Part of a series of articles titled People of the California Trail.

Article

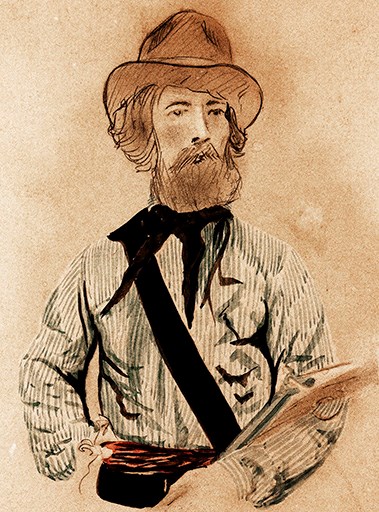

J. Goldsborough Bruff, the California Trail

Image/Public Domain

J. Goldsborough Bruff – California Trail[1]

By Angela Reiniche

To travel o’er the rocky ridge,

And down the rugged mountain side;

To sleep within a jungle hedge,

Or on the grassy prairie wide.

With fire blazing at his feet,

To scare away the panther bold;

To eat, by mountain brook, his meat,

To suffer heat, fatigue, and cold;

These the advent’er’s certain fate,

Who travels o’er, from sea to sea,

Columbia’s continent-estate,

The sea-girt homestead of the free.

- J. Goldsborough Bruff, 1849

After studying something for many years, one might be tempted to experience it firsthand. Take, for instance, the life of Joseph Goldsborough Bruff. Trained as a draftsman and cartographer, Bruff reproduced many, many maps of the West—until he realized there was a more interesting way to put this knowledge to use. Born 2 October 1804 in Washington, D.C., Bruff was the eleventh child born to Thomas Bruff and his wife, Mary Oliver. As Washingtonians, the Bruffs knew surely knew of the Louisiana Purchase—and of the explorers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, sent by President Jefferson to explore it. Lewis and Clark’s trail journals, which included detailed maps, stories of their encounters with Indigenous peoples, and illustrations of western flora and fauna, became an invaluable guide to the adventurers and emigrants that followed them. A little more than forty years later, news of California’s bountiful mineral resources encouraged J. Goldsborough to embark on his own overland journey. Trained as a draftsman and cartographer, Bruff’s sketches, paintings, and written descriptions of his trip, like the journals of the Corps of Discovery, became a useful guide for those who followed. His documentation of the United States’ expansion, of western landscapes, and of everyday life in California’s gold camps contributes generously to the narrative and visual history of the California Trail.[2]

Bruff’s penchant for adventure arrived early in life. His father Thomas, a prominent dentist and inventor, died mysteriously while on a trip to New York when Bruff was just twelve years old. After that, he joined his older brother in school at West Point, where he excelled in math and in earning the admiration of his teachers but was eventually forced to leave the military academy after dueling with a fellow student. His mother had died a year earlier after suffering a prolonged illness. (Official records in Washington, cited by the editors of his journals, argue that his reputation for violence and frequent news of her son’s “misconduct” had hastened his mother’s death.) In 1822, with nowhere to go and “smarting under his disgrace, his blighted career, and always acting upon impulse,” Bruff left West Point. Upon learning that a ship was ready to leave Georgetown for northern Europe, the editors of Bruff’s journals noted that he “embarked on a merchant sailing vessel . . . as a cabin boy, without consulting the remnants of his family.” He spent the next five years travelling as an itinerant seaman, visiting ports throughout Europe and South America.[3]

In 1827, upon his return to the United States, Bruff took a job as a draftsman at the Gosport Navy Yard in Norfolk, Virginia. After a decade of grumbling about his pay, Bruff took his skills to the Army Corps of Topographical Engineers after its authorization by Congress in July 1838. He spent long hours in the painstaking reproduction of the detailed maps that the engineers included with their final field reports.[4] Most significant to the history of U.S. westward expansion and of the California Trail, Bruff reproduced all the maps and drawings included in John C. Frémont’s reports from the Corp’s expedition over the emigrant trail to Oregon and to California from 1842 to 1846; he also copied the surveys William H. Emory made while engaged with Stephen W. Kearny’s Army of the West en route to California in 1846-1847. Because of Bruff’s work, the West was always on his mind in some way or another. Moreover, Bruff began to develop knowledge that would prove useful to someone planning to lead an expedition company of their own.

