Last updated: August 26, 2020

Article

Hyde Park Farms

The Farm Barns and Clock Tower, Hyde Park Farms. NPS Photo

The

A key element of the American country house movement and of the country place itself was the illusion of an independent landed existence created by farming an estate. Farm groups were typical, if not characteristic, of the country estates built by wealthy Americans during the Gilded Age.1 As the era reached its highest expression in country place design, farm groups often incorporated aesthetic features not typically found among working farms associated with rural residences. In essence, the Vanderbilt farm group and others like it were designed to look like quaint rural villages and performed an important function in the larger country place experience. Hopkins’ farm groups were sometimes thought more interesting than the architecture of the country houses they served. As he noted in 1920, the numerous buildings required for a farming operation were “capable of such an infinite variety of groupings that the requirements of the farm would seem to offer more scope to the architect than do the problems of the house.”2

Hopkins insisted that the various centers of interest on a large estate maintain their individuality. Hopkins writes:

The house place, with its hospitality of garden, lawn or grove; the farmstead; the stabling and garage; the deer park; the lakes or watercourses with their verdured shores—each contributes to the fascination of the whole; but since it is in human nature to become fatigued with what is continually before the view, it is well to give to these various centers a certain seclusion of their own. This would suggest the choosing of a site for the farm barns well away from the immediate haunts of the home, and where they may be visited only by a pilgrimage through pleasant fields and lanes.3

The Hyde Park landscape follows this principle. In addition to its agricultural purpose, the Vanderbilt farm group contributes to the larger estate experience for its architectural interest and as a destination—farm groups were intended to please the eye and highlight the bucolic ideals of a rural setting.

The wealth of the gentleman farmer during the Gilded Age had a sizeable effect upon the development of agricultural methods, experimentation, and architecture. The most enduring symbol of this aspect of the country place era, which was at its peak from about 1890 to the First World War, is the farm group. The architecture of these idyllic structures joined indispensable sanitary and efficient arrangements with a new emphasis on pleasant visual effects. Farm architecture was the focus of as much consideration with regard to planning and appearance of an estate as the primary residence. Mansions were merely the crowning feature of the American country place during the Gilded Age. These large properties required numerous support buildings—gate houses (often more than one), stables and garages, greenhouses, boathouses and docks, pumping stations, power plants, a winter cottage for off-season weekends, guest houses, casinos, kennels, polo stables, a farming complex, and cottages for an army of estate employees. A dozen or more of these structures was not uncommon, and often there were more. Hyde Park had about twenty such buildings, many illustrating the charming possibilities they could provide for the architect. At Hyde Park, the Coach House by Robert Henderson Robertson and the Farm Group by Alfred Hopkins are fine examples of this aspect of the American millionaire’s rural seat.

The farm group was a well-developed, integrated facility that brought together a millionaire’s herd of prized cattle, milking cows, poultry, pigs, and equipment that usually included adjoining housing facilities for the farmhands. The farm of a country place was sometimes referred to as a “gentleman farm” or “hobby farm” because the farm rarely if ever was self-supporting. On the practical side of the matter, healthy food, particularly milk, was difficult to obtain in remote areas, and, even in the city, produce might not always be trusted. While the farm provided for most of the family’s food needs, supplying meat and produce for both country house and town house, they were also breeding clinics for the genteel pastime of raising prize livestock. Although turning a profit was never the intent of the farm, improving livestock and streamlining management did appeal to the good business sense of the American capitalist. Challenged by the competitive element of farming, the American millionaire’s recreation included such activities as improvement in production and efficiency, as well as experiment and innovation.4 These men frequently gathered at the New York Farmers’ Club, an organization that included men of wealth and position who met regularly to discuss best practices and advances in agriculture, particularly those related to the management of their own hobby farms. Jocularly referring to themselves as the “Fifth Avenue farmers,” impressive men such as J.P. Morgan, William K. Vanderbilt, William Dinsmore, Joseph Choate, Elbridge T Gerry, Ogden Mills, Levi P. Morton, Archibald Rogers, W.D. Sloan, William Rockefeller, W. Seward Webb, and George B. Post gathered regularly to discuss such topics as pigs, hay, and weeds.

