Last updated: December 2, 2021

Article

Indigenous Diplomacy: The Ute-Comanche Treaty of 1786

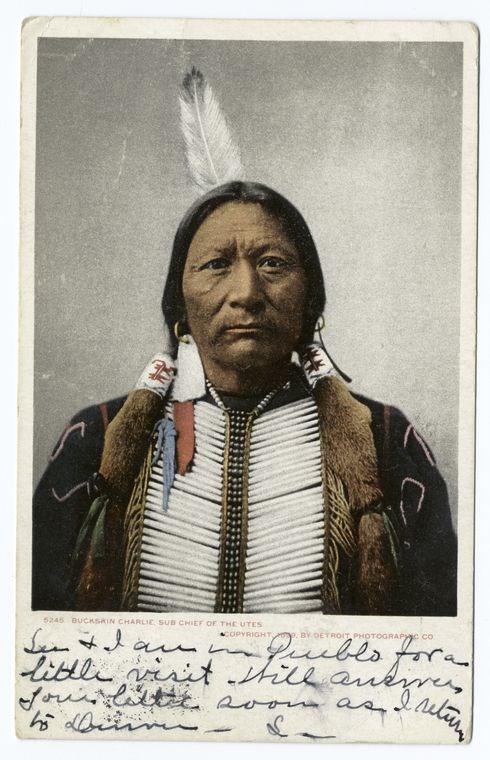

Image/The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection

History classes are filled with treaties between colonial powers and Indigenous peoples. Yet we learn considerably less about treaties between Native nations. A 1786 agreement between Utes and Comanches, poorly documented by Spanish sources, provides an opportunity to see history from a different perspective.

In the 1780s, powerful groups—Navajos, Apaches, Comanches, Utes, and Spaniards—occupied present-day New Mexico, which was then the northern tip of New Spain (Spain’s colonies in the Americas). Formerly allies, Comanches and Utes became enemies by 1750; around the same time, Utes and Spaniards became friendly with one another. Unbeknownst to Utes, Spaniards began attempting to make peace with Western Comanches, whose raids had long threatened New Mexico.

In the summer of 1785, Western Comanches met along the Arkansas River to discuss a potential treaty with their Spanish neighbors. Here, the different groups that made up the Western Comanches chose a leader for the peace process: Ecueracapa, a leader of the Kotsotekas (one of the groups that made up the Western Comanches). The Comanches assembled also decided to send a delegation to Santa Fe, which arrived on December 30, 1785 and departed on January 3, 1786.

Led by the Moache chief Moara, a group of Utes arrived four days later to protest the treaty talks—which they feared would threaten their alliance with Spanish forces. Though Moara was unable to keep New Mexico governor Juan Bautista de Anza from pursuing peace with the Comanches, the Ute leader asked to be present when the next Comanche delegation came to Santa Fe.

Arriving in Santa Fe on February 25, Ecueracapa—fresh from four Western Comanche councils discussing the treaty—related his people’s demands. They wanted a full peace with Spaniards and free trade with the important outposts of Taos, Pecos, and Santa Fe. Lastly, Comanches agreed to ally with Spaniards against the Apaches (who interfered with Comanche hunting and trading). Eager to end Comanche raids, Anza would later accept these terms in front of a gathering of Comanche headmen at Pecos Pueblo.

After hearing Ecueracapa’s demands, Anza introduced the Utes and Comanches, who held discussions on their own. They talked for three days before coming to an understanding on February 28, 1786, which likely involved renewed commitments of peace and trade. Spanish sources are silent on the Ute-Comanche talks; indeed, neither group told Anza about the negotiations. Nonetheless, the Spanish-Comanche and Ute-Comanche treaties ushered in an era of peace and prosperity in New Mexico.

There are some important lessons here. Indigenous communities like the Comanches and Utes were skilled diplomats. They dealt smartly with colonial powers, and with each other. Spanish sources give us more insight into the Spanish-Comanche treaty, but that doesn’t mean we should discount the Ute-Comanche treaty. Whether intentionally or not, historians often view history through the eyes of whoever made the written record of the event; the Ute-Comanche treaty, then, allows us to envision the Southwest through non-Spanish eyes.

This is not to say that all memory of the agreement has been lost. Indeed, Utes and Comanches met in southern Colorado in 1977—almost two centuries later—to renew their dedication to the pact of 1786. While Spanish sources offer few details about the Ute-Comanche treaty, it is obvious that both communities involved retain strong memories of the agreement.

- Ned Blackhawk, Violence Over the Land: Indians and Empires in the Early American West (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2006), 45-54, 103-6.

- Pekka Hämäläinen, The Comanche Empire (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 119-22.

- Damon Toledo, “Ute Nation Remembers Peace Treaty,” Southern Ute Drum, 10 June 2016, https://www.sudrum.com/culture/2016/06/10/ute-nation-remembers-peace-treaty/.

- John R. Wunder, “’That No Thorn Will Pierce Our Friendship’: The Ute-Comanche Treaty of 1786,” Western Historical Quarterly 42, no. 1 (Spring 2011), 4-27.

- Image: The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. "Buckskin Charlie, Sub Chief of the Utes, Indian" The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1900 - 1902. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47d9-9bf4-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99