When reports of California’s mineral resources began filtering into Washington, Bruff once again gave in to his adventurous urges. A fragment of manuscript in his handwriting describes how Bruff came to form the Washington City and California Mining Association in 1849: “Having made duplicate drawings of all of Fremont’s Reports, maps, and plates for the two houses of Congress – it revived the Spirit of adventure So long dorment [sic], and I was anxious to travel over, and see what my friend had so graphically and scientifically realized: more particularly when a golden reward appear’d [sic] to be awaiting us” in California. Although Bruff was married with children, his wanderlust appeared to be winning out.[5]

Bruff wrote that his original plan had been to organize about a dozen men, “a few friends whom I thought might desire to try it also.” Word got around about their first meeting at Apollo Hall and a number of citizens showed up to convince Bruff and his associates to support an emigrating party. Bruff was named chair of the company and, after that, the organizational members met weekly at his home to plan their overland journey. During those gatherings, they drafted a constitution, formed a Committee on Supplies, and “drilled the younger men as light infantry.” Owing to his military affectation, and in keeping with the style of many forty-niner companies, the sixty-six men were “neatly uniformed in grey frock and pants, and felt hats – armed with rifles, muskets, and a few large fowling pieces, all necessary accoutrements, canteens, gum suits and blanket, pair of revolvers in belt, large bowie knives, and belt hatchet – and lots of ammunition.” [6] The Washington City and California Mining Association was well outfitted. As Bruff recalled, “we had a supply of all necessary mechanical tools and appliances: a travelling forge, obtained here from government – and were well-prepared for any emergency that might happen.” The company’s men ranged in age from fifteen to fifty, but the majority were under thirty. Aside from the officers of the company, all of whom were older men, the travelers included an artist, an ensign, twelve carpenters, a blacksmith, and a physician. They procured fourteen wagons and an equal number of tents in Pittsburgh. Others in the same place gathered other necessary provisions and supplies. Another team, who “proceeded far ahead,” secured the seventy mules necessary for the trip. On 31 March 1849, two days before the company started its overland journey, the Tri-Weekly Intelligencer reported that the members of the Washington City and California Mining Association had been chosen for their “talent, enterprise, and respectability.” [7]

On 30 Jan 1849, Bruff wrote to Col. Peter Force that the company had been formed and that they planned to go to California via the Plains and South Pass of the Rocky Mountains. Each member of the company was an equal shareholder and upon arrival, the plan was to select a site for mining, trading, water, health, and protection. The members would share equally the dividends after paying the $300 share that each man owed for the general outfitting of the journey. Bruff informed Force that he would keep a journal while en route and furnish “sketches and meteorological observations to be published as a guide for future travelers.” He wrote that the association planned to operate for approximately ten to eighteen months.[8]

Problems within the company started before they crossed the Missouri River. In April 1849, when they arrived at St. Joseph, Missouri, the line of wagons waiting to use the single ferry to cross the river numbered in the hundreds. Tensions rose as the waiting parties argued about their places in line and led to violent confrontations, some of them fatal.[9] Rather than join the fray, Bruff directed his company toward the old Fort Kearny in present-day Nebraska, along the western side of the Missouri River. The company successfully crossed there, but not without considerable exertion since the river was in flood state. After that, the company journeyed up the Platte River, which Bruff knew was easier than the route between St. Joseph and the new Fort Kearny (west of Grand Island); they would travel on firm ground and only make one crossing at Salt Creek.[10] After passing Fort Laramie in southeastern Wyoming, the journey became more difficult. The landscape was rugged, poorly documented, and—as Bruff knew from his work—filled with numerous paths leading to California. Armed with “all the Maps and works on the country,” Bruff led the company along the Platte and eventually to Fort Hall (in what is now southeastern Idaho).[11] Alongside Frémont’s Report and T.H. Jefferson’s map, Bruff consulted emigrant guides compiled by J. Quinn Thornton, Clayton, Ware, and L.W. Hastings. He knew that roughly that their destination, Sacramento, was still 800 miles away. However, none of his maps or guidebooks prepared the intrepid adventurer for difficulties his company would face when they reached the Sierra Nevada. Knowing somewhat of the dread that most travelers had experienced in crossing the range, Bruff had already made up his mind to make the trek on his own.[12]

