Last updated: September 17, 2024

Article

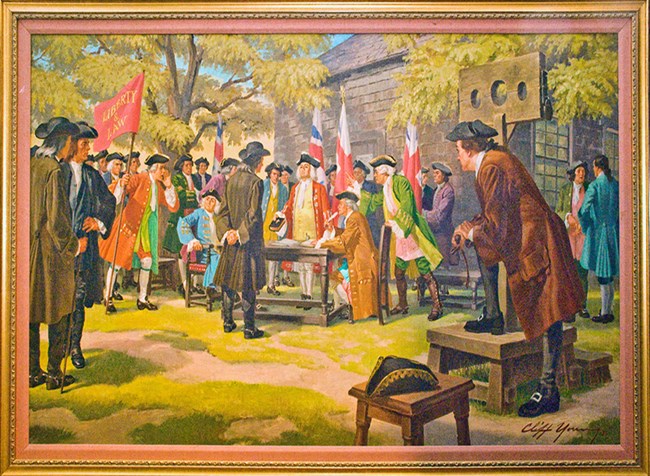

Intrigue on the Village Green: The Election of 1733 at St. Paul's

(Text of an exhibition that was on display in the visitors' center museum, at St. Pauls' Church N.H.S., from Feburary 2015 through January 2017.)

It must have been quite a scene on an open field at the center of a small, quiet colonial town, usually occupied by a few farm animals and a handful of crude grave markers clustered behind a modest wooden meetinghouse. On Monday morning, October 29, 1733, the political tension of the colony of New York suddenly descended on the town common of Eastchester, the parish of St. Paul’s Church, about 20 miles north of New York City.

More than 400 men marched onto the Village Green in two separate columns, each led by horse-mounted riders, their entrance announced by the blaring sounds of trumpets and violins. These scores of New York colonists separated into two camps, facing each other across an open space, waiting for the sheriff to arrive. This extraordinary spectacle was the result of a dynamic confluence of circumstances: a serious battle for political power between the Royal Governor and an opposition party, the founding of an insurgent newspaper, and a special election for a countywide seat in the New York assembly. These conditions led to the Great Election of 1733 on the Green just outside this building, which laid the foundation for a confrontation over freedom of conscience and voting rights.

One of the most surprising things about the election is that we know about it. For perhaps the first time in American history, there was eyewitness coverage of a seriously contested election which drew a large turnout. A multi-paragraph, descriptive article of the event appeared in the inaugural issue of The New York Weekly Journal.

That piece remains one of our earliest windows into the political lives of the colonists, documenting a great public drama that showcased the pageantry of participatory democracy, as practiced by early Americans. It also captured the political manifestations of religious discrimination and electoral intrigues of an earlier time. The victory of the candidate opposed to the Royal Governor heralded a continued battle for political influence in New York. The account in the newspaper presaged a milestone in the advancement of religious freedom, illustrating the influence of an independent press.

We invite you to explore the many and varied elements of the story of the Great Election of 1733 at St. Paul’s through the artwork, text, documents, artifacts and sound in this exhibition, which was made possible by:

The National Park Service/Department of the Interior

The New York Council for the Humanities

Society of the National Shrine of the Bill of Rights

John and Jean Heins

Prologue: New York in the 1730s

By the 1730s, New York had been a British colony for nearly 70 years, symbolized by the Royal Governor, the crown’s representative and the highest officer in the province. A growing colony with an expanding economy of agriculture, fur trading, and commerce, New York’s population was almost 50,000, an increase of 30-percent from 1720. It was a religiously and ethnically diverse province compared with the other British mainland colonies. Approximately 15-percent of New York’s residents were enslaved Africans. Most of the settlers lived in New York City, Staten Island, Long Island, and the counties bordering the Hudson River. With about 6,000 people, Westchester was the colony’s fifth most populous county.

Rival wealthy families led alliances that dominated New York’s politics, reflected most clearly in alignments in the assembly, whose members were chosen by qualified voters. In part, these factions operated as contenders for political influence, led by wealthy men, supporting legislation that advanced their interests and enhanced relations with the incumbent Royal Governor. But there were consistent differences in outlooks and goals. The Morris family party, or the Country party, sought protection for small farmers, artisans, and shopkeepers, and advocated toleration for dissenting religious denominations, particularly in Westchester County, where the Church of England, or Anglican Church, was the established, official church. The Phillipse family bloc more clearly represented major landowners, wealthy merchants, and the interests of the Anglican Church.

