Last updated: November 18, 2021

Article

Life in the Indigenous Chesapeake

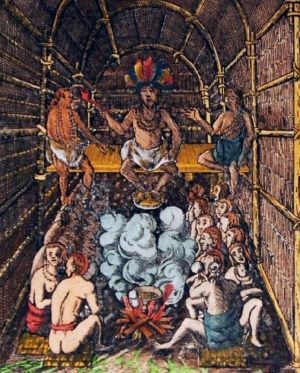

Detail from a 1630 map by Henricus Hondius based on John Smith's map of Virginia.

Some 50,000 people called the Chesapeake Bay home before the English ever set foot on its shores.

For native peoples, the Chesapeake Bay was a source of sustenance, a transportation lifeline, and a home. Traditional lifestyles revolved around the Bay's natural resources. The waters teemed with life, the tall forests sheltered an immense variety of animals, birds, and plants, and the soil was rich and fertile.

There was not one single culture that defined people in this area. Instead, there was a diversity of cultures, languages, political groups, and identities. There were at least three different language families and dozens of dialects represented.

Today, American Indians retain knowledge of their culture and history despite centuries of assimilation and erasure. By combining this knowledge with the research of archaeologists, scientists, anthropologists, and historians, it is possible to reconstruct an image of the Chesapeake region before the arrival of English settlers.

Three major language families are represented in the Chesapeake Bay watershed. Within these language families, countless local dialects were spoken.

Algonquian

Most tribes in the region speak Algonquian languages - a family of languages widespread among native peoples from northern Canada to the Carolinas. Among the Algonquian speakers are the Powhatan-descendent tribes, the Chickahominy, the Piscataway, the Nanticoke, and the Assateague.

Iroquoian

Iroquoian languages are spoken by peoples living in the northern reaches of the watershed, primarily the Susquehanna River Valley. The Great Lakes region is the heartland of the Iroquoian language group, with groups of speakers also found in what is now southern Virginia, North Carolina, and Tennessee.

Siouan

Siouan languages are spoken by tribes throughout the Great Plains region. A smaller pocket of speakers is also found in the western parts of what is now Virginia, West Virginia, and North Carolina. The Monacan, located along the Upper James River, speak a Siouan language.

American Indians harvested shellfish, gathered wild edibles, hunted deer and other game, and fished on a large scale. To supplement this diet, many groups cultivated crops in semi-permanent towns located along riversides. During the winter, towns would often move to hunting camps in the forest.

Many tools and materials were needed to sustain the town. Some skills were practiced by the general population, while other trades were likely more specialized. Canoes were an essential item, allowing for quick transportation, fishing, and gathering aquatic plants. In the Chesapeake, the dugout canoe was the chosen style.

Other examples include pottery, needed for the storage of food and cooking over a fire. Cordage and mats made of grasses, reeds, and tree bark were used to construct houses and make fishing nets. Clothing was made from deer hide, as well as furs in the wintertime. Things like arrowheads, knives, and axes were shaped out of stone.

Edible and medicinal plants >

How did animals provide food, clothing, and tools? >

Techniques and technologies for fishing and hunting >

Indigenous peoples living in the Chesapeake Bay watershed are diverse, each with their own, unique culture and history. There are some aspects, however, that are common to many tribes in the region.

Matrilineal societies

Most of the indigenous peoples of the Chesapeake identified their lineage through their mothers, not their fathers. This meant that a chief’s brothers and sisters were next in line for the role, not his own children. Women could hold leadership roles, including the role of chief.

Names

People had several names, including a personal name, a name used when they were a child, and a name taken when they were older. Names could be earned to reflect achievements or characteristics.

Religion

Religion was widely practiced in indigenous cultures. Creation stories explained the origin of the world and the role of humans within it, priests provided advice to leaders and the larger community, and prayer was a part of everyday life.

Gender Roles

To provide for all of the tribe’s needs, men and women had different responsibilities. Women did the farming, gathering, and housebuilding. Men hunted and defended the tribe in times of conflict.

Homes

American Indians in the Chesapeake constructed a type of house known as a longhouse. The women of the tribe constructed them by building a wooden frame with an arched roof and covering the frame with mats woven from reeds. Multiple families might share a single longhouse, and some were up to 70 feet long. The Virginia Algonquian word for longhouse is yihakan.

Seasonality

The lifestyle as well as ceremonial practices of tribes revolved around the changing seasons. Early spring, or Cattapeuk in the Virginia Algonquian language, was the planting season when migrating fish were netted from the rivers. Next was Cohatayough when crops were tended. Nepinough, or early fall, was time to reap and celebrate the harvest. Early winter, or Taquitock, saw the townspeople move to interior hunting camps. Popanow, late winter, was the hungriest time of year when game was scarce and food stores ran low.

Marriage

What we know about marriage among indigenous peoples of the Chesapeake comes from secondhand accounts by English colonists. We know that it was acceptable for a man to take multiple wives. It was also possible for a woman to divorce her husband if she became dissatisfied. Women had to agree to the marriage. The man’s family had to pay the wife’s family a dowry to account for the labor they would lose in her absence. Marriage was not as strict or exclusive as in Europe. For example, political marriages were often arranged, but they sometimes would only last long enough for an heir to be born.

Gift Economy: For the indigenous tribes of the Chesapeake, the giving of gifts was a way of maintaining positive relationships between different groups. Receiving a gift meant that you were indebted to return the favor at a later date. The specifics of what was given did not matter as much as the act of giving itself. Gift-giving had the power to further alliances as well as to break them.