Last updated: June 23, 2023

Article

A Changing Neighborhood

Public Domain

Home and Work in Philadelphia's Oldest Neighborhoods

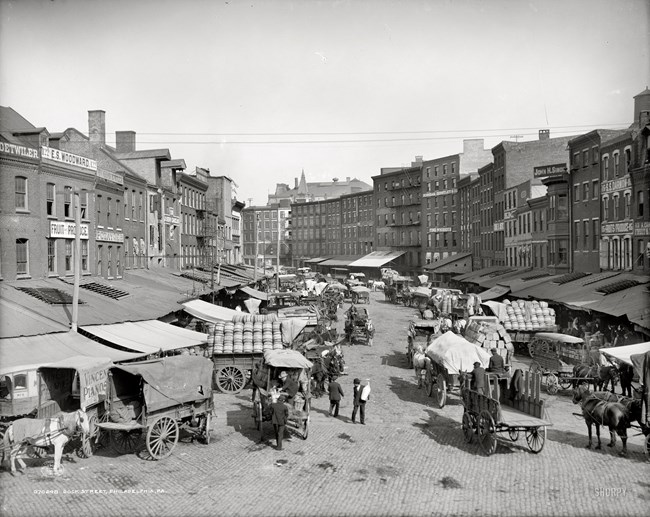

The neighborhoods surrounding Independence National Historical Park are some of the oldest in the city. With the development of the National Park and broader urban renewal movements in the 1950s and 1960s, city, state, and federal governments wanted to make the nearby neighborhoods feel connected to the new park. Authorities wanted to "clean up" what many considered a slum and provide a city neighborhood park that visitors could explore. The sweeping changes transformed the area, fundamentally-altering the buildings you see, the businesses you visit, and the faces of people who live there.One of these neighborhoods, the Fifth Ward, borders Independence National Historical Park. Historically reaching from Chestnut Street to South Street, and from 7th Street to the Delaware River, most of this area is now considered the Society Hill neighborhood. The ward and its residents witnessed a momentous, and at times violent, history in the shadow of Independence Hall.

With their proximity to the Delaware River, the neighborhood's residents and businesses supported the busy docks. Immigrants and free and enslaved Black Philadelphians called the ward home. Residents relied on jobs in the densely packed markets, warehouses, and factories connected to the substantial shipping and manufacturing industry of 19th and early 20th century Philadelphia.

Smithsonian Institute

Political Tension Creates Political Violence

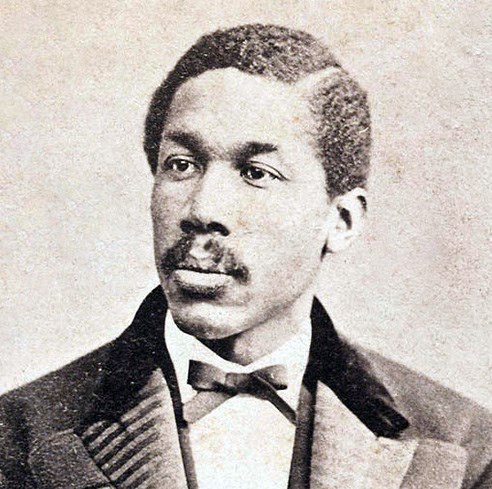

Due to its busy and relatively poor residents, some Philadelphia politicians saw the ward ripe for corrupt political manipulation—leading to violence and upheaval. The demographic mixture of new immigrants and free Blacks in the 1800s coupled with crooked politicians led to race riots and nativist riots.Tensions reached a breaking point during the 1871 presidential election—the first election where Black Americans could vote. Octavius Catto, a prominent Black rights activist, was murdered during election day violence in the Fifth Ward.

In 1917 James Carey ran against Issac Deutsch for Select Councilman. Deutsch paid New York gang members to attack Carey and the ensuing mayhem ended in the murder of a police officer. Due to his involvement in the race and the resulting violence, Philadelphia Mayor Thomas B Smith was indicted for election interference. Political violence decreased after World War I, as the economic and demographic landscape of the city changed.

Temple University Libraries

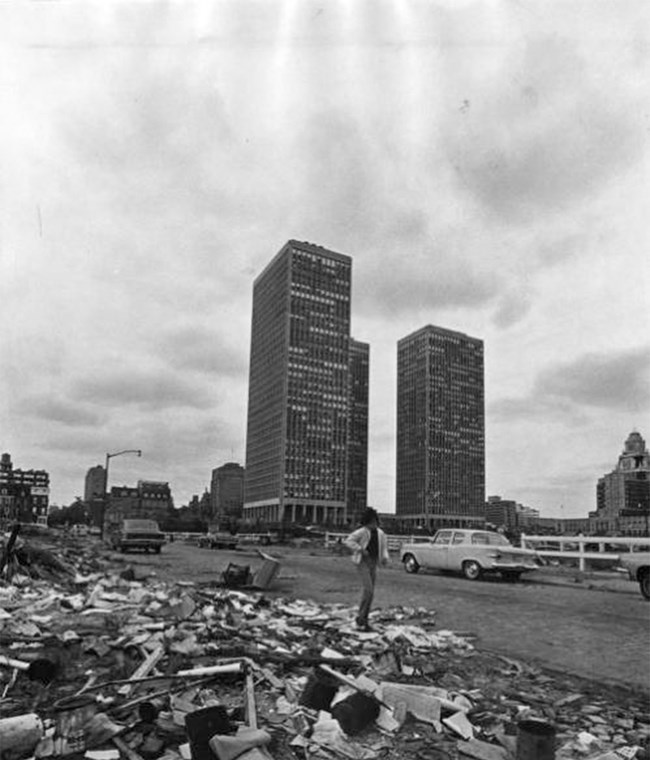

From 5th Ward to Society Hill

By the time Independence National Historical Park was founded in 1948, businesses and residents struggled economically as industry moved westward. Russian Jewish immigrants and Black Philadelphians continued to live here as the mills and the docks they had worked in closed. City planners and federal officials, led by city planner Edmund Bacon and Mayor Richardson Dilworth, saw the creation of the National Park spark a rehabilitation effort. With an influx of federal urban renewal money, they sought to remodel the neighborhood's homes, businesses, and offices—but first they wanted to remodel the area's name. Choosing to shed the reputation of the "Fifth Ward," city developers called it by its historic designation—Society Hill.In the redesignated Society Hill area, residents could keep their homes if they could prove their ability to pay for costly repairs. The city reissued deeds with detailed restoration agreements attached to residents who stayed in the neighborhood. People who rented or who could not agree to these terms of the restoration agreements had their properties condemned. City officials interviewed prospective buyers to ensure they could meet the repair schedule and costs. More than a third of the neighborhood's residents were displaced.

By the 1970s, many historic homes were rehabilitated and modern housing and businesses filled in the spaces left by the condemned and demolished structures. Groups like the Society Hill Civic Association, and the Philadelphia Historical Commission continue to work with the city to maintain the neighborhood's historic designation and look. Society Hill is now one of the most affluent neighborhoods in Philadelphia.