Last updated: August 26, 2020

Article

Hyde Park Interior Design Sources: Codman’s Eye

Metropolitan Museum of Art

In the construction of Gilded Age country houses, such prominent architects of the period as Richard Morris Hunt (1827-1895) and the firm of McKim, Mead & White (active 1879-ca. 1955), generally collaborated with a relatively small group of interior decorators, most frequently either Baumgarten & Co., Herter Brothers, L. Marcotte, & Co., Pottier & Stymus, Ogden Codman or one of the Paris-based international firms such as Allard & Sons. On certain occasions these collaborations might also entail more than one decorator actively participating on the commission. In the case of Marble House (1892) in Newport, RI, the former William K. Vanderbilt villa designed by Hunt, the floorplan office notations mention five names responsible for some aspect of the execution of specific interiors—Allard, Cuel, Hamel, Pregaldini and Vernon.1 The first four citations refer to Paris based artisans while the last is in reference to the local Newport-based retailer-cabinetmaker-decorator George E. Vernon & Co. The firm of Vernon & Co. (active 1878-1967) was located on John Street in the historic heart of town and provided a host of services to the summer cottage colony from opening and closing of houses, luxury retail furnishings, cabinetmaking to restoration work and interior design.2 The French firms cited at Marble House appear, however, to have worked not independently but as subcontractors for Jules Allard (1832-1907), Paris director of the decorating house of Allard et ses fils with a New York branch office known as Allard & Sons. A reporter from Frank Leslie’s Weekly noted “All of the decorative work is being done by Frenchmen—the real imported article at that. Allard & Sons … who employ nobody but Frenchmen, are doing the color decorations, the hangings, tapestry and furnishings, while about thirty Frenchmen imported expressly for the purpose … are doing the plastic and carving work.”3 Cuel is listed in commercial directories of this period as an upholsterer as is Pregaldini, while Hamel was a stuccoist.

The curious distinction of Frederick Vanderbilt’s country residence at Hyde Park is that at least four fully fledged decorating firms were independently and simultaneously at work on the design and execution of Vanderbilt’s interiors under the general supervision of McKim and the clients. The firms were those of Ogden Codman, A. H. Davenport, Georges Glaenzer, and Herter Brothers. A further distinction is the rare overall carte blanche seemingly given chief architect Charles Follen McKim on the design and furnishing of the ground floor reception rooms. Following an on-site conversation with McKim, Mr. Vanderbilt wrote the firm placing the sum of $50,000 at the disposal of Stanford White, excluding duty and freight charges, to spend on articles of furniture, preferably “old Italian,” and architectural salvage during an upcoming trip to Europe.4 The resultant wish list drawn up by McKim to guide White’s acquisitions is a rare illustration of the architect’s aesthetic just as it would prove to be, in the field, a reflection of White’s effective decorating eye. Furnishing plans are provided for the hall, staircase, reception room, lobbies, dining room, living room and porticoes. In execution, the concept was followed with remarkable diligence. Herter Brothers would carry out the architectural decoration of the entrance vestibule, the elliptical hall and the dining room and A. H. Davenport, the living room.

The balance of the ground floor was consigned to the French-born New York furniture dealer-decorator Georges A. Glaenzer of 33 East 20th Street in New York with a Paris office at 17, rue Caumartin. New York City commercial directories list Glaenzer as a cabinetmaker and by 1886 as a decorator. In contemporary French commercial directories of the 1890s, Glaenzer’s trade, however, is listed as ameublement (furnishings) rather than décoration and the frequency of his applied label on furniture by Sormani, Linke and Zwiener suggests he was primarily a retailer of luxury Paris furniture to the American market.5 The Hyde Park reception room is fitted out with a cabaret table attributed to Linke and a console, clock and bonheur du jour lady’s desk all by Sormani. White had been charged with scouting an “old room in Paris, Style Louis XVI” for the reception room and surely could have procured one from Allard, which seems to imply that Mr. or Mrs. Vanderbilt had, from the start, perhaps intended this space for Glaenzer’s attention. Glaenzer’s role at Hyde Park is almost unique amongst Vanderbilt residential commissions.6 Renderings supplied by his firm suggest an active role in the room’s design but it’s elaboration and execution remain somewhat of a mystery. In gilding and assemblage, the Louis XV style oak paneling with stucco ornamentation is late nineteenth-century French, but the identity of the maker is, at present, unknown.

