Last updated: January 14, 2026

Article

Italian Americans at Faneuil Hall

Boston's spirited Italian community began as the city attracted a steady stream of Italian immigrants in the late 1860s. By 1876, the population grew large enough for them to establish their own Italian Catholic Church, St. Leonard's, which still stands today on Hanover Street. The population stood at around 1,200 people in 1880, growing to over 25,000 by 1905. Primarily emigrating from southern Italy and Sicily, most Italians moved into the concentrated North End community.[1]

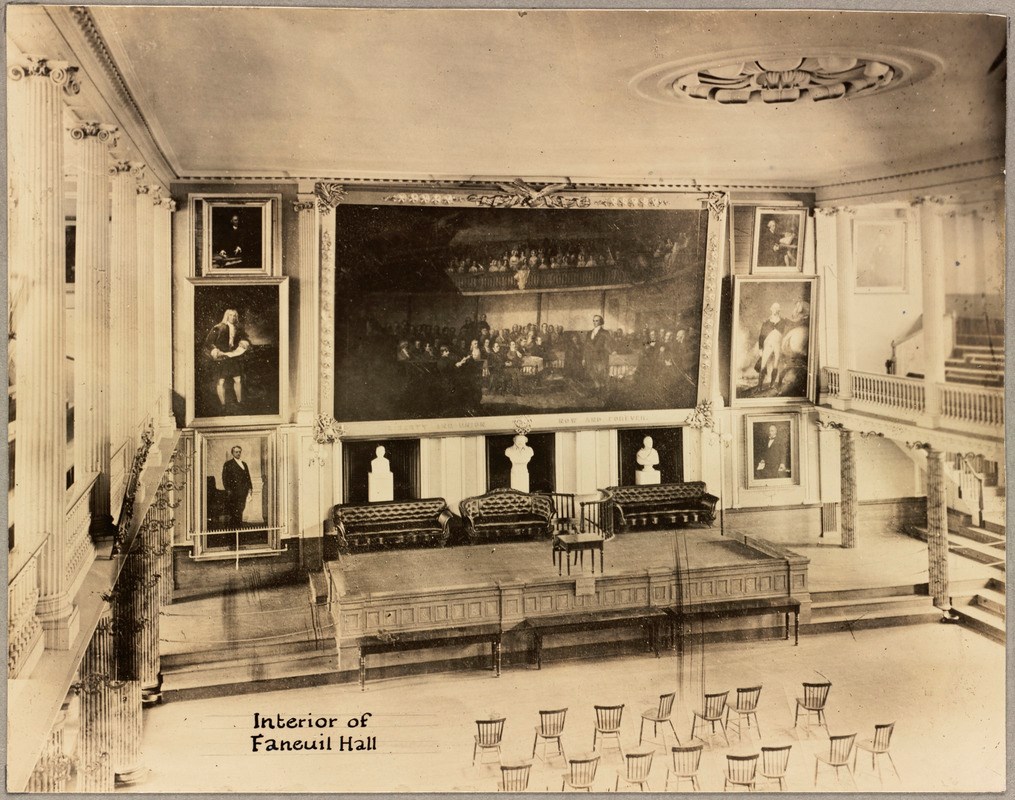

The city's demographics have changed considerably since 1905, but even today the Italian American culture remains in the North End's restaurants and businesses, and the majority of foreign born residents currently living in the neighborhood are Italian.[2] While new to Boston's established communities, Italians in the 1800s and 1900s gathered in the same place Bostonians had convened since 1742: Faneuil Hall. The Great Hall has a way of molding into whatever shape the people of Boston need, and for Italian Americans it became a space to hold mass meetings, mourn prominent deaths, support presidential candidates, and protest injustice.

Early Gatherings at the Hall

One of the earliest gatherings of Italians at Faneuil Hall occurred in 1878, when the small community mourned the death of unified Italy's first king, Victor Emanuel II. Men, women, and children filled the Great Hall as American and Italian flags draped the stage.[3] Four years later the community similarly adorned the Hall for a meeting honoring the life of deceased revolutionary hero Giuseppe Garibaldi.[4] Garibaldi had actually been to Boston in 1853 and, according to Judge Thomas Russell in an 1860 speech, may have even visited Faneuil Hall.[5] Russell spoke at the Garibaldi meeting, and the invited guests included the mayor, the governor, pioneering physician Dr. Mary Safford, and civil rights advocate Wendell Phillips. Both of these early meetings had been organized by the same group of prominent community members, including Pietro Pastene, the co-founder of the Pastene food company, and featured speeches in Italian and English.[6]

c. 1885-1890, Boston Public Library

Responding to Anti-Immigrant Sentiments

Italian American meetings at Faneuil Hall became livelier and more contentious in the following decades as the population grew and anti-immigrant sentiment spread across the country. One of these meetings occurred in the wake of the March 14, 1891 lynching of eleven Italian Americans in New Orleans in retaliation for the murder of police chief David Hennessy. Allegedly, members of the local mafia murdered Hennessy, and authorities arrested a small group of local Italians for the crime. While these men remained jailed, a mob of enraged New Orleanians broke into the prison and shot, clubbed, or hanged eleven of the accused.[7] Both the New York Times and the Boston Globe voiced support for the murderous mob, declaring Hennessy’s death "avenged."[8] Italian Americans across the country (and the Italian government) expressed outrage.[9]

