Last updated: April 2, 2025

Article

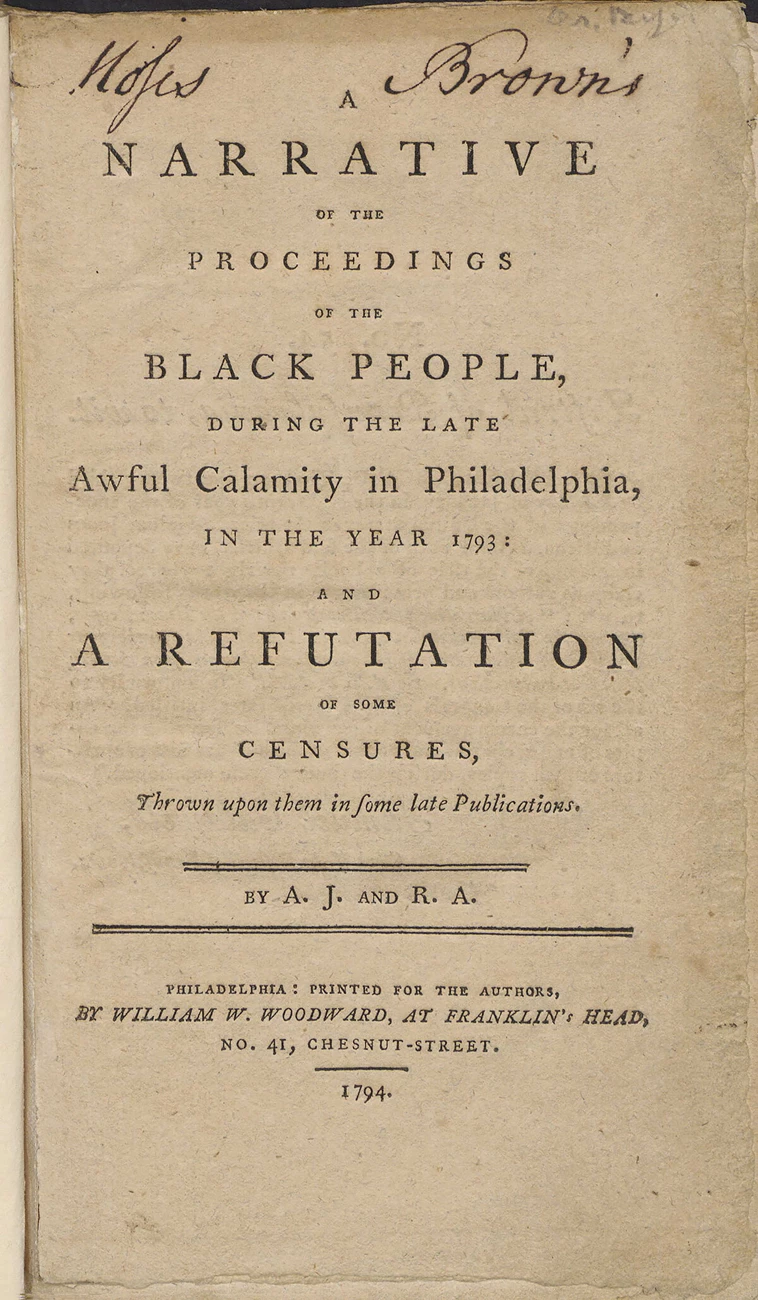

A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People, During the Late Awful Calamity in Philadelphia, 1793

Courtesy of Harvard University

Title: A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People, During the Late Awful Calamity in Philadelphia, in the year 1793: And a Refutation of Some Censures Thrown upon then in some late Publications.

Date: 1794

Location: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Object Information: Paper document, 28 p.

Repository: CURIOSity Collections, Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine, Harvard University, F158.44.J7 https://nrs.lib.harvard.edu/urn-3:hms.count:1115398

Description:

This pamphlet, published in 1794, was written by Richard Allen and Absalom Jones to refute charges leveled by many against the actions of the African American community in Philadelphia during the Yellow Fever epidemic of 1793. Allen and Jones detailed the reasoning and actions of the African American community stepping in as nurses, caretakers, and gravediggers. African American community members sought to help their neighbors, no matter who they were, when many wealthier, predominately white European American neighbors fled the city. Initially, Benjamin Rush, a physician and signer of the Declaration of Independence, and many others pushed for the community’s help based the scientific racism beliefs in the era that people of African descent were immune to the disease. Despite the best efforts of the community and others, more than 5,000 people, both white European and Black Philadelphians, perished from the disease. As it is mentioned in the Narrative, some people were buried in the "Potter's field," now known as Washington Square.

Date: 1794

Location: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Object Information: Paper document, 28 p.

Repository: CURIOSity Collections, Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine, Harvard University, F158.44.J7 https://nrs.lib.harvard.edu/urn-3:hms.count:1115398

Description:

This pamphlet, published in 1794, was written by Richard Allen and Absalom Jones to refute charges leveled by many against the actions of the African American community in Philadelphia during the Yellow Fever epidemic of 1793. Allen and Jones detailed the reasoning and actions of the African American community stepping in as nurses, caretakers, and gravediggers. African American community members sought to help their neighbors, no matter who they were, when many wealthier, predominately white European American neighbors fled the city. Initially, Benjamin Rush, a physician and signer of the Declaration of Independence, and many others pushed for the community’s help based the scientific racism beliefs in the era that people of African descent were immune to the disease. Despite the best efforts of the community and others, more than 5,000 people, both white European and Black Philadelphians, perished from the disease. As it is mentioned in the Narrative, some people were buried in the "Potter's field," now known as Washington Square.

TRANSCRIPT

Moses Brown's [cursive handwriting]

A

NARRATIVE

OF THE

PROCEEDINGS

OF THE

BLACK PEOPLE

DURING THE LATE

Awful Calamity in Philadelphia,

IN THE YEAR 1793 :

AND

A REFUTATION

OF SOME CENSURES,

Thrown upon them in some late Publication.

By A.J. and R.A.

PHILADELPHIA : PRINTED FOR THE AUTHORS,

BY WILLIAM W. WOODWARD, AT FRANKLIN’S HEAD,

NO. 41, CHESNUT-STREET.

1794

[Page 2]

No. 54

District of Pennsylvania, to wit.

BE IT REMEMBERED, That on the twenty-third day of January, in the eighteenth year of the Independence of the United States of America, Absalom Jones and Richard Allen, both of the said District, have deposited in this office, the title of a book, the right whereof they claim as authors and proprietors, in the words following, to wit : “ A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People, during the late awful Calamity in Philadelphia, in the year 1793: and a Refutation of some Censures thrown upon then in some late Publications. By A. J. & R.A.” In conformity to the act of the Congress of the United States, intitled, “An act for the encouragement of learning, by securing the copies of maps, charts, and books, to the authors and proprietors of such copies, during the times therein mentioned.”

Samuel Caldwell,

Clerk of the District of Pennsylvania.

[Page 3]

A NARRATIVE, &c.

IN consequence of a partial representation of the conduct of the people who were employed to nurse the sick, in the late calamitous state of the city of Philadelphia, we are solicited, by a number of those who feel themselves injured thereby, and by the ad- vice of several respectable citizens, to step forward and declare facts as they really were; seeing that from our situation, on account of the charge we took upon us, we had it more fully and generally in our power, to know and observe the conduct and behavior of those that were so employed.

Early in September, a solicitation appeared in the public papers, to the people of colour to come forward and assist the distressed, perishing, and neglected sick; with a kind of assurance, that people of our colour were not liable to take the infection. Upon which we and a few others met and consulted how to act on so truly alarming and melancholy an occasion. After some conversation, we found a freedom to go forth, confiding in him who can preserve in the midst of a burning fiery furnace, sensible that it was our duty to do all the good we could to our suffering fellow mor- tals. We set out to see where we could be useful. The first we visited was a man in Emfley's alley, who was dying, and his wife lay dead at the time in the house, there were none to assist but two poor helpless children. We administered what relief we could, and applied to the overseers of the poor to have the woman buried. We visited upwards of twenty families that

A 2

[Page 4]

4 A NARRATIVE,&c.

day-they were scenes of woe indeed! The Lord was pleased to strengthen us, and remove all fear from us, and disposed our hearts to be as useful as possible.