Looking back from our contemporary understanding of voting rights, the elective franchise in colonial America seems cruelly unfair and limited. To qualify in most jurisdictions’ voters had to own land and improvements valued at 40 pounds, extending the suffrage requirement used in England. In the rural setting of Westchester County, that translated into a farm of about 70 acres. Additional age, gender, religious and racial barriers to the ballot led to a restricted participation in the colony’s political life, typical of the time.

Colonists recognized the protection of life and property as the primary function of government, and believed that the stakeholders, or property owners, should be the citizens exercising political choices and selecting leaders. But in a colony where, relative to England, a surprisingly high number (maybe 50-percent) of adult white males owned enough property, or qualified through other means, there was an active political life. The rigor of enforcing the property qualification could vary widely, probably enlarging the pool of participants. A unit of the mighty British Empire, New York’s politics followed the contours of English public life, but often hinged on local circumstances. This experience was reflected in the election of 1733, when models and language borrowed from the opposition in Britain were employed to articulate the struggles between the Royal Governor William Cosby and his challengers.

The Opposition Emerges: Origins of the Cosby/Morris dispute

A major character in this story, William Cosby emerges from the dust bins of history as perhaps a caricature of the meddling royal governor with a narrow vision of personal interests. He reached New York in 1732, achieving the colony’s highest office through patronage and family connections, not uncommon avenues to political office in the 18th century. Cosby’s wife was the first cousin of the Duke of Newcastle, the chief colonial minister. A former soldier, Cosby had suffered financial setbacks in his previous post as Governor of the British possession of Minorca, and he was probably seeking to regain his wealth through the New York governorship. Based at Fort George in New York City, this was among the most lucrative posts in colonial America, with a high fixed salary and many opportunities for additional income.

Upon arrival, Cosby attempted to recover half of the salary earned by Rip Van Dam, a political leader of Dutch ancestry who served as acting governor in the period between Cosby’s appointment and his arrival in New York to assume the duties. Van Dam’s refusal to pay led Cosby to file a lawsuit seeking the share of salary. The governor filed the legal action with the colony’s Supreme Court, a three-judge panel whose members served at the pleasure of the Governor, a likely friendly tribunal. He called upon them to convene as a court of exchequer, an English tradition of specialty courts constituted to rule on revenue matters. While this strategy seemed like an adroit move, it provided a contentious introduction for Cosby to Chief Justice Lewis Morris of Westchester County, an experienced public official accustomed to exercising power and to good relations with royal governors.

The chief justice dismissed the case and wrote a lengthy opinion warning of the constitutional dangers of courts of exchequer. He also lectured his younger colleagues on the court -- Stephen DeLancey and Adolph Phillipse -- about the perils of circumventing normal legal processes. Significantly, Van Dam’s lawyers, James Alexander and William Smith, would soon join Morris in the opposition party. One of their first acts as a group was to commission a young German immigrant printer named John Peter Zenger to publish Morris’s opinion as a pamphlet. In a rare display of good judgment, Governor Cosby wisely chose not to appeal the decision, but he could not countenance Morris’s brazen act of confrontation. In the spring of 1733, he dismissed the chief justice from the colony’s Supreme Court and drew closer to the Phillipse faction in New York politics.

Rather than annoying the wealthy, 52-year-old Westchester County landowner, the dismissal galvanized Morris and freed him from the restraints of his post, allowing him to raise the banner of opposition with alacrity.

The Political Landscape Takes Shape: The Opposition and the Loyal Forces of Governor Cosby

Following the dismissal as chief justice, Lewis Morris, with the energy of a young insurgent, gathered an opposition force, drawing on his family connections and a network of small farmers and trade groups cultivated in many years as a political leader. The emerging political dispute overlapped with a growth in rates of literacy and expanded printing capacity, facilitating a novel employment of campaign broadsides and pamphlets. The Morris bloc even introduced outdoor political rallies in New York City, a more densely populated urban setting which permitted voting on a broader basis than in rural counties. These circumstances yielded one of New York’s earliest independent political opposition drives. Of course, the Royal Governor still enjoyed a tremendous advantage of a tradition and patronage-fueled system of support.

