Last updated: May 28, 2025

Article

Influenza (Flu)

(This page is part of a series. For information on other illnesses that can affect NPS employees, volunteers, commercial use providers, and visitors, please see the NPS A–Z Health Topics index.)

CDC

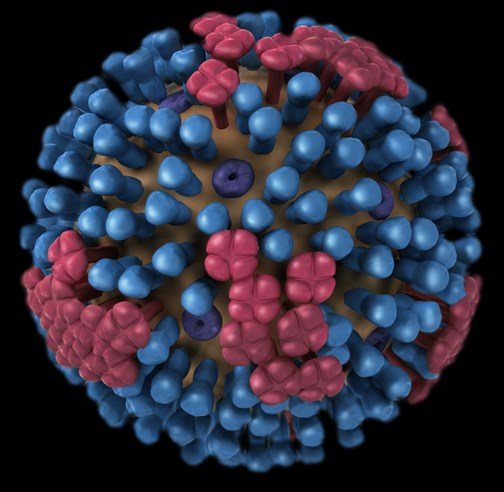

Humans: There are four types of influenza (flu) viruses, but most human disease is caused by Influenza A or Influenza B. Influenza A viruses are divided into subtypes (e.g., H3N2, H5N1) based on two proteins on their surface, hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). Influenza B viruses are divided into lineages (e.g., Victoria, Yamagata). Both types of flu viruses cause a contagious respiratory illness with symptoms that include fever, cough, sore throat, runny or stuffy nose, muscle or body aches, headaches, and fatigue. A person becomes infected with a flu virus by inhaling droplets that contain infectious virus or, less commonly, by touching a virus-contaminated surface or object and then touching their nose, mouth, or eyes. People usually get sick within 1–4 days after being exposed. People are most contagious in the first 3–4 days after symptoms start. Flu may be mild in some people but can cause hospitalization and even death in others. People at higher risk for flu complications include children younger than 5 and especially younger than 2 years of age, pregnant women, the elderly, American Indians and Alaska Natives, and people with weakened immune systems or who have underlying medical conditions. Flu viruses change quickly, and the predominant flu virus can change from one season to the next or within a season. The flu vaccine is adjusted each season to account for projected changes in the virus. There are also antiviral drugs for flu, which can lessen symptoms, shorten the duration of symptoms, and may reduce the risk of complications. They are most effective if started within two days of becoming sick.

Animals: Influenza A viruses have been identified in many different domestic animal species, such as poultry, pigs (swine), horses, dogs, and cats. With respect to wildlife, avian influenza is most typically associated with wild birds; however, other wildlife species (e.g., marine mammals, foxes, bears, etc.) are also susceptible to infection. Occasionally, influenza viruses can be transmitted between animals (e.g., birds and pigs) and humans, and this is called zoonotic influenza. When a host is simultaneously infected with different flu viruses, the viruses can combine with each other to produce a new viral strain, which has the potential to cause greater disease severity or be more transmissible in both humans and animals. In birds, viruses are classified into two categories: low pathogenicity avian influenza (LPAI) viruses and highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) viruses. These categories refer to the molecular characteristics of the virus and the virus’s ability to cause disease and mortality in chickens, not to the severity of illness in humans. In poultry, some LPAI can evolve into HPAI. Susceptible birds become infected when they have contact with the virus, as it is shed in the saliva, nasal secretions, and feces of infected birds or through contact with contaminated surfaces. Wild birds may have additional routes of exposure, including contaminated water and eating infected waterfowl. Because avian migratory pathways around the world are connected, avian influenza can be introduced into new places. In the U.S., poultry are not vaccinated for Avian Influenza. Currently, AI vaccines to protect poultry are being explored and considered for future use. When domestic poultry are infected, the risk increases for humans that work with poultry. Human infections have occurred uncommonly and sporadically. The CDC reported the first case of human HPAI H5 bird flu in the U.S. in April 2022. The case occurred in a person who had direct exposure to poultry and was involved in the depopulating of poultry with presumptive H5N1 bird flu. There have also been four human infections with LPAI in the United States, resulting in mild-to-moderate illness.