The farm group also represents the country house owner’s role in a national movement of profound nostalgia for the country’s agrarian past. Since the Civil War, and particularly during the rising industrialization of the country at the turn of the century, the nation’s agricultural economy was experiencing an epic decline. The eminent writer John Burroughs, whose own retreat was across the Hudson River in the Catskills, noted in his writings the “common complaint that the farm and farm life are not appreciated by our people.”5 Nostalgia for country life and the nation’s agrarian roots culminated in a “back to the land” movement that embraced all levels of society, particularly the wealthy who had the means to migrate toward the open country. “We would preach the sermon of the out of doors, where men are free. We would lead the way to the place where there is room, and where there are sweet, fresh winds....We shall endeavor to portray the artists in rural life,” announced the editor of Country Life in America.6 Alfred Hopkins placed the farm group firmly in this tradition when he wrote:

With these buildings in effective combination and appropriately placed among the fields, the picture of the farm can be made so pleasing, and the idea of going back to Nature as the source of all sustenance so ingratiating, that it would be possible to build up an effective philosophy on the principle that the architecture of the home should be made to resemble the architecture of the farm, rather than the other way about.7

The Diary, Hyde Park Farms. NPS Photo.

The tremendous burst in growth of properties like Hyde Park during the Gilded Age paved the way for architectural specialization in the more complex estate structures. Alfred Hopkins (1870-1941) was the unquestioned dean of farm architecture. Born in Saratoga Springs, New York in 1870, Hopkins was trained at the prestigious Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris. By 1902, when he published his article on “Farm Barns” in the Architectural Review, his reputation for farm design was firmly established. His largest body of work was probably concentrated in New York with about fifteen commissions on Long Island, and fewer known examples scattered along the Hudson River. Other commissions are known to be as far away as the Lake Forest District of Chicago, and possibly the Adirondack region of upstate New York. In 1913, Hopkins published the definitive treatise on the subject, Modern Farm Buildings, which went into three additional editions by 1920. The full extent of Hopkins’ work may never be known. His success was due in part to his ability to work well with other architects—McKim, Mead & White, Bertram Goodhue, Trowbridge and Livingston, John Russell Pope, Horace Trumbauer, Charles Platt, Cass Gilbert, and others. Farm Groups attributed to these architects may actually be the work of Hopkins.

Hopkins’ partnership with Edward Burnett (1849-1925) also brought his work to the attention of a host of potential clients. Burnett was the son of a chemist who made a fortune in flavored extracts and established a model farm on the family’s rural seat in Southborough, Massachusetts called Deerfoot. After completing his studies at Harvard in 1871, Edward devoted the next fifteen years to managing Deerfoot and very quickly transformed it from a model farm into a commercial operation employing more than five hundred workers. At Deerfoot Farm, Burnett demonstrated advanced agricultural practices, innovations in hygiene, experimentation with feeds, was an early importer of fine breeds of cattle, and a pioneer in breeding stronger American stock weakened by decades of inbreeding. His success attracted national attention. Burnett’s stature in scientific agriculture is compared to that of Gifford Pinchot’s in forestry.

As a successful businessman and large employer, Burnett entered the United States House of Representatives in 1886 and served as an active member of the House Committee on Agriculture. Unsuccessful in his bid for re-election, Burnett returned to private life and initiated the second phase of his agricultural career. A self-proclaimed “farm expert,” Burnett established himself as a professional developer of private farming operations for the country seats of wealthy Americans. Burnett’s background, expertise, and reputation in managing a large-scale farm aided his amateur clients in developing their own farming operations, utilizing the most up-to-date practices and technologies. Burnett was responsible for purchasing livestock for the farms, often placing an order for several farms at once in an effort to get a better price. Burnett also frequently served as the farm manager for these impressive agricultural operations. From 1889 to 1892, Burnett was planner, purchasing agent, and head of the Agricultural Department at George Vanderbilt’s Biltmore. In 1892, Burnett began serving as designer and general manager of Florham Farms in Madison, New Jersey. Florham was the country place of George and Frederick Vanderbilt’s brother-in-law, Hamilton McKown Twombly. Sometime around 1900, Burnett began designing the new farm at Hyde Park, and for the first year or so after its completion, managed the operation until Herbert Shears, Hyde Park’s superintendent, assumed the management of the farm.8