In order the better to regulate our conduct, we called on the mayor next day, to consult with him how to proceed, so as to be most useful. The first object he recommended was a strict attention to the sick, and the procuring of nurses. This was attended to by Absalom Jones and William Gray; and, in order that the distressed might know where to apply, the mayor advertised the public that upon application to them they would be supplied. Soon after, the mortality increasing, the difficulty of getting a corpse taken away, was such, that few were willing to do it, when offered great rewards. The black people were looked to. We then offered our Services in the public papers, by advertising that we would remove the dead and procure nurses. Our services were the production of real sensibility; - we sought not fee nor reward, until the increase of the disorder rendered our labour so arduous that we were not adequate to the service we had assumed. The mortality increasing rapidly, obliged us to call in the assistance of five* hired men, in the awful discharge of interring the dead. They, with great reluctance, were prevailed upon to join us. It was very uncommon, at this time, to find any one that would go near, much more, handle, a sick or dead person.

Mr. Carey, in page 106 of his third edition, has observed, that, "for the honor of human nature, it ought to be recorded, that some of the convicts in the gaol, a part of the term of whose confinement had been remitted as a reward for their peaceable, orderly behavior, voluntarily offered themselves as nurses to attend the sick at Bush-hill; and have, in that capacity, conducted themselves with great fidelity, &c. Here

*Two of whom were Richard Allen’s brothers.

[Page 5]

A NARRATIVE, &c. 5

it ought to be remarked, (although Mr. Carey hath not done it) that two thirds of the persons, who rendered these essential services, were people of colour, who, on the application of the elders of the African church, (who met to consider what they could do for the help of the sick) were liberated, on condition of their doing the duty of nurses at the hospital at Bush- hill; which they as voluntarily accepted to do, as they did faithfully discharge, this severe and disagreeable duty.—May the Lord reward them, both temporally and spiritually.

When the sickness became general, and several of the physicians died, and most of the survivors were exhausted by sickness or fatigue; that good man, Doctor Rush, called us more immediately to attend upon the sick, knowing we could both bleed; he told us we could increase our utility, by attending to his instructions, and accordingly directed us where to procure medicine duly prepared, with proper directions how to administer them, and at what stages of the disorder to bleed; and when we found ourselves incapable of judging what was proper to be done, to apply to him, and he would, if able, attend them himself, or send Edward Fisher, his pupil, which he often did; and Mr. Fisher manifested his humanity, by an affectionate attention for their relief.– This has been no small satisfaction to us; for, we think, that when a physician was not attainable, we have been the instruments, in the hand of God, for saving the lives of some hundreds of our suffering fellow mortals.

We feel ourselves sensibly aggrieved by the censorious epithets of many, who did not render the least assistance in the time of necessity, yet are liberal of their censure of us, for the prices paid for our services, when no one knew bow to make a proposal to any one they wanted to assist them. At first we made no charge, but left it to those we served in removing their dead,

A3

[Page 6]

6 A NARRATIVE, &c.

to give what they thought fit - we set no price, until the reward was fixed by those we had served. After paying the people we had to assist us, our compensation is much less than many will believe.

We do assure the public, that all the money we have received, for burying, and for coffins which we our- selves purchased and procured, has not defrayed the expence of wages which we had to pay to those whom we employed to assist us. The following statement is accurately made:

CASH RECEIVED.

The whole amount of Cash we received for burying the dead, and for burying beds, is, - -£233 10 4

CASH PAID.

For coffins, for which we have received nothing - £33 0 0

For the hire of five men, 3 of them 70 days each, and the other two, 63 days each, at 22s 6 per day, - - - 378 0 0

411 0 0

Debts due us, for which we expect but little, - £110 0 0

From this statement, for the truth of which we solemnly vouch, it is evident, and we sensibly feel the operation of the fact, that we are out of pocket, - - - - £ 177 9 8

Besides the costs of hearses, the maintenance of our families for 70 days, (being the period of our labours) and the support of the five hired men, during the respective times of their being employed; which expences, together with sundry gifts we occasionally made to poor family, might reasonably and intro-

[Page 7]

A NARRATIVE, &c. 7

-duced, to show our actual situation with regard to pro- fit-but it is enough to exhibit to the public, from the above specified items, of Cash paid and Cash received, without taking into view the other expences, that, by the employment we were engaged in, we have lost £177 9 8. But, if the other expences, which we have actually paid, are added to that sum, how much then may we not say we have suffered! We leave the public to judge.

It may possibly appear strange to some who know how constantly we were employed, that we should have received no more Cash than £233 10 4. But we repeat our assurance, that this is the fact, and we add another, which will serve the better to explain it: We have buried several hundreds of poor persons and strangers, for which service we have never received, nor never asked any compensation.

We feel ourselves hurt most by a partial, censorious paragraph, in Mr. Carey’s second edition of his account of the sickness, &c. in Philadelphia; pages 76 and 77, where he asperses the blacks alone, for having taken the advantage of the distressed situation of the people. That some extravagant prices were paid, we admit; but how came they to be demanded? the reason is plain. It was with difficulty persons could be had to supply the wants of the sick, as nurses;-applications became more and more numerous, the consequence was, when we procured them at six dollars per week, and called upon them to go where they were wanted, we found they were gone elsewhere; here was a disappointment; upon enquiring the cause, we found, they had been allured away by others who of- fered greater wages, until they got from two to four dollars per day. We had no restraint upon the peo- ple. It was natural for people in low circumstances to accept a voluntary, bounteous reward; especially under the loathsomness of many of the sick, when na-

[Page 8]

8 A NARRATIVE, &c.

-ture shuddered at the thoughts of the infection, and the talk assigned was aggravated by lunacy, and being left much alone with them. Had Mr. Carey been so- licited to such an undertaking, for hire, Query, "what would he have demanded? but Mr. Carey, although chosen a member of that band of worthies who have so eminently distinguished themselves by their labours, for the relief of the sick and helpless-yet, quickly after his election, left them to struggle with their arduous and hazardous talk, by leaving the city. 'Tis true Mr. Carey was no hireling, and had a right to flee, and upon his return, to plead the cause of those who fled; yet, we think, he was wrong in giving so partial and injurious an account of the black nurses; if they have taken advantage of the public distress? Is it anymore than he hath done of its desire for information. We believe he has made more money by the sale of his "scraps" than a dozen of the greatest extortioners among the black nurses. The great prices paid did not escape the observation of that worthy and vigilant magistrate, Mathew Clarkson, mayor of the city, and president of the committee-he sent for us, and requested we would use our influence, to lessen the wages of the nurses, but on informing him the cause, i. e. that of the people over- bidding one another, it was concluded unnecessary to attempt any thing on that head; therefore it was left to the people concerned. That there were some few black people guilty of plundering the distressed, we acknowledge; but in that they only are pointed out, and made mention of, we esteem partial and injurious; we know as many whites who were guilty of it; but this is looked over, while the blacks are held up to censure.—Is it a greater crime for a black to pilfer, than for a white to privateer?

We wish not to offend, but when an unprovoked attempt is made, to make us blacker than we are, it be- comes less necessary to be over cautious on that ac-

[Page 9]

A NARRATIVE,&c. 9

- count; therefore we shall take the liberty to tell of the conduct of some of the whites.

We know six pounds was demanded by, and paid, to a white woman, for putting a corpse into a coffin; and forty dollars was demanded, and paid, to four white men, for bringing it down the stairs.

Mr. and Mrs. Taylor both died in one night; a white woman had the care of them; after they were dead she called on Jacob Servoss, esq. for her pay, demanding six pounds for laying them out; upon seeing a bundle with her, he suspected she had pilfered; on searching her, Mr. Taylor's buckles were found in her pocket, with other things.

An elderly lady, Mrs. Malony, was given into the care of a white woman, she died, we were called to remove the corpse, when we came the woman was lay- ing so drunk that she did not know what we were do- ing, but we know she had one of Mrs. Malony's rings on her finger, and another in her pocket.

