Last updated: January 3, 2021

Article

James A. Garfield and a Black Washingtonian, Part I

Author’s image

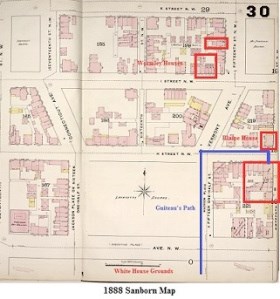

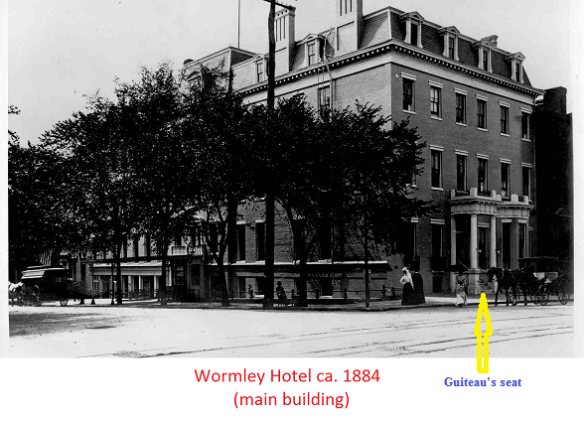

Guiteau following nearby, and after checking the readiness of his gun, took up a vantage point directly across the street by sitting on the front stoop of Wormley’s Hotel. This building was the flagship of African American entrepreneur James Wormley’s renowned hospitality enterprises in Washington.

Author’s image

According to reportage in the New York Herald, Guiteau waited at this location for one half-hour for the President to emerge. Unfortunately for the assassin, the President came out of the house with Secretary Blaine, directly opposite where Guiteau was waiting in ambush. The two men walked arm-in-arm along the same path in the opposite direction taken by the President earlier that evening, returning to the White House. With Secretary Blaine on the left side of the President between the assassin and his target, it seemed that even after days of trailing the President, this would no longer be the optimum time for the attempt. Unfortunately the assassin did not have long to wait and completed his attack on the President the next day, Saturday July 2, at the Baltimore and Ohio railroad depot.

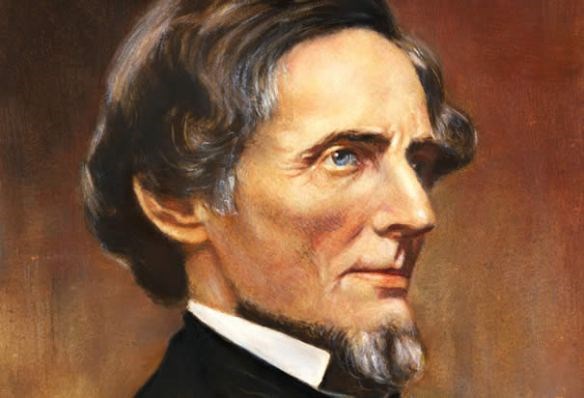

Interestingly, as we begin to report here, this was not the first occasion when the lives of this leader of the United States and his African American business acquaintance became intertwined. James Wormley’s reputation as a nurse, caterer and hotelier had already been widespread, both nationally and internationally, in the decade prior to the Civil War. Beginning with Buchanan’s administration James Wormley, the son of a free Black couple who had arrived in Washington in 1814, had operated a row of boarding houses and his restaurant from his properties on I Street NW between 15th and 16th Streets. This location was just one block to the north of Lafayette Square just beyond St. John’s church (sometimes referred to as the President’s Church). At that time James’s businesses as a restaurateur and hotelier were in addition to his duties as the steward for the Washington Club on Lafayette Square during the 1850s. The patrons of this Club had included men like Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee, Charles Sumner, William Corcoran and some of the most powerful men from both the North and South.

History.com

When General McClellan was living in the Dolley Madison House on Lafayette Square during his tenure as head of the Union Army he was a regular and frequent patron of James’s dining rooms. In a letter to his wife on August 23, 1861 the general told his wife: “We (the general and his staff) take our meals at Wormley’s, a colored gentleman who keeps a reaurant just around the corner on I St.” On November 20 of that year, in an article in the Evening Star, Col. John H. Forney gave a dinner there for about 50 gentlemen including the Secretary of War, several army generals, and John Hay and John Nicholay, the private secretaries to President Lincoln.

Library of Congress

In 1869, after six years of living in Washington as a Congressional representative from Ohio, Garfield and his wife built a house just two blocks east of Wormley’s on I Street at the corner of 13th Street. His Congressional colleagues from Ohio, Americus V. Rice and Frank H. Hurd, would spend some of their years in the city taking up residence at the hotel, additionally leading to the conjecture about the visits to Wormley’s from Garfield. His good friend, former Ohio governor Salmon P. Chase, who was also a customer and friend of Wormley, was named Treasury Secretary by Lincoln. In fact, James Wormley was frequently called upon to cater meals for several Cabinet members such as Gideon Welles, William H. Seward and Edward Bates. James Wormley was so fond of anti-slavery activist Chase that in 1872 he purchased the portrait of then Chief Justice Chase, which had been commissioned by Jay Cooke.

Written by Donet D. Graves, Esq., Volunteer Contributor, James A. Garfield National Historic Site, May 2014 for the Garfield Observer.