the University of Nebraska who published widely on the natural features of his adopted state (he was a Pennsylvania native). He was also a shameless booster of settlement on the Great Plains, encouraging homesteaders and other land seekers to settle in Nebraska. During an unusually wet period in 1880, Aughey asserted that prairie sod being broken by plows was the reason for the increased rainfall. It stood to reason, then, that more settlers turning over more acres of soil would lead to ever more rainfall, and drought on the Great Plains would never be a problem as long as farmers continued to plant and harvest crops. The prairie soil would, according to M. Jean Ferrill in Encyclopedia of the Great Plains, “absorb the rain like a huge sponge once the sod had been broken. This moisture would then be slowly given back to the atmosphere by evaporation. Each year, as cultivation extended across the Plains…the moisture and rainfall would also increase until the region was fit for agriculture without irrigation.”

Journalist and author Charles Dana Wilber picked up on Aughey’s theory and included it in his 1881 book The Great Valleys and Prairies of Nebraska and the Northwest. It was Wilber, in fact, who coined and popularized the phrase “rain follows the plow,” which made Aughey’s bizarre theory more easily accessible to the public by breaking it down to a single phrase:

“God speed the plow…. By this wonderful provision, which is only man’s mastery over nature, the clouds are dispensing copious rains … [the plow] is the instrument which separates civilization from savagery; and converts a desert into a farm or garden…. To be more concise, Rain follows the plow.”

Wilber also offered divine allegories for man’s besting of the natural environment in the area once labeled “the Great American Desert”:

“In this miracle of progress, the plow was the unerring prophet, the procuring cause, not by any magic or enchantment, not by incantations or offerings, but instead by the sweat of his face toiling with his hands, man can persuade the heavens to yield their treasures of dew and rain upon the land he has chosen for his dwelling… The raindrop never fails to fall and answer to the imploring power or prayer of labor.”

Nebraska State Historical Society

“Rain follows the plow” fell by the wayside when the Great Plains endured severe droughts in the 1890s that even the steel plows and increasingly mechanized implements of farmers could not prevent. Today, the theory is considered junk science, on par with phrenology, séances, and fad diets. But in January 1881 when they visited President-elect James A. Garfield, Samuel Aughey and Charles Wilber were just entering the period that would make them and their now-discredited theory famous. What fun it might have been to be a fly on the wall and eavesdrop on the conversation on the night of January 26, 1881, when the President-elect “sat up too late with Wilber for my health.”

Written by Todd Arrington, Site Manager, James A. Garfield National Historic Site, April 2013 for the Garfield Observer.