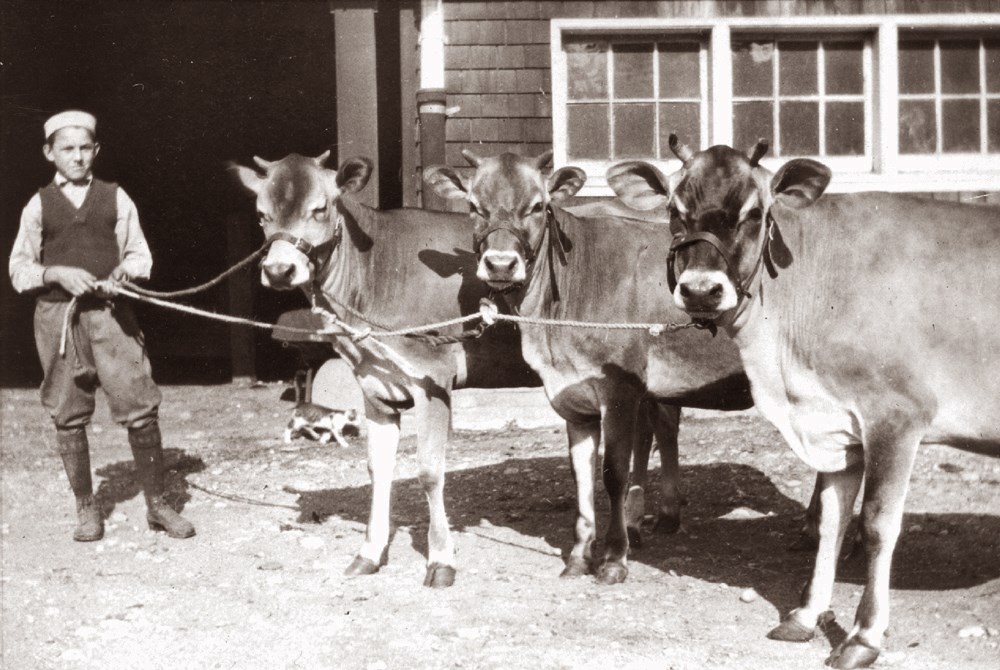

A farm worker with three of Vanderbilt's Jersey cows. NPS Photo.

History of the Hyde Park Farm Group

Vanderbilt purchased Hyde Park in 1895. The 600-acre property during Vanderbilt’s ownership included a stately mansion designed by McKim, Mead & White, numerous support structures, formal gardens with extensive greenhouses, a landscaped park, and a working farm complex surrounded by pasturelands and natural woodlands.

An older set of farm buildings stood on the site of the present farm group when Vanderbilt purchased Hyde Park in 1895. The location of these structures appears on an 1895 survey map of the property prepared for Frederick Vanderbilt at the time of his purchase. The older buildings were in a state of extreme decay, and Vanderbilt made some structural repairs in 1898. McKim, Mead & White billed Vanderbilt $42,377 for work related to “barn, cottages, miscellaneous outbuildings.”9 This work predates the 1901 construction of the new farm and probably refers to the structural repairs carried out by E. S. Foster in 1898.10

In June 1901, Vanderbilt entered a contract with Cregan and Collins, a building firm from Morristown, New Jersey, to replace some of the existing buildings and construct new ones, primarily the Superintendent’s Cottage, the Barn Complex, a Dairy, and a poultry house.11 An article by Alfred Hopkins on farm groups published in the Architectural Record in 1915 identifies Edward Burnett as “expert” and Hopkins as architect for the Hyde Park farm group.

The plan and many details of the Hyde Park farm buildings represent the Hopkins tradition. The attribution is further supported by several references to a “Mr. Hopkins” in Herbert Shears’ journals (Superintendent of Mr. Vanderbilt’s Hyde Park estate). On 17 September 1901, Mr. Shears “met Mr. Hopkins at train and showed him around the new barns,” and on 25 April 1902, Shears noted “Mr. Hopkins up to take pictures of barns.” On another occasion, this Mr. Hopkins delivered plans for the new hen houses.12 Mr. Shears’ journals also make frequent reference to Edward Burnett during the early years.