Glaenzer was also placed in charge of the lobby and den off the central elliptical hall. A curious melange of English Aesthetic Movement at the cusp of Art Nouveau, the two adjoining rooms have a Germanic quality to them that is a seeming departure from the high style academically restrained theme of the ground floor. Again, it is not certain that Glaenzer maintained a woodworking studio of scale to carry out his designs and thus the authorship of the carved mahogany paneling and plasterwork for both small rooms merits further research. A conjectural possibility is that the architectural interiors and possibly the architectural furnishings of these two rooms were produced by A. H. Davenport.

Glaenzer’s final contribution to the Frederick Vanderbilts’ residence was Mr. Vanderbilt’s bedroom on the second floor. Although later slightly modified by the Herter Brothers, the bedroom as designed by Glaenzer may be related to interiors of the same decade executed by Davenport for his frequent collaborator, the architect Robert Swain Peabody of Peabody & Stearns, Boston. In Peabody & Stearns’ 1895 Beechbound at Newport, RI, the summer estate of William Fletcher Burden Jr. (1856-1897), a Renaissance style dining room features wainscoting with fitted Verdure tapestry wall hangings installed by Davenport and not unlike the scheme intended by Glaenzer for Frederick Vanderbilt’s room. In addition, it is highly likely that Davenport executed the Medieval-Renaissance style baronial interiors of Frederick’s 1891 Peabody & Stearns-designed Rough Point in Newport.7 This prior association may have encouraged such teamwork in Mr. Vanderbilt’s mind, placing Davenport at Glaenzer’s disposal as a sub-contractor. In fact, much of the French classical bedroom furniture in Hyde Park, thought to have been supplied by Glaenzer, might be from A.H. Davenport rather than French sources. The suites bear close resemblance to the Davenport-supplied French Louis XV and Louis XVI style bedroom suites ordered by Ogden Codman for Cornelius Vanderbilt, II’s The Breakers (1895) in Newport and now known to have been primarily manufactured by Davenport.8

There appears to have been an enduring reluctance on the part of Frederick and Louise Vanderbilt to use the services of Jules Allard and Allard & Sons on their later building projects, despite Louise’s reported love of all things French. The firm had been closely associated with, and indeed helped define, Vanderbilt taste since 1878. It may be due to the fallout of the Allard Customs Swindle of 1888, in which Frederick was listed in the press as a leading client. The publicity sullied the firm’s name and led to a patriotic preference for domestic artisans. Or perhaps the Frederick Vanderbilts had the simple desire to distance themselves from the aesthetic of other members of the family. Whatever the case, Allard was nonetheless present in Frederick’s life at this point, for he was responsible for the design and execution of the Louis XIV and Louis XV interiors of the Vanderbilts’ steam yacht Warrior and in a minor way for touches at Hyde Park. Here, Allard provided the Louis XV bureau a cylindre for the living room (possibly moved from the city residence at 459 Fifth Avenue), consulted on the second floor light well and adapted two large “Italian” tables bought abroad by White (one from Stefano Bardini, Florence).9 One of these modified tables is likely the center table of the elliptical hall.

This leaves us with the services rendered by Ogden Codman (1863-1951), fresh from his completion of the second and third floor family apartments at The Breakers for Frederick’s elder brother Cornelius and the 1897 publication, with Edith Wharton, of his influential opus The Decoration of Houses. Based on Codman’s personal observations of European precedents, architectural platebooks and treatises and art historical study, the young architect-decorator’s manifest signature became academic design purity and stylistic unity. In his design therefore for Mrs. Vanderbilt’s bedroom and boudoir at Hyde Park, one would fully expect an archaeologically correct citation, with modern conveniences for circulation, comfort, light and storage. The choice of a Louis XV prototype would have been assumed, as contemporary tastemakers found the Rococo the softer, more feminine style appropriate for ladies’ chambers. It was also not uncommon for such period-inspired private rooms, given the ambitious physical scale and historical aspirations of American plutocratic architectural interiors of the age, to replicate the state bedrooms or chambres de parade of European sovereigns.