Mr. Carey tells us, Bush-hill exhibited as wretched a picture of human misery, as ever existed. A profli- gate abandoned set of nurses and attendants (hardly any of good charater could at that time be procured,) rioted on the provisions and comforts, prepared for the sick, who (unless at the hours when the doctors attend- ed) were left almost entirely destitute of every assist- ance. The dying and dead were indiscriminately mingled together. The ordure and other evacuations of the sick, were allowed to remain in the most offen- sive state imaginable. Not the smallest appearance of order or regularity existed. It was in fact a great hu- man slaughter house, where numerous victims were immolated at the altar of intemperance.

It is unpleasant to point out the bad and unfeeling conduct of any colour, yet the defence we have under- taken obliges us to remark, that although "hardly any of good character at that time could be procured" yet only two black women were at this time in the hospi-

[Page 10]

10 A NARRATIVE, &c.

-tal, and they were retained and the others discharged, when it was reduced to order and good government.

The bad consequences many of our colour apprehend from a partial relation of our conduct are, that it will prejudice the minds of the people in general against us —because it is impossible that one individual, can have knowledge of all, therefore at some future day, when some of the most virtuous, that were upon most praiseworthy motives, induced to serve the sick, may fall in- to the service of a family that are strangers to him, or her, and it is discovered that it is one of those stigmatised wretches, what may we suppose will be the consequence? Is it not reasonable to think the person will be abhored, despised, and perhaps dismissed from employment, to their great disadvantage, would not this be hard? and have we not therefore sufficient reason to seek for-redress? We can with certainty assure the public that we have seen more humanity, more real sensibility from the poor blacks, than from the poor whites. When many of the former, of their own accord rendered services where extreme necessity called for it, the general part of the poor white people were so dismayed, that instead of attempting to be useful, they in a manner hid themselves—a remarkable instance of this—A poor aflicted dying man, stood at his chamber window, praying and beseeching every one that passed by, to help him to a drink of water; a number of white people passed, and instead of being moved by the poor man's distress, they hurried as fast as they could out of the sound of his cries-until at length a gentleman, who seemed to be a foreigner came up, he could not pass by, but had not resolution enough to go into the house, he held eight dollars in his hand, and offered it to several as a reward for giving the poor man a drink of water, but was refused by every one, until a poor black man came up, the gentleman offered the eight dollars to him, if he would relieve

[Page 11]

A NARRATIVE, &c. 11

the poor man with a little water, "Master" replied the good natured fellow, "I will supply the gentleman with water, but surely I will not take your money for it" nor could he be prevailed upon to accept his bounty: he went in, supplied the poor object with water, and rendered him every service he could.

A poor black man, named Sampson, went constantly from house to house where distress was, and no assistance without fee or reward; he was smote with the disorder, and died, after his death his family were negleted by those he had served.

Sarah Bass, a poor black widow, gave all the assistance she could, in several families, for which she did not receive any thing; and when any thing was offered her, she left it to the option of those she served.

A woman of our colour, nursed Richard Mason and son, when they died, Richard's widow considering the risk the poor woman had run, and from observing the fears that sometimes relied on her mind, expected she would have demanded something considerable, but upon asking what she demanded, her reply was half a dollar per day. Mrs. Mason, intimated it was not sufficient for her attendance, she replied it was enough for what she had done, and would take no more. Mrs. Mason's feelings were such, that she settled an annuity of six pounds a year, on her, for life. Her name is Mary Scott.

An elderly black woman nursed --------with great diligence and attention; when recovered he asked what he must give for her services—she replied "a din- ner master on a cold winter's day," and thus she went from place to place rendering every service in her pow- er without an eye to reward.

A young black woman, was requested to attend one night upon a white man and his wife, who were very ill, no other person could be had;—great wages were offered her—she replied, I will not go for money, if I

[Page 12]

12 A NARRATIVE, &c.

go for money God will see it, and may be make me take the disorder and die, but if I go, and take no money, he may spare my life. She went about nine o'clock, and found them both on the floor; she could procure no candle or other light, but staid with them about two hours, and then left them. They both died that night. She was afterward very ill with the fever-her life was spared.

Caesar Cranchal, a black man, offered his services to attend the sick, and said, I will not take your money, I will not sell my life for money. It is said he died with the flux.

A black lad, at the Widow Gilpin's, was intrusted with his young Master's keys, on his leaving the city, and transacted his business, with the greatest honesty, and dispatch, having unloaded a vessel for him in the time, and loaded it again.

A woman, that nursed David Bacon, charged with exemplary moderation, and said she would not have any more.It may be said, in vindication of the conduct of those, who discovered ignorance or incapacity in nursing, that it is, in itself, a considerable art, derived from experience, as well as the exercise of the finer feelings of humanity-this experience, nine tenths of those employed, it is probable were wholly strangers to.

We do not recollect such act of humanity from the poor white people, in all the round we have been engaged in. We could mention many other instances of the like nature, but think it needless.

It is unpleasant for us to make these remarks, but justice to our colour, demands it. Mr. Carey pays William Gray and us a compliment; he says, our services and others of their colour, have been very great &c. By naming us, he leaves these others, in the hazardous state of being classed with those who are

[Page 13]

A NARRATIVE, &c. 13

called the "vilest." The few that were discovered to merit public censure, were brought to justice, which ought to have sufficed, without being canvassed over in his "Trifle" of a pamphlet—which causes us to be more particular and endeavour to recall the esteem of the public for our friends, and the people of colour, as far as they may be found worthy; for we conceive, and experience proves it, that an ill name is easier given than taken away. We have many unprovoked enemies, who begrudge us the liberty we enjoy, and are glad to hear of any complaint against our colour, be it just or unjust; in consequence of which we are more earnestly endeavouring all in our power, to warn, rebuke, and exhort our African friends, to keep a con- science void of offence towards God and man; and, at the same time, would not be backward to interfere, when stigmas or oppression appear pointed at, or at- tempted against them, unjustly; and, we are confident, we shall stand justified in the fight of the candid and judicious, for such conduct.

Mr. Carey's first, second, and third editions, are gone forth into the world, and in all probability, have been read by thousands that will never read his fourth- consequently, any alteration he may hereafter make, in the paragraph alluded to, cannot have the desired effect, or atone for the past; therefore we apprehend it necessary to publish our thoughts on the occasion. Had Mr. Carey said, a number of white and black Wretches eagerly seized on the opportunity to extort from the distressed, and some few of both were detected in plundering the sick, it might extenuate, in a great degree, the having made mention of the blacks.

We can assure the public, there were as many white as black people, detected in pilfering, although the number of the latter, employed as nurses, was twenty times as great as the former, and that there is, in our

B

[Page 14]

14 A NARRATIVE, &c.

opinion, as great a proportion of white, as of black, inclined to such practices. It is rather to be admired, that so few instances of pilfering and robbery happened, considering the great opportunities there were for such things: we do not know of more than five black people, suspected of any thing clandestine, out of the great number employed; the people were glad to get any person to assist them-a black was preferred, because it was supposed, they were not so likely to take the disorder, the most worthless were acceptable, so that it would have been no cause of wonder, if twenty causes of complaint occurred, for one that hath. It has been alledged, that many of the sick, were neglected by the nurses; we do not wonder at it, considering their situation, in many instances, up night and day, without any one to relieve them, worn down with fatigue, and want of sleep, they could not in many cases, render that assistance, which was needful: where we visited, the causes of complaint on this score, were not numerous. The case of the nurses, in many instances, were deserving of commiseration, the patient raging and frightful to behold; it has frequently required two persons, to hold them from run[n]ing away, others have made attempts to jump out of a window, in many chambers they were nailed down, and the door was kept locked, to prevent them from running away, or breaking their necks, others lay vomiting blood, and screaming enough to chill them with horror. Thus were many of the nurses circumstanced, alone, until the patient died, then called away to another scene of distress, and thus have been for a week or ten days left to do the best they could without any sufficient rest, many of them having some of their dearest connections sick at the time, and suffering for want, while their husband, wife, father, mother, &c have been engaged in the service of the white people We mention this to shew the difference between this

[Page 15]

A NARRATIVE, &c. 15

and nursing in common cases, we have suffered equally with the whites, our distress hath been very great, but much unknown to the white people. Few have been the whites that paid attention to us while the black were engaged in the other's service. We can assure the public we have taken four and five black people in a day to be buried. In several instances when they have been seized with the sickness while nursing, they have been turned out of the house, and wandering and destitute until taking shelter wherever they could (as many of them would not be admitted to their former homes) they have languished alone and we know of one who even died in a stable. Others acted with more tenderness, when their nurses were taken sick they had proper care taken of them at their houses. We know of two instances of this.