The Vanderbilt farm maintained pure-bred Jersey cattle for dairy production, Belgian draft horses for farm work and breeding, poultry, vegetable gardens with dedicated greenhouses (ornamental greenhouses were adjacent to the formal gardens on the park side of the estate), a 20-acre orchard, and a dairy for processing milk and butter. Many of these features are visible in a 1936 aerial photograph of the estate.

The Poultry House at Hyde Park Farms. NPS Photo.

Hopkins farm groups were typically built with a low orientation to emphasize its rural character. At Hyde Park, for example, the roof pitches are low, the massing heavy in places visually weighing the structure toward the ground. Buildings with separate dedicated functions are joined by loggias or passageways, and although quite attractive, are characteristically simple and without architectural ornament. Hopkins insisted that farm buildings be both practical and artistic. The rustic materials used in the construction of the Hyde Park farm group contribute much to its aesthetic charm. The architectural character of Hopkins’ farm groups is distinctive—often possessing the appearance of a quaint village. An added feature to the functional purpose is the emphasis on aesthetic appearance.

The Hyde Park barn complex is built in the shingle style with field stone masonry. Hopkins recommended that nothing was more fitting for farm architecture than the combination of rough field stone, hewn timbers, and rived cypress shingles.13 The elegant simplicity that governs the design and the reticence in the use of ornament is characteristic of

At

The

Dutchess County Horticultural Society outing at Vanderbilt's Hyde Park Farms, 1908. NPS Photo.

After Frederick Vanderbilt’s death in 1938, the entire estate was offered to the National Park Service through the personal involvement of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Neither the U.S. Congress nor the National Park Service supported the acquisition of Hyde Park with much enthusiasm. It was reluctantly accepted, and although the entire estate was offered, the farm complex and its surrounding 438 acres were not included as part of the congressional designation. Almost immediately, however, operational concerns surfaced, particularly with regard to traffic, parking, and circulation, and park officials considered pursuing additional land acquisition from the farm side of the old estate, but without results.

Elmer Van Wagner, Sr. purchased the 438-acre farm tract from Mrs. Van Alen in 1942. Again, President Roosevelt initiated the transaction to prevent the development of a proposed county jail on the site. Van Wager leased the barns to an individual who operated a public stable. In 1952, Van Wagner sold the farm complex to Richard Harrity who converted the Hay Barn into a theater, but never hosted performances. The following year, the barns were purchased by Hillary Masters, son of the poet Edgar Lee Masters. Hillary’s wife Polly founded the Hyde Park Festival Theatre, and the title to the property was transferred several times over the following years. The property was sold again in 1978 to William “Biff” and Jeannie McGuire, professional television and stage actors, who continued operation of the theater. Today, the farm structures and associated lands remain in private ownership.

By Frank Futral, Curator, Roosevelt-Vanderbilt National Historic Sites

Notes

1 Farm group was the term typically used in the United States during this period. In England, the preferred term was “model farm.”

2 Alfred Hopkins, Modern Farm Buildings (New York: McBride, Nast, & Company, 1913), p. 16.

3 Modern Farm Buildings, 17.

4 Clive Aslet, The American Country House (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990), 136.

5 Quoted in Aslet, 138.

6 “What This Magazine Stands For,” editorial, Country Life in America I (November 1901-April 1902): 24-25.

7 Alfred Hopkins, Modern Farm Buildings (New York: McBride, Nast, & Company, 1913), 16.

8 Harry T. Briggs notes in his memoirs that Mr. Vanderbilt engaged Edward Burnett to manage the farm, which had been in an unsettled state of affairs, and untangle a mess of disorganization, inefficiency, and drunkenness. Harry Tallmadge Briggs, Reminiscence: The Memoir of Harry Tallmadge Briggs, (New York: Town of Hyde Park Historical Society, 2004), 90. See also references in the Hyde Park estate account books.

9 Leland M. Roth, The Architecture of McKim, Mead & Whtie, 1870-1920, A Building List (New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1978), 156.

10 National Register Nomination, section 8, page 2.

11 National Register Nomination, section 8, page 2.

12 See Pocket Journals of Herbert Shears, entries for 17 September 1901, 25 April 1902, and 28 September 1901. Vanderbilt Mansion National Historic Site.

13 Hopkins, 18.