In response to these killings, Boston’s Italian American community gathered first at Roma Hall in the North End where they planned a larger protest in Faneuil Hall.[10] 1,500 people crowded into the Great Hall on March 17 to declare their loyalty to the United States while demanding justice and reparations for those killed.[11] "If the American government does not make reparation-and I am a proud American citizen-I will take my papers of citizenship, go to the market, buy rotten eggs, and break those eggs on those papers!" declared Rocco Vizzari, a North End barber and playwright to cries of "bravo!"[12] Dominic Maggi of Chelsea remarked: "New Orleans is the only [city] that does not know of the existence of Faneuil Hall. If they had read the history of Massachusetts, this bloody outrage would never have occurred."[13]

Despite the outrage, Massachusetts Congressman Henry Cabot Lodge responded with an argument for restricting immigration, published in the North American Review: "Such acts as the killing of these eleven Italians do not spring from nothing without reason or provocation." He confirmed his anti-immigrant views by stating:

Immigration of people removed of us in race and blood is rapidly increasing, and that these people are almost wholly illiterate and for the most part without resources, either in skill, training or money. We also learn that many of them come here merely for a temporary purpose, and that by one channel or another the paupers and criminals of Europe...are pouring into the United States.[14]

Lodge later served in the United States Senate from 1893 until 1924, spending much of his lengthy senate career lobbying for stricter immigration laws and literacy tests for immigrants.[15]

The Bread and Roses Strike

Italian American protests at Faneuil Hall continued into the 1900s.[16] Italian socialists gathered there in the wake of the Lawrence, Massachusetts, Bread and Roses strike of 1912. Two of the strike's organizers, Joseph Ettor and Arturo Giovanetti, had been arrested and imprisoned for the murder of fellow striker Anna LoPizzo, killed during a clash between police and striking factory workers.[17] Italian socialists convened 1,000 men, women, and children in Faneuil Hall on a steaming summer day to protest the arrests of the two organizers, who had been miles away at the time of LoPizzo's death.[18] Organizers of the meeting gave impassioned speeches in Italian to an agitated crowd. While the meeting ended without incident, a brawl ensued as people began filing down the stairs to exit. The next day's Boston Globe described the scene:

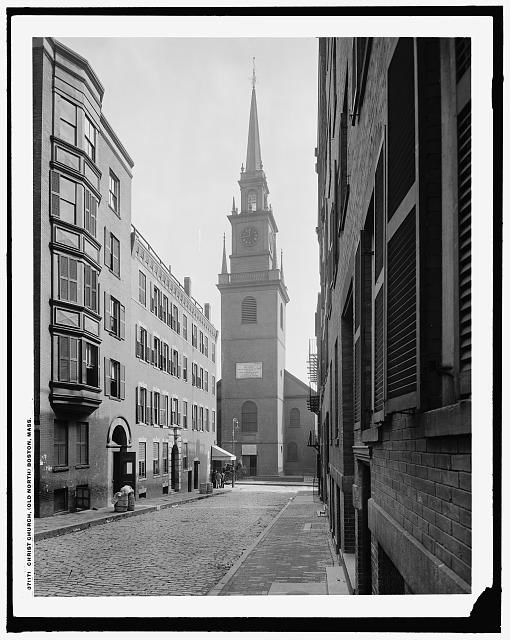

Library of Congress

Revolvers and knives were drawn, one shot was fired, several policemen were injured, several men in the crowd were also injured and one man was arrested in Faneuil Hall last evening at the conclusion of an Italian Socialist mass-meeting...There was a wild fight in the hall for about ten minutes.[19]

The brawl began when twenty-six year old North End resident Fernando Carabeli lit a cigar as he exited the Hall. One of the police officers ordered him to extinguish it and shoved him toward the door. Carabeli shoved back and told the officer he was "no dog," to which the policeman responded by beating Carabeli with his club. The commotion caused the remaining crowd and those who had just exited to rush the officers, shouting and throwing chairs at them. One of the officers clubbed his way through the mass of people. As he reached the center, someone in the crowd fired a revolver, possibly the first time a gun had ever been fired in the Great Hall. The sound caused the crowd to scatter. Although no one had been injured by the gunshot, the officers arrested Carabeli for inciting a riot.

In Carabeli's sentencing, the municipal court judge adopted anti-Italian and anti-labor sentiments, stating that he did not approve of Faneuil Hall "being let for meetings of such a character" and argued that the speeches had inflamed the crowd and not the cigar incident. He sentenced Carabeli to one year in prison and three accused accomplices to six months.[20]

From Wartime to Sacco and Vanzetti

Anti-immigrant sentiment followed even patriotic meetings. In 1917, a parade of 5,000 Italian Americans marched through the North End to support President Wilson after Congress declared war on the Central Powers, officially entering the First World War. The parade flew American and Italian flags, and the bands played the "Star Spangled Banner." Eventually the parade made its way to Faneuil Hall, where the caretaker of the Hall barred them from entry because their American flag had been lost, leaving only the flag of Italy.