It is even to this day a generally received opinion in this city, that our colour was not so liable to the sickness as the whites. We hope our friends will pardon us for setting this matter in its true state.

The public were informed that in the West-Indies and other places where this terrible malady had been, it was observed the blacks were not affected with it. Happy would it have been for you, and much more so for us, if this observation had been verified by our experience.

When the people of colour had the sickness and died, we were imposed upon and told it was not with the prevailing sickness, until it became too notorious to be denied, then we were told some few died but not many. Thus were our services extorted at the peril of our lives, yet you accuse us of extorting a little money from you.

The bill of mortality for the year 1793, published by Matthew Whitehead, and John Ormrod, clerks, and Joseph Dolby, sexton, will convince any reasonable man that will examine it, that as many coloured people died in proportion as others. In 1792,

B2

[Page 16]

16 A NARRATIVE, &c.

there were 67 of our colour buried, and in 1793 it amounted to 305; thus the burials among us have increased more than fourfold, was not this in a great degree the effects of the services of the unjustly vilified black people?

Perhaps it may be acceptable to the reader to know how we found the sick affected by the sickness; our opportunities of hearing and seeing them have been very great. They were taken with a chill, a headach, a sick stomach, with pains in their limbs and back, this was the way the sickness in general began, but all were not affected alike, some appeared but slightly affected with some of these symptoms, what confirmed us in the opinion of a person being smitten was the colour of their eyes. In some it raged more furiously than in others -- some have languished for seven and ten days, and appeared to get better the day, or some hours before they died, while others were cut off in one, two, or three days, but their complaints were similar. Some lost their reason and raged with all the fury madness could produce, and died in strong convulsions. Others retained their reason to the last, and seemed rather to fall asleep than die. We could not help remarking that the former were of strong passions, and the latter of a mild temper. Numbers died in a kind of dejection, they concluded they must go, (so the phrase for dying was) and therefore in a kind of fixed determined state of mind went off.

It struck our minds with awe, to have application made by those in health, to take charge of them in their sickness, and of their funeral. Such applications have been made to us; many appeared as though they thought they must die, and not live; some have lain on the floor, to be measured for their coffin and grave. A gentleman called one evening, to request a good nurse might be got for him, when he was sick, and to superintend his funeral, and gave particular directions

[Page 17]

A NARRATIVE, &c. 17

how he would have it conducted, it seemed a surprising circumstance, for the man appeared at the time, to be in perfect health, but calling two or three days after to see him, found a woman dead in the house, and the man so far gone, that to administer any thing for his recovery, was needless--he died that evening. We mention this, as an instance of the dejection and despondence, that took hold on the minds of thousands, and are of opinion, it aggravated the case of many, while others who bore up chearfully, got up again, that probably would otherwise have died.

When the mortality came to its greatest stage, it was impossible to procure sufficient assistance, there- fore many whose friends, and relations had left them, died unseen, and unassisted. We have found them in various situations, some laying on the floor, as bloody as if they had been dipt in it, without any appearance of their having had, even a drink of water for their relief; others laying on a bed with their clothes on, as if they had came in fatigued, and lain down to rest; some appeared, as if they had fallen dead on the floor, from the position we found them in.

Truly our task was hard, yet through mercy, we were enabled to go on.

One thing we observed in several instances—when we were called, on the first appearance of the disorder to bleed, the person frequently, on the opening a vein before the operation was near over, felt a change for the better, and expressed a relief in their chief complaints; and we made it a practice to take more blood from them, than is usual in other cafes.; these in a general way recovered; those who did omit bleeding any considerable time, after being taken by the sick- ness, rarely expressed any change they felt in the operation.

We feel a great satisfaction in believing, that we have been useful to the sick, and thus publicly thank

B3

[Page 18]

18 A NARRATIVE, &c.

Doctor Rush, for enabling us to be so. We have bled upwards of eight hundred people, and do declare, we have not received to the value of a dollar and a half, therefor: we were willing to imitate the Doctor's benevolence, who sick or well, kept his house open day and night, to give what assistance he could in this time of trouble.

Several affecting instances occurred, when we were engaged in burying the dead. We have been called to bury some, who when we came, we found alive; at other places we found a parent dead, and none but little innocent babes to be seen, whose ignorance led them to think their parent was asleep; on account of their situation, and their little prattle, we have been so wounded and our feelings so hurt, that we almost concluded to withdraw from our undertaking, but seeing others so backward, we still went on.

An affecting instance.—A woman died, we were sent for to bury her, on our going into the house and taking the coffin in, a dear little innocent accosted us, with, mamma is asleep, don't wake her; but when she saw us put her in the coffin, the distress of the child was so great, that it almost overcame us; when she demanded why we put her mamma in the box? We did not know how to answer her, but committed her to the care of a neighbour, and left her with heavy hearts. In other places where we have been to take the corpse of a parent, and have found a group of little ones alone, some of them in a measure capable of knowing their situation, their cries and the innocent confusion of the little ones, seemed almost too much for human nature to bear. We have picked up little children that were wandering they knew not where, whose (parents were cut off) and taken them to the orphan house, for at this time the dread that prevailed over people's minds was so general, that it was a rare instance to see one neighbour visit another, and

[Page 19]

A NARRATIVE, &c. 19

even friends when they met in the streets were afraid of each other, much less would they admit into their houses the distressed orphan that had been where the sickness was; this extreme seemed in some instances to have the appearance of barbarity; with reluctance we call to mind the many opportunities there were in the power of individuals to be useful to their fellow-men, yet through the terror of the times was omitted. A black man riding through the street, saw a man push a woman out of the house, the woman staggered and fell on her face in the gutter, and was not able to turn herself, the black man thought she was drunk, but observing she was in danger of suffocation alighted and taking the woman up found her perfectly sober, but so far gone with the disorder that she was not able, to help herself; the hard hearted man that threw her down, shut the door and left her—in such a situation, she might have perished in a few minutes: we heard of it, and took her to Bush-hill. Many of the white people, that ought to be patterns for us to follow after, have acted in a manner that would make humanity shudder. We remember an instance of cruelty, which we trust, no black man would be guilty of: two sisters orderly, decent, white women were sick with the fever, one of them recovered so as to come to the door; a neighbouring white man saw her, and in an angry tone asked her if her sister was dead or not? She answered no, upon which he replied, damn her, if she don't die before morning, I will make her die. The poor woman shocked at such an expression, from this monster of a man, made a modest reply, upon which he snatched up a tub of water, and would have dashed it over her, if he had not been prevented by a black man; he then went and took a couple of fowls out of a coop, (which had been given them for nourishment) and threw them into an open alley; he had his with, the poor woman that he would make die,

[Page 20]

A NARRATIVE, &c. 20

died that night. A white man threatened to shoot us, if we passed by his house with a corpse: we buried him three days after.

We have been pained to see the widows come to us, crying and wringing their hands, and in very great distress, on account of their husbands' death; having nobody to help them, they were obliged to come get their husbands buried, their neighbours were afraid to go to their help or to condole to the frailty of human nature, and not to wilful unkindness, or hardness of heart.

Notwithstanding the compliment of Mr. Carey hath paid us, we have found reports spread, of our taking between one, and two hundred beds, from houses where people died; such slandereds as these, who propagate such wilful lies are dangerous, although unworthy notice. We wish if any person hath the least suspicion of us, they would endeavor to bring us to the punishment which such atrocious conduct must deserve; and by this means, the innocent will be cleared from re- proach, and the guilty known.

We shall now conclude with the following old proverb, which we think applicable to those of our colour who exposed their lived in the late afflicting dispensation:—God and a soldier, all men do adore,

In time of war, and not before;

When the war is over, and all things righted,

God is forgotten, and the soldier slighted.

