Last updated: October 10, 2020

Article

Husking Parties in Concord, Massachusetts

Public Domain, Courtesy of the MFA Boston

“The season was cheerful, the weather was bright,

when a number assembled to frolic all night.” - Jacob Baily, Loyalist Poet

Husking Parties

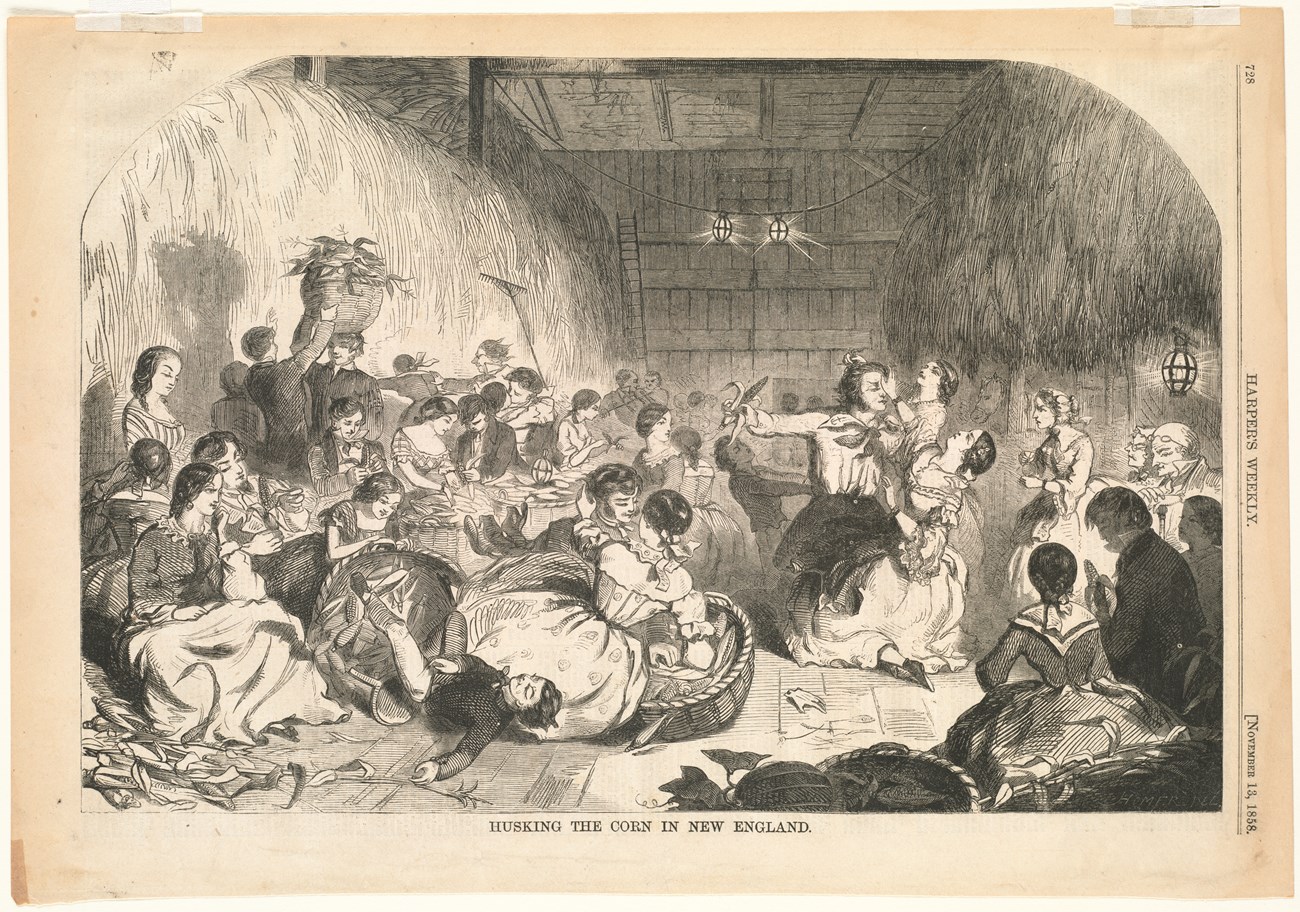

Although Halloween was not celebrated near Concord, Massachusetts until late in the 19th century, the locals did have festivities referred to as “husking parties,” and “frolics.”