Indeed Mrs. Vanderbilt’s bedroom, as realized, has, in its design vocabulary, all the bells and whistles of a theoretical French royal bedroom. The canopied state bed, raised on a dais against a wall and separated from the rest of the room by a partition of raised columns with curvilinear balustrade, echoes the public ceremonial function of a state bedroom. The King’s getting-up and going-to-bed ceremonies could attract around one hundred spectators, with the central stage being the balustraded bed enclosure, separating the royal personage from the less privileged public assembly. The King would officially rise, for example, at eight thirty in the morning following a wake-up call from the first Valet de Chambre; a visit from the First Doctor and First Surgeon and the Royal Chaplain would follow; members of the royal entourage would be next to enter the room while the King was washed, combed and shaved publicly; Officers of the Royal Chamber and of the Clothes Storehouse would then arrive for the grand lever ceremony during which the sovereign was dressed and drank soup for breakfast, attended by a steadily growing number, at each stage, of family, ministers and courtiers. The ceremony would be repeated in reverse at eleven thirty in the evening.

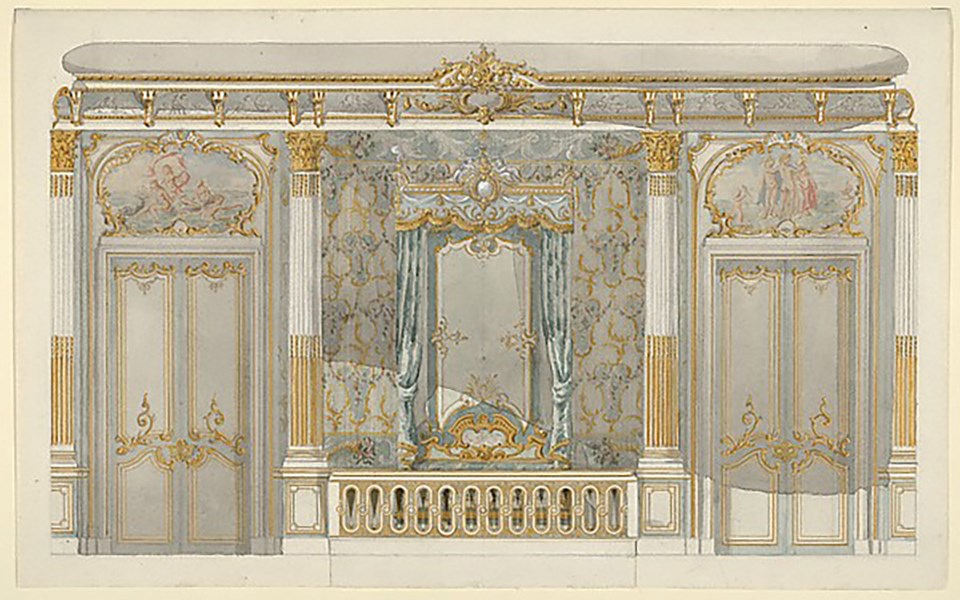

In design, however, the room does not attempt to specifically recreate the King or Queen’s State Bed Chambers at Versailles. Like Glaenzer’s paneling, or boiseries, the full length oak walls panels are distinctly nineteenth century French in origin. Each lateral panel is painted a pale grey, known in the nineteenth century as gris Trianon, with gilded ornament picked out in bronze powder gilding simulating or vieilli; inset painted panels in the spirit of Boucher, and provided by Duveen Brothers, crown each wall panel and mirror. As Codman’s renderings for the project survive in the Avery Library and at the Metropolitan Museum, it is possible to make certain deductions concerning the designer’s source of inspiration (Fig. 1). It is rather apparent that there was no existing built prototype for Louise Vanderbilt’s bedroom nor is its design an amalgam of selected Louis XV period bedchambers surviving in France.