[Page 21]

A NARRATIVE, &c. 21

To MATTHEW CLARKSON, Esq. Mayor of the City of Philadelphia.

SIR,

FOR the personal respect we bear you, and for the satisfaction of the Mayor, we declare, that to the best of our remembrance we had the care of the following beds and no more.-

Two belonging to James Starr we buried; upon taking them up, we found one damaged; the blankets, &c. belonging to it were stolen; it was refused to be accepted of by his son Moses; it was buried again, and remains so for ought we know; the other was return- ed and accepted of.

We buried two belonging to Samuel Fisher, merchant; one of them was taken up by us, to carry a sick person on to Bush-hill, and there left; the other was buried in a grave, under a corpse.

Two beds were buried for Thomas Willing, one six feet deep in his garden, and lime and water thrown upon it; the other was in the Potter's field, and further knowledge of it we have not.

We burned one bed with other furniture, and cloathing belonging to the late Mayor, Samuel Powel, on his farm on the west side of Schuylkill river;—we buried one of his beds.

For --------Dickenson, we buried a bed in a lot of Richard Allen; which we have good cause to believe, was stolen.

One bed was buried for a person in front street, whose name is unknown to us, it was buried in the Potter's field, by a person employed for the purpose; we told him he might take it up again after it had been buried a week, and apply it to his own use, as he

[Page 22]

22 A NARRATIVE, &c.

said he had lately been discharged from the hospital and had none to lay on.

Thomas Leiper's two beds were buried in the Pot- ter's field, and remained there a week, and then taken up by us, for the use of the sick that we took to Bush- hill, and left there.

We buried one for --------Smith, in the Potter's field, which was returned except the furniture, which we believe was stolen.

One other we buried for ------Davis, in Vine street, it was buried near Schuylkill, and we believe continues so.

A bed from ------Guests in Second street, was buried in the Potter's field, and is there yet, for any thing we know.

One bed we buried in the Presbyterian burial ground the corner of Pine and Fourth streets, and we believe— was taken up by the owner, Thomas Mitchel.

------Millegan in Second street, had a bed buried by us in the Potter's field—we have no further knowledge of it.

This is a true state of matters respecting the beds, as far as we were concerned, we never undertook the charge of more than their burial, knowing they were liable to be taken away by evil minded persons. We think it beneath the dignity of an honest man, (although— injured in his reputation by wicked and envious persons) to vindicate or support his character, by an oath or legal affirmation; we fear not our enemies, let them come forward with their charges, we will not flinch, and if they can fix any crime upon us, we refuse not to suffer.

SIR,

You have cause to believe our lives were endangered in more cases than one, in the time of the late mortality, and that we were so discouraged, that had it not been for your persuasion, we would have relin-

[Page 23]

A NARRATIVE, &c. 23

-quished our disagreable and dangerous employment- and we hope there is no impropriety in soliciting a certificate of your approbation of our conduct, so far as it hath come to your knowledge.

With an affectionate regard and esteem,

We are your friends,

ABSALOM JONES.

RICHARD ALLEN.

January 7th 1794.

_______________________________________________________________

HAVING, during the prevalence of the late malignant disorder, had almost daily opportunities of seeing the conduct of Absalom Jones and Richard Allen, and the people employed by them, to bury the dead—I with cheerfulness give this testimony of my approbation of their proceedings, as far as the same came under my notice. Their diligence, attention and decency of deportment, afforded me, at the time, much satisfaction.

MATTHEW CLARKSON, Mayor.

Philadelphia, January 23, 1794.

_______________________________________________________________

An Address to those who keep Slaves, and approve the practice.

THE judicious part of mankind will think it un-reasonable, that a superior good conduct is looked for, from our race, by those who stigmatize us as men, whose baseness is incurable, and may therefore be held in a state of servitude, that a merciful man would not doom a beast to; yet you try what you can to prevent our rising from the state of barbarism, you represent us to be in, but we can tell you, from a degree of experience, that a black man, although reduced to the most abject state human nature is capable of, short of real madness, can think, reflect, and feel injuries, although it may not be with the same degree of keen resentment and revenge, that you who have been and are our great oppressors, would manifest if reduced to the pitiable condition of a slave…

Note: To read further, see the original document or this transcipt source which was very helpful to creating the above transcription: "A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People, during the late awful Calamity in Philadelphia, in the year 1793," Molly O'Hagan Hardy, contributor, TAPAS Project, Northeastern University, accessed September 18, 2024, https://tapasproject.org/proceedingsofblackpeople/files/narrative-proceedings-black-people-during-late-awful-calamity.

Moses Brown's [cursive handwriting]

A

NARRATIVE

OF THE

PROCEEDINGS

OF THE

BLACK PEOPLE

DURING THE LATE

Awful Calamity in Philadelphia,

IN THE YEAR 1793 :

AND

A REFUTATION

OF SOME CENSURES,

Thrown upon them in some late Publication.

By A.J. and R.A.

PHILADELPHIA : PRINTED FOR THE AUTHORS,

BY WILLIAM W. WOODWARD, AT FRANKLIN’S HEAD,

NO. 41, CHESNUT-STREET.

1794

[Page 2]

No. 54

District of Pennsylvania, to wit.

BE IT REMEMBERED, That on the twenty-third day of January, in the eighteenth year of the Independence of the United States of America, Absalom Jones and Richard Allen, both of the said District, have deposited in this office, the title of a book, the right whereof they claim as authors and proprietors, in the words following, to wit : “ A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People, during the late awful Calamity in Philadelphia, in the year 1793: and a Refutation of some Censures thrown upon then in some late Publications. By A. J. & R.A.” In conformity to the act of the Congress of the United States, intitled, “An act for the encouragement of learning, by securing the copies of maps, charts, and books, to the authors and proprietors of such copies, during the times therein mentioned.”

Samuel Caldwell,

Clerk of the District of Pennsylvania.

[Page 3]

A NARRATIVE, &c.

IN consequence of a partial representation of the conduct of the people who were employed to nurse the sick, in the late calamitous state of the city of Philadelphia, we are solicited, by a number of those who feel themselves injured thereby, and by the ad- vice of several respectable citizens, to step forward and declare facts as they really were; seeing that from our situation, on account of the charge we took upon us, we had it more fully and generally in our power, to know and observe the conduct and behavior of those that were so employed.

Early in September, a solicitation appeared in the public papers, to the people of colour to come forward and assist the distressed, perishing, and neglected sick; with a kind of assurance, that people of our colour were not liable to take the infection. Upon which we and a few others met and consulted how to act on so truly alarming and melancholy an occasion. After some conversation, we found a freedom to go forth, confiding in him who can preserve in the midst of a burning fiery furnace, sensible that it was our duty to do all the good we could to our suffering fellow mor- tals. We set out to see where we could be useful. The first we visited was a man in Emfley's alley, who was dying, and his wife lay dead at the time in the house, there were none to assist but two poor helpless children. We administered what relief we could, and applied to the overseers of the poor to have the woman buried. We visited upwards of twenty families that

A 2

[Page 4]

4 A NARRATIVE,&c.

day-they were scenes of woe indeed! The Lord was pleased to strengthen us, and remove all fear from us, and disposed our hearts to be as useful as possible.

In order the better to regulate our conduct, we called on the mayor next day, to consult with him how to proceed, so as to be most useful. The first object he recommended was a strict attention to the sick, and the procuring of nurses. This was attended to by Absalom Jones and William Gray; and, in order that the distressed might know where to apply, the mayor advertised the public that upon application to them they would be supplied. Soon after, the mortality increasing, the difficulty of getting a corpse taken away, was such, that few were willing to do it, when offered great rewards. The black people were looked to. We then offered our Services in the public papers, by advertising that we would remove the dead and procure nurses. Our services were the production of real sensibility; - we sought not fee nor reward, until the increase of the disorder rendered our labour so arduous that we were not adequate to the service we had assumed. The mortality increasing rapidly, obliged us to call in the assistance of five* hired men, in the awful discharge of interring the dead. They, with great reluctance, were prevailed upon to join us. It was very uncommon, at this time, to find any one that would go near, much more, handle, a sick or dead person.

