Last updated: July 9, 2024

Article

Improving Accessibility at Yosemite National Park

Yosemite National Park

By Ellie Kaplan/NPS Park History Program

Have you ever complained when you felt frustrated or excluded? Have you ever thought about complaining as a type of activism? Since the 1970s, disabled visitors have used complaints to improve access at Yosemite National Park for everyone.

The Power of Complaints

After a 1993 vacation, Marguerite filed a complaint with Yosemite:

"I was refused participation in horseback-riding because of my blindness. I am an experienced rider. I feel employees should be better educated about the abilities of the disabled and encouraged to maximize flexibility to enhance everyone’s enjoyment of the park."

Over the years, hundreds of visitors have submitted feedback forms and talked to park employees to demand greater access. Laws like the Architectural Barriers Act of 1968 and the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 (as amended) outlawed discrimination against disabled Americans within federally-funded programs and places. But implementation of the laws was slow. Ordinary visitors' complaints pressured park staff to prioritize access in their budgets and planning.

The assumption that people with disabilities would not visit the park was an early barrier to improving access. Some people believed accommodations were not worth the costs. Correspondence and conversations with disabled visitors disproved such thinking. They moved Yosemite to invest in accessibility.

Yosemite National Park Archives

The Golden Access Pass

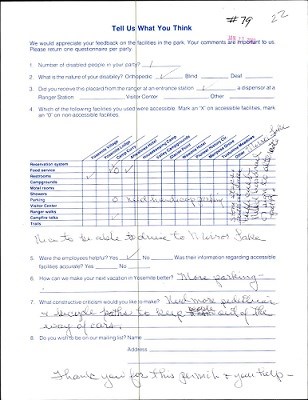

One way that disabled visitors expressed their opinions was through the "Handicap Placard Survey." Upon entering the park, visitors with a Golden Access Passport received the survey. The Golden Access Passport was created in 1981. It provided disabled US citizens and permanent residents with a lifetime free pass to all NPS units and federal lands. Renamed the Interagency Access Pass in 2004, the pass is still available today.

According to the form, the NPS designed the placard survey to get feedback from blind, D/deaf,1 and "orthopedically" disabled visitors. The survey asked for constructive criticism on how to improve the park experience. It also included a chart of popular areas where respondents could mark the accessible and non-accessible facilities. The chart included places like restrooms, campgrounds, and parking lots. The survey received many responses on the park experience, primarily from visitors with physical disabilities. This limited the diversity of perspectives, because it did not represent the range of conditions with which disabled people may live.

Accurate Communication

One complainant named Walter wrote a letter to NPS Director George B. Hartzog, Jr. in the early 1970s. “The National Park Guide for the Handicapped,” Walter pointed out, falsely described certain facilities as accessible. In actuality, narrow bathrooms and the absence of ramps excluded people in wheelchairs.

Over twenty years later, in 1997, another visitor named Candy encountered similar problems with inaccuracies. She shared them with the Yosemite Accessibility Coordinator. “It is extremely frustrating,” she wrote, “to go to an attraction or facility that is billed as ‘accessible’ only to find it very inaccessible.” Candy urged Yosemite to regularly inform disabled visitors about changes in park access.

Inaccurate and outdated information was a recurring complaint among visitors with disabilities. Many visitors asked for more widely available information. They sought clearer maps and signs throughout the park. They also wanted employees to be more proactive about offering accessibility information.

Expand Types of Access

Gail, a visitor to Yosemite, complained to the Concessions Management Specialist in 2002:

"A disabled person such as myself cannot easily get up and down the steps of these public buses due to their absurd height off the ground. I actually fell getting off the last bus because the lowest step was at least twelve to fifteen inches from the ground… I’ve had to give up many activities due to my disability, but I never thought public transportation in our national parks, supported with my tax dollars, would be off-limits to me."

Disabled visitors were quick to remind Yosemite that there is no “one size fits all” when it comes to access. The needs of a wheelchair user differ from the needs of a person who walks with limited mobility, which differ from the needs of a blind visitor, and so on. Visitors also expressed the importance of access everywhere, rather than only in designated areas.

Yosemite National Park Archives. 2003.

Changing Attitudes

A beachgoer named Sylvia had a frustrating experience when trying to find accessible beach parking during a 1993 trip. After the trip, she called the Yosemite Access Coordinator Don Fox to complain. Fox relayed the message to the rangers. He explained, “Her primary concern was the insensitive way that she was treated by park employees, their ‘lack of imagination, common decency, and unwillingness to cooperate,’ on what she reminded me, ‘is the law’ (Americans with Disabilities Act) to provide parking for people with disabilities."

Visitors with disabilities encountered access barriers in the built environment. But they also faced barriers in the attitudes of some nondisabled park staff. Negative interactions at Yosemite left visitors feeling frustrated or humiliated. Their complaints remind us that inaccessibility takes an emotional toll as much as a physical one. As visitors explained in their critiques, access was not an act of charity but a civil right. To address these issues, Yosemite has led staff workshops about disabilities since the 1970s. These trainings have helped shift employees' ideas about disability and access.

Disabled Perspectives

Complaints at Yosemite have been part of a broader cultural shift. It brought more awareness to the rights of people with disabilities across public spaces. This shift in thinking also put responsibility on the NPS to ensure that disabled visitors could enjoy the park alongside their nondisabled peers.

“Please have each and every member of the planning committee spend one day and night in a wheelchair using nothing but the park facilities,” a visitor named Evelyn urged in an undated letter. “I think they might understand a little better.”

Disabled visitors used complaints to provide their perspectives on the park based on their lived experiences with a disability. Yosemite and the National Park Service began hiring more employees with disabilities in the 1970s. But most staff members remained nondisabled. Thus, it was crucial to learn directly from disabled visitors how the park could apply access in practice, and not just in theory.

Yosemite National Park Archives. 2003.

Gratitude

On her placard survey in 1990, Edith admired the progress on access thus far: "I wish to praise the people planning and creating the accessibilities. Keep up the good work!!!"

"Having paved walks to Lower Yosemite & Bridal Veil Falls and making it the whole way in a chair was the high point of our trip. Thank you!" shared Judy in her 1995 survey.

Disabled visitors used compliments along with complaints to improve access. Many respondents thanked and encouraged Yosemite to continue expanding access. Complaints are not only a means of showing frustration. They also represent hope. People who submit complaints have hope that things can get better. Disabled visitors to Yosemite shared their experiences and ideas with park staff to improve the park for themselves and millions of other people with disabilities. Their efforts show the power of ordinary people and park employees working together to create a better park for all.

This article was written by Ellie Kaplan, MA, National Council for Preservation Education Intern, with the National Park Service Park History Program. 2023.

End Note

1 The capitalization of the term “deaf” matters when writing Deaf history. Deaf, with a capital D, refers to people with a shared Deaf culture, based on a common language (American Sign Language), history, and set of values. In contrast, deaf, with a lowercase d, refers to the medical condition of not hearing. Different individuals may identify as Deaf or deaf. Scholars have taken to using the nomenclature “D/deaf” to be inclusive of both identities.

Sources

Facilities Management Records, 1914-2010. YOSE 223003. Series 3, subseries O, box 1 and 2. Yosemite National Park Archives. El Portal, CA.