At their core, husking parties were an important activity meant to prepare food for the winter. After the annual harvest, local farmers needed to ready their corn for storage by removing the silky husk that trapped moisture and caused rotting. This process called, “husking,” ensured the families survival through a harsh winter.

According to one local writer, families spent weeks preparing for a husking frolic. The house was cleaned, food prepared, and “The cider barrel had been ‘hossed up’ in the dooryard, beside a bountiful pile of ‘eating apples.’”1. In 1828, Concord citizen John Neil wrote an article titled, “A Husking As It Is.” In his work, Neil claimed,

“When one of our thrifty New England farmers intends to have a husking, he picks his corn from the hill, or cuts it up by the roots and hauls it too, and piles it up in one end of his barn for two or three days previous to the appointed night; the day preceding the husking he sends a boy round within the circumference of a mile perhaps, with particular and general invitations… The boy who bares the invitation sometimes carries the empty jugs about with him, as a sort of bait, or to let them know that white-eye [New Rum] will be there.” 2.

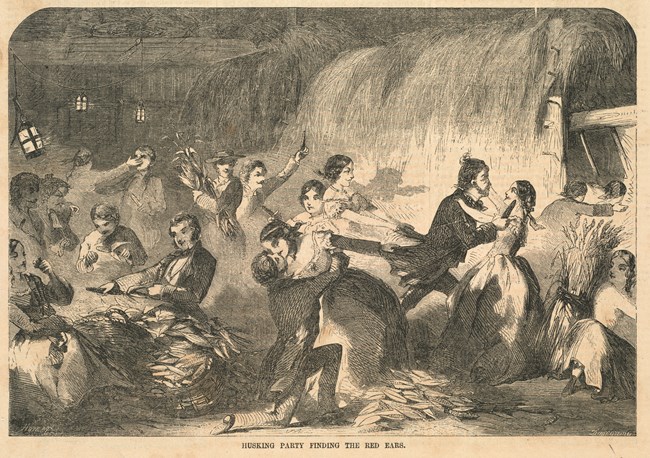

Homer, Winslow. "Husking party finding the red ears." Print. November 28, 1857. Digital Commonwealth, https://ark.digitalcommonwealth.org/ark:/50959/sn00b689g (accessed October 09, 2020).

In some areas local tradition held that finding a red ear of corn was good luck, deserving of a prize. Red ears of corn were an infrequent discovery, caused by an imbalance of sugar in the plant. The rarity of these red ears inspired local folklore. Some early accounts of husking frolics, held that the individual who found a red ear received a kiss as a reward. For the young romantics in a husking party, finding the red ear became a highly coveted tradition. In later accounts, finding the ear caused the entire party to chase the finder until the ear was forfeited via capture.6.

According to John Neil in 1828, “Thus passes away the evening till toward the close: when the word is ‘lets see who’ll have the last ear first! Then it is ‘neck or nothing,’ everything is pell-mell, helter-skelter, pig corn, baskets and all are upside down; or as they have it, they ‘turn up jack.” 7. With the sun setting, attention then turned to the frolic or party.

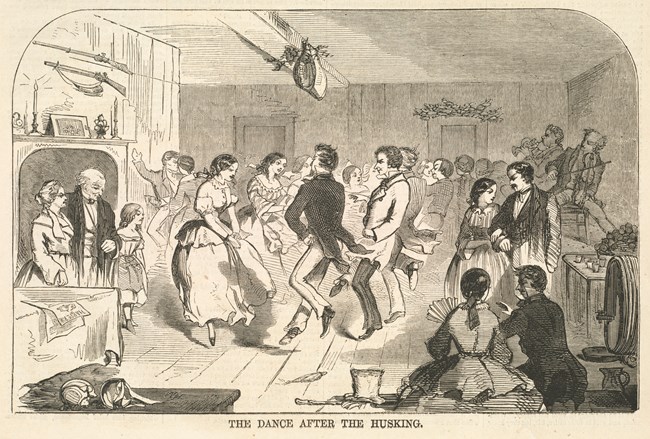

Homer, Winslow. "The dance after the husking." Print. November 13, 1858. Digital Commonwealth, https://ark.digitalcommonwealth.org/ark:/50959/r494vn453 (accessed October 09, 2020).