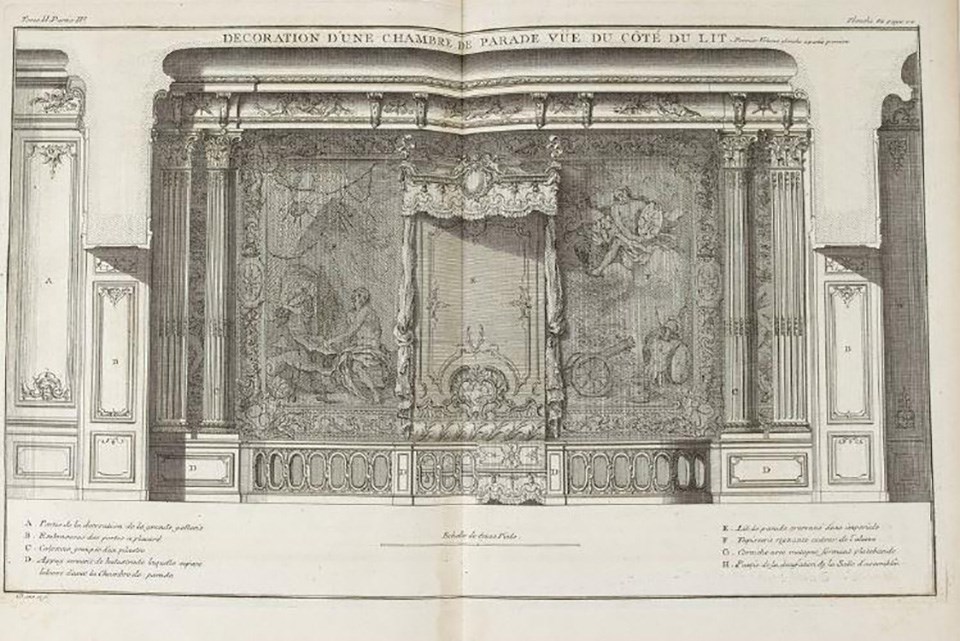

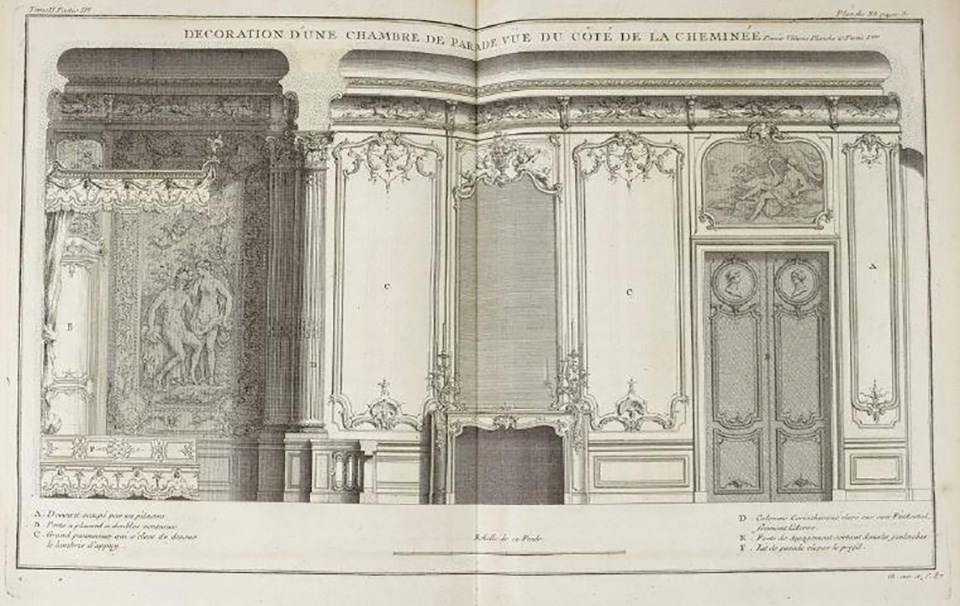

Perhaps, following Codman’s methodology, the first place therefore to seek a parallel might be in consulting one of the influential eighteenth century architectural platebooks. Indeed in the second volume of Jacques-François Blondel’s 1738 De la distribution des maisons de plaisance et de la décoration des édifices en général, page 210, plate 82 (no. 1) depicts a state bedroom with canopied bed, set behind a Corinthian column-flanked balustrade. In design, the columns, balustrade, cornice and headboard of the elevational plate are an enticingly close match to Codman’s design for Mrs. Vanderbilt.10 A further plate, 82 (no.2), shows the projection of the state bed alcove into the bed chamber with the large, lightly decorated, Rococo paneled decoration of a flanking mirrored chimney wall replete with double door and a cartouche-shaped overdoor painting. This scheme logically would have provided just the academic rectitude desired by Codman for the balance of the bedroom’s layout but was never literally adopted.