After procuring an American flag, 1,500 were allowed in the Hall before the police locked the doors, leaving the remaining 3,500 outside. Those left outside began banging on the doors and windows, demanding entry, until finally some of the speakers made their way to the steps of Quincy Market to address the crowd from there. Due to the chaos and anti-immigrant demonstrations of the events prior to the meeting, the speeches from several state politicians focused on reminding those in attendance that though they may love their motherland, their first allegiance must be to the United States.[21]

Italian immigration declined significantly after Congress passed the Immigration Act of 1924, fulfilling Henry Cabot Lodge's goal of restricting immigration.[22] While Italian Americans began to assimilate more into American culture, the Boston community continued to hold meetings at Faneuil Hall. Italian American women, newly enfranchised, gathered in 1920 to pledge support for the Republican ticket.[23]

Meetings held in 1923 and 1925 supported Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, two Italian anarchists charged with a Braintree murder that eventually resulted in their executions.[24] After these two Faneuil Hall meetings the city denied further use of the hall for Sacco and Vanzetti defense meetings due to their controversial support of anarchism.[25]

Boston City Archives

Mid-1900s to Today

In the following decades, Italian Americans began to gain political power in Massachusetts and meetings at Faneuil Hall declined. In 1957, the state elected its first Italian American governor, Foster Furcolo, and then elected its second, John Volpe, to succeed Furcolo in 1961.

In January 1994, just over one hundred years after the outrage and demand for reparations over the lynching in New Orleans, Thomas Menino delivered an inaugural address at Faneuil Hall as the first Italian American mayor of Boston. Menino held this position for twenty years, the longest tenure in the city’s history. In recognition of his two decades of service to the city, Mayor Menino's body lay in state at Faneuil Hall after his death in 2014.[26] In their use of Faneuil Hall over the last 140 or so years, Italian Americans truly integrated themselves into the fabric of the Boston community.

Footnotes

[1] Stephen Puleo, Boston Italians (Boston: Beacon Press, 2007), xi, 7-9.

[2] Leventhal Map Center, “Boston neighborhoods : top 10 countries of birth for foreign-born population.” Accessed November 3, 2019 https://collections.leventhalmap.org/search/commonwealth:h989r707c

[3] “Il Re Galantuomo,” Boston Globe, January 18, 1878, 5.

[4] “Boston Italians,” Boston Globe, June 16, 1882, 2.

[5] Documents of the City of Boston. United States: n.p., 1861, 54.

[6] Documents of the City of Boston. United States: n.p., 1861, 54.

[7] “Chief Hennesy Avenged,” New York Times, March 15, 1891, 1.

[8] “Chief Hennesy Avenged,” New York Times, March 15, 1891, 1; “Avenged! Mob Rules Supreme in New Orleans,” Boston Globe, March 15, 1891, 1.

[9] “Question for Diplomacy,” Boston Globe, March 16, 1891, 6.

[10] “EXPATRIATED!” Boston Globe, March 17, 1891, 1.

[11] “Bade Be Calm” Boston Globe, March 18, 1891, 3.

[12] City of Boston Reports of proceedings of the City Council of Boston (Boston: Rockwell and Churchill City Printers, 1897), 29; “Gaiety and Bijou,” Boston Globe, June 14, 1891, 11; “Bade Be Calm,” Boston Globe, March 18, 1891, 3.

[13] “Big Open Air Meeting,” Boston Globe, October 30, 1896, 3; “Bade Be Calm,” Boston Globe, March 18, 1891, 3.

[14] Henry Cabot Lodge, "Lynch Law and Unrestricted Immigration," The North American Review 152, no. 414 (1891): 602-11. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25102181

[15] Henry Cabot Lodge, “The Restriction of Immigration,” Speech Before the U.S. Senate, March 16, 1896.

[16] “Abuses Many,” Boston Globe, June 1, 1894, 6.

[17] James P. Heaton, “The Legal Aftermath of the Lawrence Strike,” The Survey, September 1912, 503.

[18] “Sentenced For Inciting Riot,” Boston Globe, July 9, 1912, 14.

[19] “At Bay by Weapons,” Boston Globe, July 8, 1912, 1.

[20] “Sentenced For Inciting Riot,” Boston Globe, July 9, 1912, 14.

[21] “Italians Shout For US at Faneuil Hall,” Boston Post, April 16, 1917, 14.

[22] “‘Immigration Act of 1924,’” Library of Congress, n.d., accessed October 16, 2020.

[23] “Will Support G.O.P. Ticket,” Boston Post, October 8, 1920, 32.

[24] “Cotillio Tells Why He Came to Help,” Boston Globe, June 23, 1923; “Moriarty Attacks Police Superiors,” Boston Globe, March 2, 1925.

[25] “Sacco Group Urges Semi-Public Meeting,” Boston Globe, May 27, 1927.

[26] “Thomas A. Menino, Boston’s Longest Serving Mayor, Dies at 71,” Boston Globe, October 31, 2014.