Mr. Carey, in page 106 of his third edition, has observed, that, "for the honor of human nature, it ought to be recorded, that some of the convicts in the gaol, a part of the term of whose confinement had been remitted as a reward for their peaceable, orderly behavior, voluntarily offered themselves as nurses to attend the sick at Bush-hill; and have, in that capacity, conducted themselves with great fidelity, &c. Here

*Two of whom were Richard Allen’s brothers.

[Page 5]

A NARRATIVE, &c. 5

it ought to be remarked, (although Mr. Carey hath not done it) that two thirds of the persons, who rendered these essential services, were people of colour, who, on the application of the elders of the African church, (who met to consider what they could do for the help of the sick) were liberated, on condition of their doing the duty of nurses at the hospital at Bush- hill; which they as voluntarily accepted to do, as they did faithfully discharge, this severe and disagreeable duty.—May the Lord reward them, both temporally and spiritually.

When the sickness became general, and several of the physicians died, and most of the survivors were exhausted by sickness or fatigue; that good man, Doctor Rush, called us more immediately to attend upon the sick, knowing we could both bleed; he told us we could increase our utility, by attending to his instructions, and accordingly directed us where to procure medicine duly prepared, with proper directions how to administer them, and at what stages of the disorder to bleed; and when we found ourselves incapable of judging what was proper to be done, to apply to him, and he would, if able, attend them himself, or send Edward Fisher, his pupil, which he often did; and Mr. Fisher manifested his humanity, by an affectionate attention for their relief.– This has been no small satisfaction to us; for, we think, that when a physician was not attainable, we have been the instruments, in the hand of God, for saving the lives of some hundreds of our suffering fellow mortals.

We feel ourselves sensibly aggrieved by the censorious epithets of many, who did not render the least assistance in the time of necessity, yet are liberal of their censure of us, for the prices paid for our services, when no one knew bow to make a proposal to any one they wanted to assist them. At first we made no charge, but left it to those we served in removing their dead,

A3

[Page 6]

6 A NARRATIVE, &c.

to give what they thought fit - we set no price, until the reward was fixed by those we had served. After paying the people we had to assist us, our compensation is much less than many will believe.

We do assure the public, that all the money we have received, for burying, and for coffins which we our- selves purchased and procured, has not defrayed the expence of wages which we had to pay to those whom we employed to assist us. The following statement is accurately made:

CASH RECEIVED.

The whole amount of Cash we received for burying the dead, and for burying beds, is, - -£233 10 4

CASH PAID.

For coffins, for which we have received nothing - £33 0 0

For the hire of five men, 3 of them 70 days each, and the other two, 63 days each, at 22s 6 per day, - - - 378 0 0

411 0 0

Debts due us, for which we expect but little, - £110 0 0

From this statement, for the truth of which we solemnly vouch, it is evident, and we sensibly feel the operation of the fact, that we are out of pocket, - - - - £ 177 9 8

Besides the costs of hearses, the maintenance of our families for 70 days, (being the period of our labours) and the support of the five hired men, during the respective times of their being employed; which expences, together with sundry gifts we occasionally made to poor family, might reasonably and intro-

[Page 7]

A NARRATIVE, &c. 7

-duced, to show our actual situation with regard to pro- fit-but it is enough to exhibit to the public, from the above specified items, of Cash paid and Cash received, without taking into view the other expences, that, by the employment we were engaged in, we have lost £177 9 8. But, if the other expences, which we have actually paid, are added to that sum, how much then may we not say we have suffered! We leave the public to judge.

It may possibly appear strange to some who know how constantly we were employed, that we should have received no more Cash than £233 10 4. But we repeat our assurance, that this is the fact, and we add another, which will serve the better to explain it: We have buried several hundreds of poor persons and strangers, for which service we have never received, nor never asked any compensation.

We feel ourselves hurt most by a partial, censorious paragraph, in Mr. Carey’s second edition of his account of the sickness, &c. in Philadelphia; pages 76 and 77, where he asperses the blacks alone, for having taken the advantage of the distressed situation of the people. That some extravagant prices were paid, we admit; but how came they to be demanded? the reason is plain. It was with difficulty persons could be had to supply the wants of the sick, as nurses;-applications became more and more numerous, the consequence was, when we procured them at six dollars per week, and called upon them to go where they were wanted, we found they were gone elsewhere; here was a disappointment; upon enquiring the cause, we found, they had been allured away by others who of- fered greater wages, until they got from two to four dollars per day. We had no restraint upon the peo- ple. It was natural for people in low circumstances to accept a voluntary, bounteous reward; especially under the loathsomness of many of the sick, when na-

[Page 8]

8 A NARRATIVE, &c.

-ture shuddered at the thoughts of the infection, and the talk assigned was aggravated by lunacy, and being left much alone with them. Had Mr. Carey been so- licited to such an undertaking, for hire, Query, "what would he have demanded? but Mr. Carey, although chosen a member of that band of worthies who have so eminently distinguished themselves by their labours, for the relief of the sick and helpless-yet, quickly after his election, left them to struggle with their arduous and hazardous talk, by leaving the city. 'Tis true Mr. Carey was no hireling, and had a right to flee, and upon his return, to plead the cause of those who fled; yet, we think, he was wrong in giving so partial and injurious an account of the black nurses; if they have taken advantage of the public distress? Is it anymore than he hath done of its desire for information. We believe he has made more money by the sale of his "scraps" than a dozen of the greatest extortioners among the black nurses. The great prices paid did not escape the observation of that worthy and vigilant magistrate, Mathew Clarkson, mayor of the city, and president of the committee-he sent for us, and requested we would use our influence, to lessen the wages of the nurses, but on informing him the cause, i. e. that of the people over- bidding one another, it was concluded unnecessary to attempt any thing on that head; therefore it was left to the people concerned. That there were some few black people guilty of plundering the distressed, we acknowledge; but in that they only are pointed out, and made mention of, we esteem partial and injurious; we know as many whites who were guilty of it; but this is looked over, while the blacks are held up to censure.—Is it a greater crime for a black to pilfer, than for a white to privateer?

We wish not to offend, but when an unprovoked attempt is made, to make us blacker than we are, it be- comes less necessary to be over cautious on that ac-

[Page 9]

A NARRATIVE,&c. 9

- count; therefore we shall take the liberty to tell of the conduct of some of the whites.

We know six pounds was demanded by, and paid, to a white woman, for putting a corpse into a coffin; and forty dollars was demanded, and paid, to four white men, for bringing it down the stairs.

Mr. and Mrs. Taylor both died in one night; a white woman had the care of them; after they were dead she called on Jacob Servoss, esq. for her pay, demanding six pounds for laying them out; upon seeing a bundle with her, he suspected she had pilfered; on searching her, Mr. Taylor's buckles were found in her pocket, with other things.

An elderly lady, Mrs. Malony, was given into the care of a white woman, she died, we were called to remove the corpse, when we came the woman was lay- ing so drunk that she did not know what we were do- ing, but we know she had one of Mrs. Malony's rings on her finger, and another in her pocket.

Mr. Carey tells us, Bush-hill exhibited as wretched a picture of human misery, as ever existed. A profli- gate abandoned set of nurses and attendants (hardly any of good charater could at that time be procured,) rioted on the provisions and comforts, prepared for the sick, who (unless at the hours when the doctors attend- ed) were left almost entirely destitute of every assist- ance. The dying and dead were indiscriminately mingled together. The ordure and other evacuations of the sick, were allowed to remain in the most offen- sive state imaginable. Not the smallest appearance of order or regularity existed. It was in fact a great hu- man slaughter house, where numerous victims were immolated at the altar of intemperance.

It is unpleasant to point out the bad and unfeeling conduct of any colour, yet the defence we have under- taken obliges us to remark, that although "hardly any of good character at that time could be procured" yet only two black women were at this time in the hospi-

[Page 10]

10 A NARRATIVE, &c.

-tal, and they were retained and the others discharged, when it was reduced to order and good government.

