Last updated: April 7, 2025

Article

Interpreting the Cultural Landscape of the Rinconcito de Esperanza and the Surrounding Neighborhood

National Center for Preservation Technology and Training

This presentation, transcript, and video are of the Texas Cultural Landscape Symposium, February 23-26, Waco, TX. Watch a non-audio described version of this presentation on YouTube.

National Park Service

Dr. Sarah Gould: Thank you for having me here today. This is not really my area, so I'm honored to be here with you. I'm going to be talking about a site where I work and I think it does really connect to the earlier panel about managing change so, this is sort of a managing change project as well as an engaging community project.

So, this is the Rinconcito de Esperanza, the "little corner of hope." It consists of 11 small structures on two adjacent lots at 812 and 816 South Colorado Street in San Antonio's historically majority working class Mexican-American Westside neighborhood. It's representative of the once, very dense, massing prevalent on the Westside. The extent lots formerly included 808, 812, 816, 818, 820, 822 and, 824 if you can believe that from here to here. The Esperanza Peace and Justice Center, which is the mother organization of the Museo Del Westside, purchased the central portion, this yellow house, in 2001 to serve as the base for their Artes Vida Westside Cultural Project. By 2007 they bought the southern lot here, with this building right here, which was formerly called Reuben's Ice house, a neighborhood ice house.

Dr. Sarah Gould, Esperanza Peace & Justice Center

The following year, in 2008, through some visioning sessions with the community, the community identified a desire to transform that building into a museum and, just sort of spoiler alert, 10 years went by and then in 2018, they hired me to make that happen. So, we acquired the northernmost lot, these two little houses here as well as five more that are behind it that you can't see, we acquired those in 2017. Basically, one day a for sale sign appeared in front of those houses and, even though it wasn't really in our plan, we were very worried that they would be purchased by a flipper and demolished and so, we just bought them. They are now going to be rehabbed and incorporated into the Rinconcito and be part of the Museo complex.

The Rinconcito is a visible reminder of an earlier era when working class families built multiple small homes on a single lot in order to make ends meet. While just 20 years ago this massing could be seen all along the 800 block of south Colorado. Today we are surrounded by vacant lots, cleared by land speculators.

Dr. Sarah Gould, Esperanza Peace & Justice Center

Behind the property, what you can't see on that photo, is a new structure that we built. So, the majority of the structures at Rinconcito, date from the turn of the century to the 1930s and, yet this one we built in 2017. We built it out of a compressed earth block or adobe, to represent the history of adobe in San Antonio. So, San Antonio's Westside, used to have a lot of adobe and basically it was regulated out of existence. So, when we built this, it was the first commercial adobe structure to be built in the Westside in a century. It houses our MujerArtes Clay Cooperative which, since 1995 has offered training in clay arts to working class women of all ages through sculpting, drawing, painting, and the telling of their stories. Their clay creations reflect the lives of the women as Americana, as Chicana, as Latinas and, as Westside residents.

One thing I want to point out about our buildings at the Rinconcito is that, for the most part they do embody the key aspects of what cultural geographer, Dan Arreola has defined as the principle elements of the Mexican American housescapes. So, that some the fence enclosing the property, the vivid exterior colors and, the yard shrines. We're actually a little low on yard shrine so, I'm hoping we can get some more.

Dr. Sarah Gould, Esperanza Peace & Justice Center

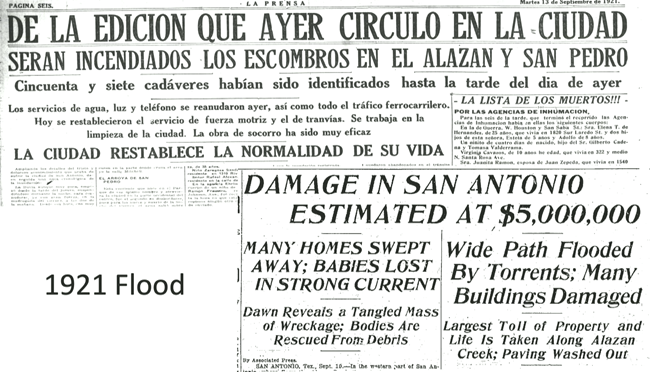

But again, I just want to talk about the density for a minute because it's a recurring story here. But the density there, very common to the period of major growth in the Westside, which is like them starting in the twenties and thirties and, that has to do with the Mexican Revolution. Before we get into the density issue, I do just want to talk about one of the defining moments in San Antonio's history as well as Westside history. Next year will be the Centennial so, this is a major piece of the research that I'm working on right now. But, in 1921 there was a huge flood in San Antonio and these are different representations from newspapers, one from LA Prensa, the Spanish-language paper and one from the Light on English-language paper.

One of the things that, if you're from San Antonio, you've probably heard of a 1921 flood and probably the most dominant images of the '21 flood are these very dramatic photos of downtown buildings with water up to chest height, people standing on the balconies of second floor buildings downtown pointing out the water, that sort of thing. So economically, downtown took a hit from that flood but, I know right there it says 57 cadavers, but I actually think it was 52. But 49 of the 52 people who died in the flood, were Westside residents and, they lived right along the Alazan Creek, which is in the Westside. So, the images are very dramatic downtown, but the real loss was on the Westside.