The Frolic

Traditionally, after husking a large supper was set, and “…they all repair to the house, or the refreshment is brought out to them, where a motherly quantity of lusty pumpkin and coalpit or two-story apple platter pies are provided, with a fresh new skimm’d milk cheese (green) and hot biscuit. Oh what a luxury! Every one eats his fill, and washes down with good old orchard, or hop beer…” In the late 18th century, Loyalist Poet Jacob Baily wrote of one Frolic dinner,

“The girls in a huddle stand snickering by

Till Jenny and Kate have fingered the pie.

Then on it like harpies with hunger they fall,

Or rather like scholars in old Harvard Hall.”8.

After dinner festivities carried on long into the night as the young people were left “…to engage in games, and the elders, grouped about the sitting room fire, talked of olden times…” In many instances, dark stories of witchcraft and the devil’s minions enthralled participants. Local writer Alfred Hudson recalled the listeners drawn in toward their storytellers, “…least they miss something, [as] they only expressed the common avidity for grewsome subjects.” 9.

Fortune telling was another popular tradition of frolics and husking parties. When young romantic sentiments took hold, fortune telling promised to reveal future lovers. Practices ranged from roasting nuts over a fire, looking down wells to see the face of a future spouse, and throwing balls of yarn in hopes their soul mate would follow it. Other games included “Button—roll the plate—chase the lady”, “wrestle, scuffle, jump, heels overhead, pull sticks, throw corn, &c, &c.” 10.

Homer, Winslow. "Husking the corn in New England." Print. November 13, 1858. Digital Commonwealth, https://ark.digitalcommonwealth.org/ark:/50959/r494vn410 (accessed October 09, 2020).

"Scenes of Vile Lewdness"

When on their own the younger romantics danced, sang, and frolicked together in ways that future generations referred to as “scenes of vile lewdness.”11. John Neil in Concord warned of the many “romping plays,” where “they kiss,” and sometimes, “sit on each others knees, or lap.”12. In the late 18th century, famed loyalist poet Jacob Baily described a frolic scene,

“The chairs in wild order flew quite round the room:

Some threatened with firebrands, some brandished a broom,

While others, resolved to increase the uproar,

Lay tussling the girls in wide heaps on the floor.

Quite sick of confusion, dear Dolly and I

Retired from the hubbub new pleasures to try.”13.

After hours of music, games, food, and drinking the festivities came to an end. “Rain or shine,” participants headed home, likely thinking over the spooky tales of haunting devils lurking in the dark, or their romantic interests left by the fireside.

Conclusions:

For generations, husking parties and autumn frolics remained a staple of New England tradition. In the early 19h century, an era of socially conservative values, the grand children of the revolutionary period shifted towards temperance, modesty, and proper etiquette. By 1828, John Neil in Concord recorded, that “it is no more the fashion for females to go a husking in the country…though it undoubtedly has been in days of yore.”14 Fortunately, these restrictive conditions did not last and by the mid-19th century frolics and husking emerged again as a tradition for all.Over time, those practices mingled with the cultural rituals flowing into America via waves of immigration. When Scottish and Irish immigrants brought holidays such as All Hollow’s eve, they mixed with other forms of traditional folklore to create a uniquely American experience. Today, many aspects of husking parties are still present within our own Halloween traditions.

Bibliography;

Baker, Ray Palmer. "The Poetry of Jacob baily, Loyalist." The New Englander Quarterly 2, no. 1 (1929): 58-92.Hudson, Alfred Sereno, The History of Concord, Massachusetts, (Concord, Ma: The Erudite Press, 1904)

Neil, John, "A Husking As It Is" Yeoman's Gazette, Concord, Ma, 11.15.1828

Notes:

1 Hudson, 1902 Neil

3 Ibid.

4 Hudson 191

5 Neil

6 Hudson, 190

7 Neil

8 Neil; Palmer 68-69.

9 Hudson 191

10 Neil

11 Jacob Baily

12 Neil

13 Palmer, 69.

14 Neil