The bad consequences many of our colour apprehend from a partial relation of our conduct are, that it will prejudice the minds of the people in general against us —because it is impossible that one individual, can have knowledge of all, therefore at some future day, when some of the most virtuous, that were upon most praiseworthy motives, induced to serve the sick, may fall in- to the service of a family that are strangers to him, or her, and it is discovered that it is one of those stigmatised wretches, what may we suppose will be the consequence? Is it not reasonable to think the person will be abhored, despised, and perhaps dismissed from employment, to their great disadvantage, would not this be hard? and have we not therefore sufficient reason to seek for-redress? We can with certainty assure the public that we have seen more humanity, more real sensibility from the poor blacks, than from the poor whites. When many of the former, of their own accord rendered services where extreme necessity called for it, the general part of the poor white people were so dismayed, that instead of attempting to be useful, they in a manner hid themselves—a remarkable instance of this—A poor aflicted dying man, stood at his chamber window, praying and beseeching every one that passed by, to help him to a drink of water; a number of white people passed, and instead of being moved by the poor man's distress, they hurried as fast as they could out of the sound of his cries-until at length a gentleman, who seemed to be a foreigner came up, he could not pass by, but had not resolution enough to go into the house, he held eight dollars in his hand, and offered it to several as a reward for giving the poor man a drink of water, but was refused by every one, until a poor black man came up, the gentleman offered the eight dollars to him, if he would relieve

[Page 11]

A NARRATIVE, &c. 11

the poor man with a little water, "Master" replied the good natured fellow, "I will supply the gentleman with water, but surely I will not take your money for it" nor could he be prevailed upon to accept his bounty: he went in, supplied the poor object with water, and rendered him every service he could.

A poor black man, named Sampson, went constantly from house to house where distress was, and no assistance without fee or reward; he was smote with the disorder, and died, after his death his family were negleted by those he had served.

Sarah Bass, a poor black widow, gave all the assistance she could, in several families, for which she did not receive any thing; and when any thing was offered her, she left it to the option of those she served.

A woman of our colour, nursed Richard Mason and son, when they died, Richard's widow considering the risk the poor woman had run, and from observing the fears that sometimes relied on her mind, expected she would have demanded something considerable, but upon asking what she demanded, her reply was half a dollar per day. Mrs. Mason, intimated it was not sufficient for her attendance, she replied it was enough for what she had done, and would take no more. Mrs. Mason's feelings were such, that she settled an annuity of six pounds a year, on her, for life. Her name is Mary Scott.

An elderly black woman nursed --------with great diligence and attention; when recovered he asked what he must give for her services—she replied "a din- ner master on a cold winter's day," and thus she went from place to place rendering every service in her pow- er without an eye to reward.

A young black woman, was requested to attend one night upon a white man and his wife, who were very ill, no other person could be had;—great wages were offered her—she replied, I will not go for money, if I

[Page 12]

12 A NARRATIVE, &c.

go for money God will see it, and may be make me take the disorder and die, but if I go, and take no money, he may spare my life. She went about nine o'clock, and found them both on the floor; she could procure no candle or other light, but staid with them about two hours, and then left them. They both died that night. She was afterward very ill with the fever-her life was spared.

Caesar Cranchal, a black man, offered his services to attend the sick, and said, I will not take your money, I will not sell my life for money. It is said he died with the flux.

A black lad, at the Widow Gilpin's, was intrusted with his young Master's keys, on his leaving the city, and transacted his business, with the greatest honesty, and dispatch, having unloaded a vessel for him in the time, and loaded it again.

A woman, that nursed David Bacon, charged with exemplary moderation, and said she would not have any more.It may be said, in vindication of the conduct of those, who discovered ignorance or incapacity in nursing, that it is, in itself, a considerable art, derived from experience, as well as the exercise of the finer feelings of humanity-this experience, nine tenths of those employed, it is probable were wholly strangers to.

We do not recollect such act of humanity from the poor white people, in all the round we have been engaged in. We could mention many other instances of the like nature, but think it needless.

It is unpleasant for us to make these remarks, but justice to our colour, demands it. Mr. Carey pays William Gray and us a compliment; he says, our services and others of their colour, have been very great &c. By naming us, he leaves these others, in the hazardous state of being classed with those who are

[Page 13]

A NARRATIVE, &c. 13

called the "vilest." The few that were discovered to merit public censure, were brought to justice, which ought to have sufficed, without being canvassed over in his "Trifle" of a pamphlet—which causes us to be more particular and endeavour to recall the esteem of the public for our friends, and the people of colour, as far as they may be found worthy; for we conceive, and experience proves it, that an ill name is easier given than taken away. We have many unprovoked enemies, who begrudge us the liberty we enjoy, and are glad to hear of any complaint against our colour, be it just or unjust; in consequence of which we are more earnestly endeavouring all in our power, to warn, rebuke, and exhort our African friends, to keep a con- science void of offence towards God and man; and, at the same time, would not be backward to interfere, when stigmas or oppression appear pointed at, or at- tempted against them, unjustly; and, we are confident, we shall stand justified in the fight of the candid and judicious, for such conduct.

Mr. Carey's first, second, and third editions, are gone forth into the world, and in all probability, have been read by thousands that will never read his fourth- consequently, any alteration he may hereafter make, in the paragraph alluded to, cannot have the desired effect, or atone for the past; therefore we apprehend it necessary to publish our thoughts on the occasion. Had Mr. Carey said, a number of white and black Wretches eagerly seized on the opportunity to extort from the distressed, and some few of both were detected in plundering the sick, it might extenuate, in a great degree, the having made mention of the blacks.

We can assure the public, there were as many white as black people, detected in pilfering, although the number of the latter, employed as nurses, was twenty times as great as the former, and that there is, in our

B

[Page 14]

14 A NARRATIVE, &c.

opinion, as great a proportion of white, as of black, inclined to such practices. It is rather to be admired, that so few instances of pilfering and robbery happened, considering the great opportunities there were for such things: we do not know of more than five black people, suspected of any thing clandestine, out of the great number employed; the people were glad to get any person to assist them-a black was preferred, because it was supposed, they were not so likely to take the disorder, the most worthless were acceptable, so that it would have been no cause of wonder, if twenty causes of complaint occurred, for one that hath. It has been alledged, that many of the sick, were neglected by the nurses; we do not wonder at it, considering their situation, in many instances, up night and day, without any one to relieve them, worn down with fatigue, and want of sleep, they could not in many cases, render that assistance, which was needful: where we visited, the causes of complaint on this score, were not numerous. The case of the nurses, in many instances, were deserving of commiseration, the patient raging and frightful to behold; it has frequently required two persons, to hold them from run[n]ing away, others have made attempts to jump out of a window, in many chambers they were nailed down, and the door was kept locked, to prevent them from running away, or breaking their necks, others lay vomiting blood, and screaming enough to chill them with horror. Thus were many of the nurses circumstanced, alone, until the patient died, then called away to another scene of distress, and thus have been for a week or ten days left to do the best they could without any sufficient rest, many of them having some of their dearest connections sick at the time, and suffering for want, while their husband, wife, father, mother, &c have been engaged in the service of the white people We mention this to shew the difference between this

[Page 15]

A NARRATIVE, &c. 15

and nursing in common cases, we have suffered equally with the whites, our distress hath been very great, but much unknown to the white people. Few have been the whites that paid attention to us while the black were engaged in the other's service. We can assure the public we have taken four and five black people in a day to be buried. In several instances when they have been seized with the sickness while nursing, they have been turned out of the house, and wandering and destitute until taking shelter wherever they could (as many of them would not be admitted to their former homes) they have languished alone and we know of one who even died in a stable. Others acted with more tenderness, when their nurses were taken sick they had proper care taken of them at their houses. We know of two instances of this.

It is even to this day a generally received opinion in this city, that our colour was not so liable to the sickness as the whites. We hope our friends will pardon us for setting this matter in its true state.

The public were informed that in the West-Indies and other places where this terrible malady had been, it was observed the blacks were not affected with it. Happy would it have been for you, and much more so for us, if this observation had been verified by our experience.