Swine influenza, also caused by type A influenza viruses, do not usually cause infections in humans, but rare human infections have been reported. Flu viruses in pigs can be transmitted to people through droplets, but transmission from eating pork is not known to occur. Influenza vaccines for swine are available, although they are not 100% effective.

Equine influenza, which occurs in horses, can cause an antibody response in some people but has not been known to cause human illness.

Environment: Flu viruses can live in the environment for up to 48 hours. Flu viruses are killed by heat above 75° C and can be killed by common household products, including products containing chlorine, hydrogen peroxide, detergents (soaps), iodine-based antiseptics, and alcohols. See Resource section below for resources on on specific disinfectants that will kill flu viruses.

PREVENTION

- Get a seasonal flu vaccine! This does not protect against avian influenza but does protect against the seasonal influenza viruses circulating among humans. Although the vaccine is not 100% effective, it can prevent disease, reduce the risk for hospitalization, and may make illness milder if you do get sick. It is important to get a flu shot annually since flu viruses change from season to season and because immunity decreases over time and needs to be boosted.

- Avoid close contact with people or animals when you or they are sick.

- Cover your nose and mouth with a tissue when you cough or sneeze and wash your hands afterwards. Avoid touching your eyes, nose, and mouth.

- Wash your hands often with soap and water. If soap and water are not available, use an alcohol-based hand rub.

- Clean and disinfect surfaces and objects that may be contaminated with viruses that cause illness. The label should state whether the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has approved the product for effectiveness against influenza.

- NPS workers:

- Utilize safe work practices and personal protective equipment according to the USGS Safe Work Practices for Working With Wildlife when handling live or dead birds or other animals, including swine.

- Avoid touching your face (eyes, nose, mouth) and wash your hands after contact with birds.

- Domestic poultry owners: Practice good biosecurity, including avoiding adding new birds from unknown sources, eliminating contact with wild birds, and limiting outside human contact with a flock. More information can be found in USDA’s “Defend the Flock” in the Resources below.

- If you are sick, consider getting tested to help distinguish flu from other illnesses, including COVID-19 and Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV).

- If you have the flu, stay home. The CDC recommends that you stay home for least 24 hours after your fever is gone except to get medical care or other necessities. Fever should be gone without the need to use a fever-reducing medicine.

- Contact your healthcare provider to determine whether you would benefit from antiviral treatment. Many people with flu have mild illness and do not need medical care or antiviral drugs. However, if symptoms continue to worsen or become severe (including difficulty breathing, shortness of breath, chest or abdominal pain, sudden dizziness, confusion, severe or persistent vomiting) or you are at higher risk for flu complications, you may need treatment.

- Report concerns about sick or dead wildlife to the park resource manager and the Wildlife Health Branch at npsdiagnostics@nps.gov.

For more information on bird flu safety in national parks; including symptoms in wildlife, visitor precautions, and reporting guidance, visit: Bird Flu (U.S. National Park Service)

- NPS Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Directorate (NRSS) Avian Influenza site (internal)

- DOI: Updated Employee Health and Safety Guidance for Wild Bird Management Activities and Avian Influenza Surveillance, 2022

- CDC: Influenza webpage

- CDC Recommendations for Worker Protection and Use of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) to Reduce Exposure to Novel Influenza A Viruses Associated with Severe Disease in Humans

- EPA’s List M: Registered Antimicrobial Products with Label Claims for Avian Influenza

- EPA: Antimicrobial products registered for use against the H1N1 Flu and Other Influenza A Viruses on Hard Surfaces

- USDA APHIS Avian Influenza

- USDA APHIS Wild Bird Avian Influenza Surveillance

- USDA APHIS | Defend the Flock - Resource Center

- USGS. Distribution of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza in North America.

- USGS Guide to Safe Work Practices for Working with Wildlife