Like most who traveled overland to California before the completion of the transcontinental railroads, the men of the Washington City and California Mining Association endured daily monotonous marching and suffered the heat, cold, dust, and storms. They were often anxious about access to water and finding grass for their livestock; more serious hazards, like capsized wagons and cholera, lurked in waiting. Dissent within the company added to the already formidable difficulties of overland travel; Bruff’s compatriots, for example, grew annoyed by his insistence on a round-the-clock guard duty. He later recalled a conversation with Colonel Bonneville when they met at new Fort Kearny. The famed commandant warned Bruff that ahead of him was “a most trying, thankless, and unenviable task …that if with extraordinary patience, forbearance, and determination, [you] succeed in keeping the Company together, to California, [you] shall do wonders.”[13]

He got them all to the eastern foothills of the Sierra Nevada. Most had fared well, reporting “no deaths by Indian attack” and none of the hunger, scurvy, and fevers that plagued so many other parties. However, by this time they were out of provisions and physically worn down. Whatever path they chose to reach the gold fields would be difficult and, by that time, Bruff had fallen ill and could not forge ahead. Temporarily defeated, Bruff turned over his leadership to his second in command and established “Bruff’s Camp” in order to protect the company’s property until they could send for it. He spent a treacherous winter there, starving and cold; the promised help from his company never arrived. Even worse, once the weather warmed and Bruff began exploring California’s gold country, he found no gold worth mentioning. After more than a year of discouragement, he decided to return to Washington, leaving California on a sailing ship in June 1851. About a month later, on 20 July 1851, he wrote from his diary: "At 6 A.M. I breakfasted, and entered the cars for home, and in a little over two hours, was in the bosom of my family, after an absence of two years and three and three months. Never before did I so devoutly appreciate the heart-born ballad, 'Home! Sweet home!' of my departed friend John Howard Payne, and none the less [sic] that I had “seen the elephant” and emphatically realized the meaning of the ancient myth – travelling in search THE GOLDEN FLEECE!"[14]

Bruff was at home again in Washington. He returned to his work for the government in the summer of 1851, this time serving as the Supervising Architect of the Treasury Department. According to federal census records from 1880, Bruff reunited with his wife Elizabeth, sons William and Charles, daughters Zuliema and Celestine, three grandchildren, and an African American domestic servant named Annie Bruce. Zuleima had shared her father’s passion for art and became a painter herself. The family, excepting William, lived at 1009 24th Street, and Bruff continued to work as a draftsman up until the last four months of his life. He died at home on the evening of 14 April 1889 after suffering a short illness.[15] Although Bruff left California in 1851, he continued to visit it vicariously through the numerous works of art he created in the last four decades of his life. Many of those paintings and drawings are held in the Beinicke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University and have been reprinted in more than a dozen contemporary works about art and art history, providing a rare visual and textual perspective on what became known as the California Trail.

[1] Part of a 2016–2018 collaborative project of the National Trails- National Park Service and the University of New Mexico’s Department of History, “Student Experience in National Trails Historic Research: Vignettes Project” [Colorado Plateau Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit (CPCESU), Task Agreement P16AC00957]. This project was formulated to provide trail partners and the general public with useful biographies of less-studied trail figures—particularly African Americans, Hispanics, American Indians, women, and children.

[2] J. Goldsborough Bruff, The Journals, Drawings, and Other Papers of J. Goldsborough Bruff: Captain, Washington City and California Mining Association, 2 April 1849 – 20 July 1851. ed. Georgia Willis Read and Ruth Gaines. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1949), xix.

[3] Ibid, xii–xiii.

[4] Histories of the Army Corps of Engineers include William Goetzmann, Army Exploration in the American West, 1803–1863 (1959, repr., Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1979) and Frank N. Schubert, The Nation Builders: A Sesquicentennial History of the Corps of Topographical Engineers, 1838–1863 (2004).

[5] Bruff, Journals, viii.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid, 32–33.

[9] Ibid, 34; and quoted in The Independence (Mo.) Expositor, 21 April 1849.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] See images from Journals reprinted online at https://www.sierracollege.edu/ejournals/jsnhb/v2n2/Bruff.html.

[13] Bruff, Journals, 49.

[14] Bruff, Journals, part II, 523. (caps in original)

[15] Tenth Census of the United States, 1880. Census Place: Washington, Washington, District of Columbia, District of Columbia; Roll: 122; Page: 258D; Enumeration District: 036 (NARA microfilm publication T9, 1,454 rolls). Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29. National Archives, Washington, D.C.

Last updated: March 7, 2023