When the people of colour had the sickness and died, we were imposed upon and told it was not with the prevailing sickness, until it became too notorious to be denied, then we were told some few died but not many. Thus were our services extorted at the peril of our lives, yet you accuse us of extorting a little money from you.

The bill of mortality for the year 1793, published by Matthew Whitehead, and John Ormrod, clerks, and Joseph Dolby, sexton, will convince any reasonable man that will examine it, that as many coloured people died in proportion as others. In 1792,

B2

[Page 16]

16 A NARRATIVE, &c.

there were 67 of our colour buried, and in 1793 it amounted to 305; thus the burials among us have increased more than fourfold, was not this in a great degree the effects of the services of the unjustly vilified black people?

Perhaps it may be acceptable to the reader to know how we found the sick affected by the sickness; our opportunities of hearing and seeing them have been very great. They were taken with a chill, a headach, a sick stomach, with pains in their limbs and back, this was the way the sickness in general began, but all were not affected alike, some appeared but slightly affected with some of these symptoms, what confirmed us in the opinion of a person being smitten was the colour of their eyes. In some it raged more furiously than in others -- some have languished for seven and ten days, and appeared to get better the day, or some hours before they died, while others were cut off in one, two, or three days, but their complaints were similar. Some lost their reason and raged with all the fury madness could produce, and died in strong convulsions. Others retained their reason to the last, and seemed rather to fall asleep than die. We could not help remarking that the former were of strong passions, and the latter of a mild temper. Numbers died in a kind of dejection, they concluded they must go, (so the phrase for dying was) and therefore in a kind of fixed determined state of mind went off.

It struck our minds with awe, to have application made by those in health, to take charge of them in their sickness, and of their funeral. Such applications have been made to us; many appeared as though they thought they must die, and not live; some have lain on the floor, to be measured for their coffin and grave. A gentleman called one evening, to request a good nurse might be got for him, when he was sick, and to superintend his funeral, and gave particular directions

[Page 17]

A NARRATIVE, &c. 17

how he would have it conducted, it seemed a surprising circumstance, for the man appeared at the time, to be in perfect health, but calling two or three days after to see him, found a woman dead in the house, and the man so far gone, that to administer any thing for his recovery, was needless--he died that evening. We mention this, as an instance of the dejection and despondence, that took hold on the minds of thousands, and are of opinion, it aggravated the case of many, while others who bore up chearfully, got up again, that probably would otherwise have died.

When the mortality came to its greatest stage, it was impossible to procure sufficient assistance, there- fore many whose friends, and relations had left them, died unseen, and unassisted. We have found them in various situations, some laying on the floor, as bloody as if they had been dipt in it, without any appearance of their having had, even a drink of water for their relief; others laying on a bed with their clothes on, as if they had came in fatigued, and lain down to rest; some appeared, as if they had fallen dead on the floor, from the position we found them in.

Truly our task was hard, yet through mercy, we were enabled to go on.

One thing we observed in several instances—when we were called, on the first appearance of the disorder to bleed, the person frequently, on the opening a vein before the operation was near over, felt a change for the better, and expressed a relief in their chief complaints; and we made it a practice to take more blood from them, than is usual in other cafes.; these in a general way recovered; those who did omit bleeding any considerable time, after being taken by the sick- ness, rarely expressed any change they felt in the operation.

We feel a great satisfaction in believing, that we have been useful to the sick, and thus publicly thank

B3

[Page 18]

18 A NARRATIVE, &c.

Doctor Rush, for enabling us to be so. We have bled upwards of eight hundred people, and do declare, we have not received to the value of a dollar and a half, therefor: we were willing to imitate the Doctor's benevolence, who sick or well, kept his house open day and night, to give what assistance he could in this time of trouble.

Several affecting instances occurred, when we were engaged in burying the dead. We have been called to bury some, who when we came, we found alive; at other places we found a parent dead, and none but little innocent babes to be seen, whose ignorance led them to think their parent was asleep; on account of their situation, and their little prattle, we have been so wounded and our feelings so hurt, that we almost concluded to withdraw from our undertaking, but seeing others so backward, we still went on.

An affecting instance.—A woman died, we were sent for to bury her, on our going into the house and taking the coffin in, a dear little innocent accosted us, with, mamma is asleep, don't wake her; but when she saw us put her in the coffin, the distress of the child was so great, that it almost overcame us; when she demanded why we put her mamma in the box? We did not know how to answer her, but committed her to the care of a neighbour, and left her with heavy hearts. In other places where we have been to take the corpse of a parent, and have found a group of little ones alone, some of them in a measure capable of knowing their situation, their cries and the innocent confusion of the little ones, seemed almost too much for human nature to bear. We have picked up little children that were wandering they knew not where, whose (parents were cut off) and taken them to the orphan house, for at this time the dread that prevailed over people's minds was so general, that it was a rare instance to see one neighbour visit another, and

[Page 19]

A NARRATIVE, &c. 19

even friends when they met in the streets were afraid of each other, much less would they admit into their houses the distressed orphan that had been where the sickness was; this extreme seemed in some instances to have the appearance of barbarity; with reluctance we call to mind the many opportunities there were in the power of individuals to be useful to their fellow-men, yet through the terror of the times was omitted. A black man riding through the street, saw a man push a woman out of the house, the woman staggered and fell on her face in the gutter, and was not able to turn herself, the black man thought she was drunk, but observing she was in danger of suffocation alighted and taking the woman up found her perfectly sober, but so far gone with the disorder that she was not able, to help herself; the hard hearted man that threw her down, shut the door and left her—in such a situation, she might have perished in a few minutes: we heard of it, and took her to Bush-hill. Many of the white people, that ought to be patterns for us to follow after, have acted in a manner that would make humanity shudder. We remember an instance of cruelty, which we trust, no black man would be guilty of: two sisters orderly, decent, white women were sick with the fever, one of them recovered so as to come to the door; a neighbouring white man saw her, and in an angry tone asked her if her sister was dead or not? She answered no, upon which he replied, damn her, if she don't die before morning, I will make her die. The poor woman shocked at such an expression, from this monster of a man, made a modest reply, upon which he snatched up a tub of water, and would have dashed it over her, if he had not been prevented by a black man; he then went and took a couple of fowls out of a coop, (which had been given them for nourishment) and threw them into an open alley; he had his with, the poor woman that he would make die,

[Page 20]

A NARRATIVE, &c. 20

died that night. A white man threatened to shoot us, if we passed by his house with a corpse: we buried him three days after.

We have been pained to see the widows come to us, crying and wringing their hands, and in very great distress, on account of their husbands' death; having nobody to help them, they were obliged to come get their husbands buried, their neighbours were afraid to go to their help or to condole to the frailty of human nature, and not to wilful unkindness, or hardness of heart.

Notwithstanding the compliment of Mr. Carey hath paid us, we have found reports spread, of our taking between one, and two hundred beds, from houses where people died; such slandereds as these, who propagate such wilful lies are dangerous, although unworthy notice. We wish if any person hath the least suspicion of us, they would endeavor to bring us to the punishment which such atrocious conduct must deserve; and by this means, the innocent will be cleared from re- proach, and the guilty known.

We shall now conclude with the following old proverb, which we think applicable to those of our colour who exposed their lived in the late afflicting dispensation:—God and a soldier, all men do adore,

In time of war, and not before;

When the war is over, and all things righted,

God is forgotten, and the soldier slighted.

[Page 21]

A NARRATIVE, &c. 21

To MATTHEW CLARKSON, Esq. Mayor of the City of Philadelphia.

SIR,

FOR the personal respect we bear you, and for the satisfaction of the Mayor, we declare, that to the best of our remembrance we had the care of the following beds and no more.-

Two belonging to James Starr we buried; upon taking them up, we found one damaged; the blankets, &c. belonging to it were stolen; it was refused to be accepted of by his son Moses; it was buried again, and remains so for ought we know; the other was return- ed and accepted of.

We buried two belonging to Samuel Fisher, merchant; one of them was taken up by us, to carry a sick person on to Bush-hill, and there left; the other was buried in a grave, under a corpse.

Two beds were buried for Thomas Willing, one six feet deep in his garden, and lime and water thrown upon it; the other was in the Potter's field, and further knowledge of it we have not.