Last updated: October 2, 2023

Article

What Was Lost?

NPS photos

Deciding what to preserve is a constant question for the National Park Service. Who decides what is important? Does the object, building, or land support the mission of the agency? Who has ownership of the item or story? Not all items, buildings, or lands can be preserved by the National Park Service, and what is important to one generation may not be as valued decades later.

The creation of Independence National Historical Park ensured the preservation of Independence Hall and many surrounding buildings for the enjoyment of future generations.

But what would happen to the 20th century neighborhood that now housed a park dedicated to the 1770s? What about all of the impressive offices, banks, and other buildings that lined the surrounding city blocks? By the creation of the national park in 1948, city and state groups had already started making decisions of what to keep and what to tear down, but many difficult choices remained.

NPS photo

Designing a National Park

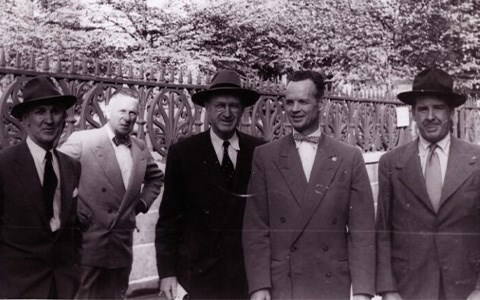

Designing a National Park in a nearly three hundred year-old city required significant creativity. Everyone involved had a different idea of what the surrounding area should look like and which buildings should be preserved The National Park Service brought in advisors and planners, including Charles Peterson. A seasoned architect, Peterson and his work group prepared multiple different plans for this new park. However, his passion for the many centuries of American architecture sparked disagreement with other officials who valued colonial buildings above all else, including Judge Edwin Lewis and the National Park Shrines Committee.

NPS photo

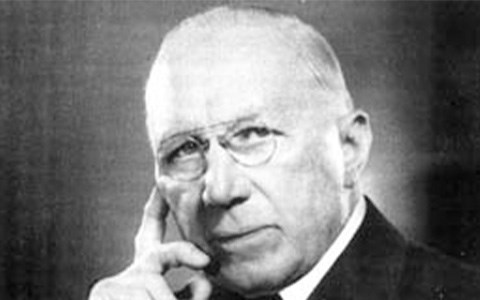

Judge Lewis

Judge Lewis and the Shrines Committee were integral to the passage of legislation that created Independence National Historical Park. Over the years they imagined what a National Park in Philadelphia would look like when their goal was fulfilled. Judge Lewis dreamt of visitors strolling colonial streets and exploring original and recreated colonial homes on their way to visit Independence Hall and the Liberty Bell. This would require the demolition of many post 1800 buildings.

NPS photo

A Differing Opinion

Architect Charles Peterson disagreed with Lewis’ desire to recreate the colonial landscape of Old City. Peterson argued that the neighborhoods surrounding Independence Hall flourished as Philadelphia's government and financial center for decades; the area housed the ports, docks, and workers that gave 19th century Philadelphia the nickname “Workshop of the World”; and that freezing the area in the colonial era would erase the neighborhood’s contributions to the city and create a fairy tale version of 1770s Philadelphia.

Peterson's group reimagined the urban landscape—linking highlighted 1770s buildings to their newer counterparts with small courtyards and gardens, historic streets and brick sidewalks. Despite proposing multiple plans and gaining support amongst the architectural community across the country and groups in the city, Peterson’s efforts to preserve many of the buildings from the 1800s and 1900s failed. Lewis, the city of Philadelphia, and shifts in the National Park Service mission guided the decision that the landscape should emulate the conditions that existed from 1774 to 1800—demolition intensified.

Notable Architects, Pioneering Buildings

While these buildings no longer stand, architects, locals, and historians continue to value them as notable contributions to Philadelphia's unique architectural landscape.

NPS photo

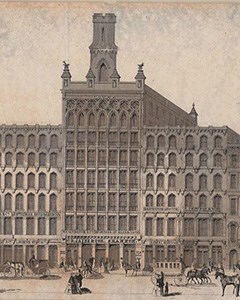

One of the grandest on buildings on Chestnut Street, the Guarantee Trust and Safe Deposit Company building’s ornate towers loomed in front of Carpenter’s Court. Aiming to make the building fireproof, architects and builders used as little wood as possible in the design and construction of the building. It was demolished in 1957 to clear the view of Carpenters’ Hall.

NPS photo

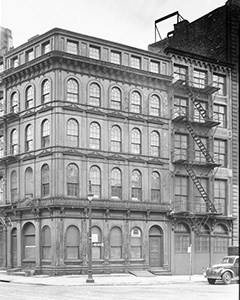

Provident Life and Trust Building

Across the street diagonally from the Guarantee Trust building stood the Provident Life and Trust building. Starting as a small bank, the building grew substantially during its decades at the corner of 4th and Chestnut Streets. National Park Service historical architect Penelope Batcheler took this photo during the building’s demolition in 1956.

The Library Company of Philadelphia

Drexel Building

Built on the site of the original Library Hall of the American Philosophical Society, the Drexel Building towered over its neighbor Old City Hall on 5th and Chestnut Streets. Ten stories tall, it was constructed as an addition to an earlier Drexel bank building, and around a separate bank building whose owner would not sell, enveloping it almost entirely. Demolished in 1956, you can find the Signers Garden and reconstructed Library Hall of the American Philosophical Society at this spot.

The Library Company of Philadelphia

Jayne Building

While we would not think of eight stories as a particularly tall building today, the Jayne Building stood high above its neighbors when constructed in 1850. A fire caused the loss of the building’s tower in the 1870 and buildings towered around it by the 1950s, but Peterson and his group fought to preserve one of the first ‘skyscrapers’ in the United States. The Museum of the American Revolution now stands at the site.

Library of Congress

Penn Mutual Building

Constructed the same year as its towering neighbor, the Penn Mutual Building at 3rd and Chestnut streets stood dwarfed by the Jayne Building’s many floors. As one of the first buildings in the country fabricated from cast iron, Peterson felt it deserved preservation. It was demolished in 1956.

Now and the Future

While many of the structures Peterson and his group wished to preserve met demolition permits, some of his work can still be seen at the park today. Though the landscape is very different from the 1950s and does not resemble the 1770s, you can explore the park’s courtyards, small gardens, and public squares by walking the brick-lined sidewalks. The Second Bank of the United States and the Merchant’s Exchange Building’s early 19th century marble facades are favorite backdrops for photos.

The National Park Service learned from the monumental changes to the landscape they made in the 1950s. More recently, major changes to the park’s landscape—including removing, adding, or extensively altering buildings—require broad community input. The National Park Service aims to work with local communities to preserve and maintain urban neighborhoods and landscapes.