The resistance to Governor Cosby utilized a relatively new set of ideas that had gained legitimacy in England as the justification for the political opposition, known as the Whigs, to the powerful government of Prime Minister Robert Walpole, much of which came through Cato’s Letters. These were enormously influential essays by a pair of British writers, John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon, published in the early 1720s. Widely available and referenced in the colonies, Cato’s Letters expressed an enduring statement of dissenting thought --- the natural equality of men, liberty and, most importantly for our discussion, a “commitment to the natural equality of men who secured their rights and interests through the establishments of government, which was validated thereafter through the expression of electoral will.”

Here was an acceptable forum of ideas for an opposition, drawn from the mother country, which raised the dispute between Governor Cosby and the Morris group to the level of constitutional principle. Also useful was the concept borrowed from Cato’s Letters of Court and Country parties creating a recognizable view of political confrontation, which accommodated the approach of the Morris party. An important manifestation of this emerging strength of the opposition was the establishment of a party newspaper, The New York Weekly Journal; John P. Zenger was hired as the printer. While there had been earlier efforts to print insurgent papers, they were short-lived and largely unsuccessful. But the New York Weekly Journal was a different kind of paper. Well-funded and intelligently edited, it was launched as a clarion organ, the party press, to give voice to the opposition to the Royal Governor. In the context of New York, it was perhaps the most historically significant development of the period. While Zenger prepared his presses, political circumstances created a drama that would unfold on the Eastchester village green. The assemblyman for Westchester County, William Willett, a friend of Morris, died, creating the need for a special election for the vacant seat.

This void encouraged a competitive election between the factions, providing former Chief Justice Morris with the opportunity to reclaim a public position from which he could carry on more active opposition to the governor. The governor’s faction, in co-operation with the Phillipse group, understood the importance of the canvass. They selected as a standard-bearer William Forrester, a teacher in a local church-supported school. To enhance Forster’s credentials, shortly before the election Governor Cosby appointed the teacher to the prestigious post of Westchester County Clerk.

Election on the Green

Something very important was a stake in the election on Monday morning, October 29, 1733, which helped produce the extraordinary turnout. The setting for the public gathering, the Eastchester town common, was centrally located. Four major roads---the Boston Post Road, the road to Westchester Square, the road to Mile Square, the road to White Plains---converged on the Green, facilitating participation by interested voters from all sections of the county. The date also contributed to the large turnout. While evenings might be cool by late October, there was little threat of especially inclement weather, and, most importantly, the harvest had just ended. This was, after all, an agricultural world with a voting base of farmers, who might require several days to participate in the decision on the next countywide assemblyman.

Most of the electors for Forrester came through the established landlord connections of the manors of Westchester along the Hudson River. Tenant farmers who had made sufficient improvements to their land granted on long-term leases qualified as freeholders and were eligible to vote. The Phillipse faction organized a caravan of many of those men to the election site.

Voters favoring the Country party were galvanized through an impressive apparatus financed through Morris’s considerable wealth. Freely distributing food and drink, agents in the party of the deposed Chief Justice led a procession of men reaching Eastchester by traveling south on the Post Road from northern reaches of Westchester through the sections of the county bordering on Long Island Sound. These efforts supplemented and invigorated Morris existing popularity. Political appeals emphasized the interference of royal authority, in this case Governor Cosby, with the popular base of representation by handpicking a candidate and boosting his credentials. These ideas would have engaged colonists whose political heritage recalled British monarchs in the 17th century encroaching on the prerogatives of Parliament. Similar to calling out the militia or marching to a religious revival, the party gathered strength as it marched through the towns. Men joined the procession in Mamaroneck, New Rochelle and Pelham, before meeting Morris supporters from the lower end of the county at the Eastchester green.