Dr. Sarah Gould, Esperanza Peace & Justice Center

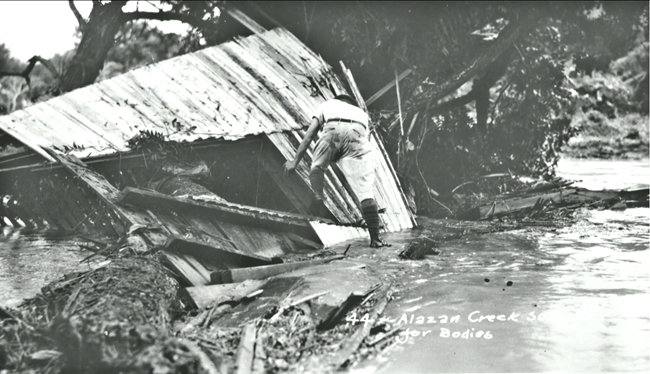

Within days of this flood, the city announced that they were going to build a dam so that this kind of flood would never happen again. That's the Almost Dam, if you're familiar with it. That damn prevented that kind of flooding from hitting downtown again, it did nothing for the Westside. This is the kind of photo that I think of when, I think of the 1921 flood. This is a man looking for bodies along the Alazan Creek, where people's homes were literally just washed away.

In the aftermath of the flood and the loss of lives and the loss of housing, thousands of people were homeless on the Westside after the flood, there became a movement, and this was a national movement, but certainly in San Antonio it was a very big movement, to build public housing so, that's where I'm taking your next. This is going to be a video and it's timed, so I have to talk real fast.

This is Ruben's Ice House, a historic structure that will be the permanent home of our Museo Del Westside, a community participatory museum in one of the poorest but also, most historic neighborhoods of San Antonio. It's a project of the Esperanza Peace and Justice Center and will be the only museum in the Westside as well as San Antonio, that focuses on stories of the working class and the working poor.

Dr. Sarah Gould, Esperanza Peace & Justice Center

We are located in the Westside, which we're slowly zooming into right now, which was an area that, unlike other parts of the city, never had racial deed restrictions and so it was always very racially diverse. But, when the Mexican Revolution broke out, thousands of Mexican refugees arrived making it the heart of Mexican American, San Antonio. While we lack in financial capital, our community is immensely rich in history and culture. Our vernacular architecture, religious sites and our plentiful murals, along with our reputation for producing numerous influential Mexican-Americans, ranging from visual and performing artists to leaders in education, politics and business, has resulted in the Westside being described as the Mexican-American cultural capital of the United States.

However, the Westside experienced a horrific housing shortage in the 1930s during the great depression and of course after the big flood. So, a local Catholic priest and a Jewish architect set out to convince the federal and local authorities to step in and authorize the first public housing in San Antonio. Influenced by the worker housing in Balbuena, Mexico City, the Alazan-Apache Courts also called Los Courts, replaced hundreds of makeshift, one or two room, wooden structures and, provided critical housing for nearly 5000 Mexican-Americans in 1180 units when they finally opened between 1940 and 1941.

Dr. Sarah Gould, Latinos in Heritage Conservation

Today, despite the fact that the city has more than thirty thousand people on a waiting list for public housing, and the fact that this public housing development has been reduced unit by unit to 1800 residents in 685 units, the housing authority has recently announced that this will be demolished. The Alazan Courts are two blocks north of the Museo del Westside and about four blocks from San Antonio's booming downtown. So, we've purchased some of these older homes around the Museo site to preserve the traditional built environment of the Westside. Meanwhile, all around us, developers have purchased and demolished dozens of small houses to make vacant lots, like this one, to sell to bigger developers, to build bigger buildings, not meant for us. We all know change is coming. This is the building in the course of being demolished.

The residents of the Alazan, seen here, are key members of the community we serve. In fact, the president of the Alazan-Apache Courts Resident Association is on our board. Residents of Los Courts have been integral to the culture of the Westside for eighty years. The current residents of Los Courts have no way of knowing where they will end up or how they will maintain their social networks once their homes are demolished.

Adam Castillo

As a community participatory museum, the Museo Del Westside cannot exist without our community. We are worried, not only for the loss of homes, for the residents of Los Courts, but also for the loss of community members for our entire neighborhood. What will the Museo look like without these community members? We have a responsibility to stand with them as they face an uncertain future, and it's also our uncertain future.

So, we recognize that landscapes change. What we are wanting to do is, as part of this change that is coming to this community, is to launch a community storytelling initiative. So, we have a longstanding oral history program at the Esperanza. So, the idea here is to do a storytelling initiative with the residents of Los Courts, starting with oral history, photography and community mapping workshops, so that the residents can share in their own words and through their own eyes, how they feel and think about life at Los Courts and the changes that are coming as well as, what their hopes are for the future. Through this initiative, we will document the lives of Los Courts residents and then work with them to create a public presentation of those stories in a medium of their choosing.