It is probable that plate 82 of Blondel is ultimately the original design source but with major intermediate revisions. Were these revisions Ogden Codman’s or might they have been the vision of a third party? Was the decorator looking at an altogether different source playing on Blondel? During the nineteenth century, a number of French architects published highly influential platebooks on architectural decoration led by César Daly and Eugene Viollet-le-Duc. Such authoritative and comprehensive works today overshadow the contribution of lesser design theorists who published anthologies of designs for furniture, decorations and upholstery. Amongst the latter was Alexandre Eugene Prignot (1822-1895?), remembered primarily for his commercial role as a furniture designer for the leading English firm of Jackson & Graham. Yet, in his day, Prignot was cited as a standard reference; at the 1888 Watson sale in New York, the auction of the library included “technical books that are the standard works of Chippendale, Sheraton, Hepplewhite, Ince and Mayhew, Chambers, Standage, Richardson, Prignot and Pergolesi.”11 Prignot was trained in the Paris workshop of Henri Auguste Fourdinois (1830-1907), a frequent medal winner known for monumental historicist furniture shown at the International Exhibitions of the day. He then worked in London from 1848 to 1855 for Jackson & Graham and designed their entry for the Paris International Exhibition of 1855, a Louis XIV style porcelain plaque-adorned cabinet with mirror that won considerable acclaim for the English at the Exhibition.12 Returning to France, Prignot published anthologies of his designs for furniture, decorations and upholstery, that became widely disseminated amongst contemporary decorators, including the Paris house of Jules Allard. In 1867 Alexandre Prignot was awarded a gold medal for design at the Paris Universal Exposition. Between 1869 and 1873 Prignot assembled a working proof copy of 136 interior design plates under the heading L’architecture, la décoration, l’ameublement, this manuscript would be edited and published, under the same title, by Claessen, Paris with 60 photographic plate reproductions of his drawings in 1873 and 1879 editions. The larger original proof copy of this work, owned by Prignot, is now in the collections of the Cooper-Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum Library in New York.13

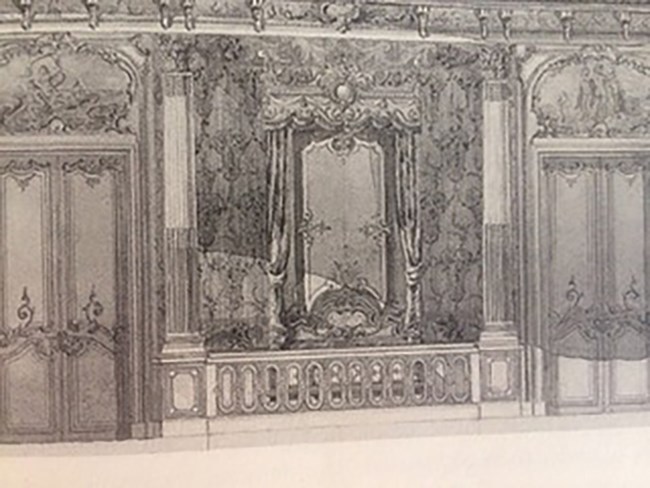

In the Cooper Hewitt’s original Prignot copy, plate 14, with the caption “chambre a coucher,” is what appears to be the final design source for Codman’s conception of Louise Vanderbilt’s bedroom at Hyde Park.14 The fidelity with which Ogden Codman reproduced Prignot’s design is remarkable. The Louis XV-style bed chamber alcove bed headboard, appliquéd bed hangings and coverlet, wall paneling, doors, overdoor painted cartouches, cornice, raised columns, balustrade and even the pattern of the woven wall fabric are faithfully repeated. The Prignot plate differs from Blondel in the placement of the doors, swinging central gate of the balustrade, paneling design and wall hanging, but its design affinity remains clearly apparent.

Cooper-Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum Library

Plate 15, curiously appearing under the same number in both the original proof compilation and the later Claessen editions, is captioned “commode Louis XV” and shows a Louis XV style commode or chest of drawers placed in front of a wall mirror, flanked with Rococo wall sconces, set into Louis XV-inspired wall paneling and flanked by doors with cartouche-shaped overdoors. With the exception of the mirror crest rail decoration and the position of the doors, this companion plate to no. 14 is the inspiration for the adjoining walls of Mrs. Vanderbilt’s bedroom. The placement of a pair of mahogany and gilt bronze commodes in front of a painted Rococo style wall bay goes against period precedent. In Blondel, a console whose lines echo the contours of the wall ornamentation, would have been the norm, placed in position as an anchored architectural piece of furniture or meublant. But in referencing Prignot, Codman found a new alternate precedent although the commodes he actually used on site, in front of the mirrors at Hyde Park, are of a different scale than those illustrated in his rendering. Possibly from the then existing Vanderbilt collection, they are slightly too large for their setting and do not conform to the mirror bay as well as in Prignot’s design.