So, there they assembled, approximately 420 voters and dozens of curious onlookers, and it must have been quite a spectacle for a small colonial town, whose total population was only about 400. Each side demonstrated their strength, parading around the Green. The Morris side’s campaign reflected themes borrowed from the English opposition. They were led by

two Trumpeters and 3 violines; next 4 of the principal Freeholders, one of which carried a Banner, on one Side of which was affixed in gold Capitals, KING GEORGE, and on the other, in like golden Capitals, LIBERTY & LAW; next followed the Candidate Lewis Morris Efq; late Chief Justice of this Province; then two Colours; and at sun rifing they entered upon the Green of Eaftcehfter the Place of Election, followed by about 300 Horfe of the principal Freeholders of the County, (a greater Number than had ever appeared for one Man since the Settlement of that County;) After having rode three Times around the Green, they went to the Houfes of Joseph Fowler and – Child who were well prepared for their Reception, and the late Chief Juftice, on his alighting by feveral Gentleman, who came there to give their Votes for him.

The superior organizational strength of the Morris opposition was evident in his clear majority of electors on the Green that morning, who lined up near the small wooden meetinghouse at the northwestern side of the field, facing the clustered Forster supporters across the common. But there was too much at stake to simply acknowledge the principle of larger numbers, and the Forrester candidacy had the support of Nicholas Cooper, the sheriff supervising the canvass, appointed by Governor Cosby. Cooper altered a common procedure of simply declaring a winner based on a recognizable superiority of voters lined up behind a candidate. Instead, at the urging of the Forrester voters, the sheriff ordered a formal poll, requiring the men to take an oath on the Bible attesting to the property qualification.

Sometimes used, this procedure was designed to exclude the voters who were Quakers, a Christian denomination who were controversial in England and the colonies for their religious views and behavior. These views included a refusal to take Biblical oaths, claiming the unwarranted questioning of an individual’s integrity had no sanction in the scriptures. A visibly recognizable group of men based on simple dress and wide brimmed hats, they were overwhelmingly represented on the Morris side of the Green.

On other occasions, Quakers had been permitted to affirm, rather than swear on the Bible, an option Sheriff Cooper denied them that day, perhaps unaware that documentation of the practice could cause a political embarrassment. As a result, 37 Quakers were excluded, or disenfranchised. Other qualified electors who accepted the requirement of the Biblical oath stepped forward and publicly announced their preferences. Even without the Quaker supporters, Morris won a comfortable victory, 231-151, in the final tally. Perhaps recognizing that the election was part of a larger political struggle, the affair ended amiably, with the traditional congratulations offered all around. Escorted back to New York City, Morris was greeted with a hero’s welcome.

Epilogue: Groundbreaking Journalism and Freedom of Conscience

A multi-paragraph, descriptive account of the canvass appeared in the inaugural issue of the New York Weekly Journal on November 5. Written by one of the Morris supporters, most likely James Alexander, the article is perhaps the earliest, surviving account of the political culture of the colonists. A leader of the Morris party, Alexander’s review did not correspond to modern expectations of objective, nonpartisan journalism. Yet, the unprecedented report on the early 18th century electoral process remains an important source for scholars of colonial political history.

Lewis Morris emerged from his electoral triumph as a re-awakened political leader. Victor in the Eastchester assembly election, he utilized his elected public office as a platform to continue his campaign to confront Cosby, who he famously referred to as “a God damn ye.” The campaign included gathering signatures on a petition seeking the governor’s recall. The former Chief Justice, and now assemblyman, sailed for London and attempted to meet with Royal officials to present his case for Cosby’s removal. But the effort proved frustrating and futile, caused by bureaucratic subterfuge and the quiet understanding among the King’s ministers that a colonial had little business interfering with Royal administration.

In addition, the report on the crude strategy to deprive Quakers of the franchise generated enough outcry that the Friends petitioned the colonial authorities for redress. In 1734 the New York assembly granted the Quakers the right to affirm (rather than swear) an oath when necessary for participation in the political life of the colony. This law extended a privilege often respected in England, but it registered a milestone in the development of religious freedom in America.

The election and the coverage were also a foundation for a continued battle between the governor and the opposition centered eventually on the New York Weekly Journal. This political and legal dispute culminated in the arrest in November 1734 of the printer John Zenger on charges of seditious libel. His famous acquittal in an April 1735 trial at what is today Federal Hall in lower Manhattan remains a symbol of an emerging acceptance of the role of a free press in early America, and a landmark legal case in American history.