So, this might be an exhibition or a book. It might be a series of radio broadcasts. We have a low power radio station. It could be the production of a play based on their stories. We want to create something with a permanent component that will last another eighty plus years so that their experiences are not lost and so that we can learn from what was done to the residents of Los Courts. This will be an opportunity to empower the community through personal storytelling, while also working towards our goal to not only embrace our role as community advocates, but also to work with our community to build a more equitable future.

Dr. Sarah Gould, Latinos in Heritage Conservation

The residents of Los Courts have already let it be known, that they are not idly sitting by while the housing authority makes decisions about their futures. In the wake of these plans to demolish the Alazan Courts, we saw evictions of Courts residents rise. They increased three fold since 2010 as of last fall. Residents facing eviction for maintenance issues or unpaid fees, they feel like they have no other option than to go public, and these are some of the residents having a public meeting about the evictions. We hope to channel this willingness to go public with their stories into group storytelling such as, our monthly oral history gatherings, where we share stories in a group setting.

We've previously collaborated with the musician, Lorde [ ], to transform some of these oral histories into songs and into a book so, that's another idea for this project to turn it into something musical. Also on our site, as I mentioned, we have the MujerArtes Clay Cooperative, and they do a lot of clay making that tells personal stories. So, we have also been thinking about doing something like that, those are women at the clay cooperative.

We believe the power of storytelling can transform lives and we hope to launch this storytelling program with the residents of the Courts later this year to confront their impending removal due to gentrification and give them the space to share their lives again in their own words and through their own eyes.

Dr. Sarah Gould, Esperanza Peace & Justice Center

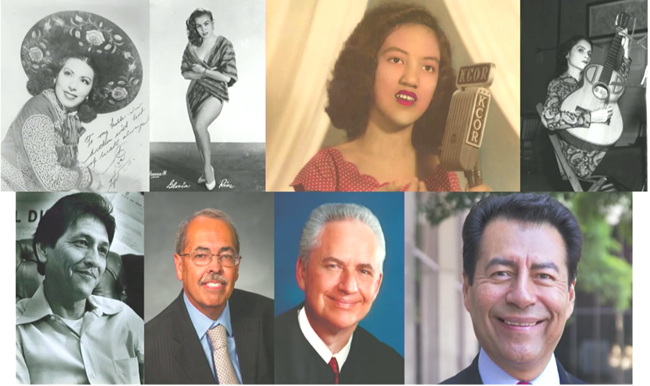

I always am a little hesitant to show things like this because, I think that it maybe inadvertently discounts just regular folks. But I also understand that this is a category on the national register so, these are some celebrities who came out of the Courts. Up at the top there, we've got Eva Garza, internationally known musician, Gloria Rios, queen of Rock-N-Roll in Mexico. Blanca Rodriguez, who just last year, was named a National Heritage Fellow in Washington, D.C., Lydia Mendoza, who also was a National Medal of the Arts recipient and also appears on a US postage stamp. A bunch of politicians, a well-known professor, Ignacio Garcia, Al Alonso a popular judge, Gilbert Vasquez, a prominent businessman.

There's a lot of shame in this country around poverty but so many of the stories of happiness and success that come out of places like public housing get forgotten. Especially in a place like San Antonio, where the history of San Antonio tends to revolve around the Alamo or maybe a King William walking tour, which is great, but it's not the whole story.

So, the Museo del Westside, we're working to document, preserve and interpret non-architectural resources in the neighborhood, as well as we're actually doing the work of saving architectural resources in the neighborhood. We do want to challenge that limited view of San Antonio history to incorporate the Westside, to incorporate the fact that San Antonio is largely a working-class city and so, where is all of that history? We are doing this through engaging the community in oral histories, which we hope will have a kind of a snowball effect to reveal further histories that we can use those stories to interpret the landscape, that we can use those stories to try to encourage the city to think beyond demolition. Are there other alternatives?

So, we want to figure out how can we connect cultural landscapes to some social justice and engage the city and its decision-making processes through our community storytelling.

Thank you.

Esperanza Peace & Justice Center

Speaker Biography

Dr. Sarah Gould, a native Texan with over a decade of museum experience, has held fellowships at the Smithsonian Institution, the Winterthur Museum, and the American Antiquarian Society, and is a National Association of Latino Arts and Culture (NALAC) Leadership Institute alumna. As lead curator at the UTSA Institute of Texan Cultures, she curated over a dozen exhibits on history, art, and culture and managed one of the state’s most significant oral history programs.

Additionally, she is the co-founder and co-chair of Latinos in Heritage Conservation, a national organization that promotes historic preservation within American Latino communities and advocates for the protection of American Latino tangible and intangible heritage at local, state, and national levels. She also serves on the boards of El Camino Real de los Tejas National Historic Trail Association and the Friends of the Texas Historical Commission, and is an active member of the Westside Preservation Alliance, a coalition dedicated to promoting and preserving the working-class architecture of San Antonio’s historic Westside. Dr. Gould received a BA in American Studies from Smith College and an MA and PhD in American Culture from the University of Michigan.