Might the selection of Prignot as a respectable design reference have been purely Ogden Codman’s choice or might it have been suggested by Louise Vanderbilt? Evidence indicates that members of the Vanderbilt family frequently consulted the design books of Henry Havard, present in their libraries, and in communication with their decorators, such as Allard, referenced specific plate numbers as suggested design sources.15 This could have been the case at Hyde Park if a copy of Prignot happened to be in Frederick’s library and if the original copy’s plate 14 appeared in the subsequent editions, which it did not. An alternate scenario lies in the fact that Eugene Prignot had some form of association with the Paris firm of Jules Allard. Prignot suggested that his son Robert Prignot (d.1888), being conversant in English from his father’s sojourn in London, enter into a partnership with Jules as his American representative following the resounding success of the Vanderbilt commissions between 1878 and 1883. By 1883, Robert was in New York operating as the representative of a new firm named Allard & Sons & Prignot and remained in this position until December 1887.16 He was recalled at the end of that year, suffered a mental collapse and died in Paris in 1888. During Robert Prignot’s short New York interval, his father’s draft copy may have ended up in the New York branch office’s library.

It could therefore be possible that Frederick Vanderbilt had dealt previously with Robert Prignot on earlier business with Allard for either art acquisitions or commissions. It could also be that Ogden Codman had some acquaintance with Robert from the design world. Although Eugene Prignot’s design books were widely known, stylistically they were so redolent of French Second Empire taste that they may have been considerably dated by the late 1880s and early 1890s. If, however, we allow for some potential personal contact with Robert Prignot, then such contact might help further explain the familiarity with and use of Eugene Prignot’s limited circulation designs. In the end, Hyde Park’s interiors go far in illustrating collaborative practices amongst Gilded Age architects, clients and artisans and teach us to look not just to the anticipated classic reference books but to also take into account lesser known, fashionable design anthologies of the era.

By Paul F. Miller, December 2019

Notes

1 Richard Morris Hunt Papers, Library of Congress AIA/AAF Collection, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

2 Vernon did upholstery work for the Vanderbilts at Hyde Park and some furnishings by his shop were moved there following the sale of the Newport cottage Rough Point.

3 Newport Mercury, February 27, 1892, p.8.

4 Memorandum of September 17, 1897, Stanford White Papers, Box 19:2, Avery Architectural Library, Columbia University.

5 A Boulle-inspired walnut cabinet by the Paris furniture maker Julius Zwiener (1867-1922) bearing the retail label of Glaenzer was formerly in the collection of James B. Duke at Rough Point, Newport or 1 East 78th Street, New York. If not acquired for New York, it may have been conveyed with the purchase of Rough Point from Princess Anastasia of Greece (Nancy Leeds) and date from the Frederick Vanderbilt era. The cabinet was donated to the Preservation Society of Newport County by Miss Doris Duke and is now in the collection at The Elms.

6 In 1892 George W. Vanderbilt had hired Glaenzer to design the Vanderbilt Gallery of the Fine Arts Society Building on 58th Street in New York.

7 Peabody & Stearns papers and renderings are in the collections of the Boston Public Library.

8 Archival notes by Gladys Vanderbilt Szechenyi on The Breakers construction, now on deposit at the Newport Historical Society, reference Davenport as a supplier for the Codman furnishings and Ross & Roach of Boston for woodworking; similarly Vanderbilt invoices for The Breakers survive in the Davenport papers preserved in the collections of Historic New England.

9 Stanford White to Frederick Vanderbilt, letter of account dated May 24th, 1898; with pencil notation “Allard” denoting location. Stanford White Papers, Avery Architectural Library, Columbia University.

10 The bed alcove’s walls in Blondel’s plate are fitted with allegorical tapestries rather than the silk wall fabric at Hyde Park.

11 New York Tribune, Saturday, June 15, 1888, p.2.

12 The cabinet was purchased from the Exhibition by the South Kensington Museum, now the Victoria & Albert Museum, London, and remains in their collections.

13 Call number NK2049.P75; gift, 1982, of Derek Ostergaard.

14 This plate was replaced and omitted from the subsequent published editions.

15 Gladys Vanderbilt Szechenyi papers on the construction of The Breakers, Newport Historical Society.

16 The New York Sun, Saturday, April 6, 1889.